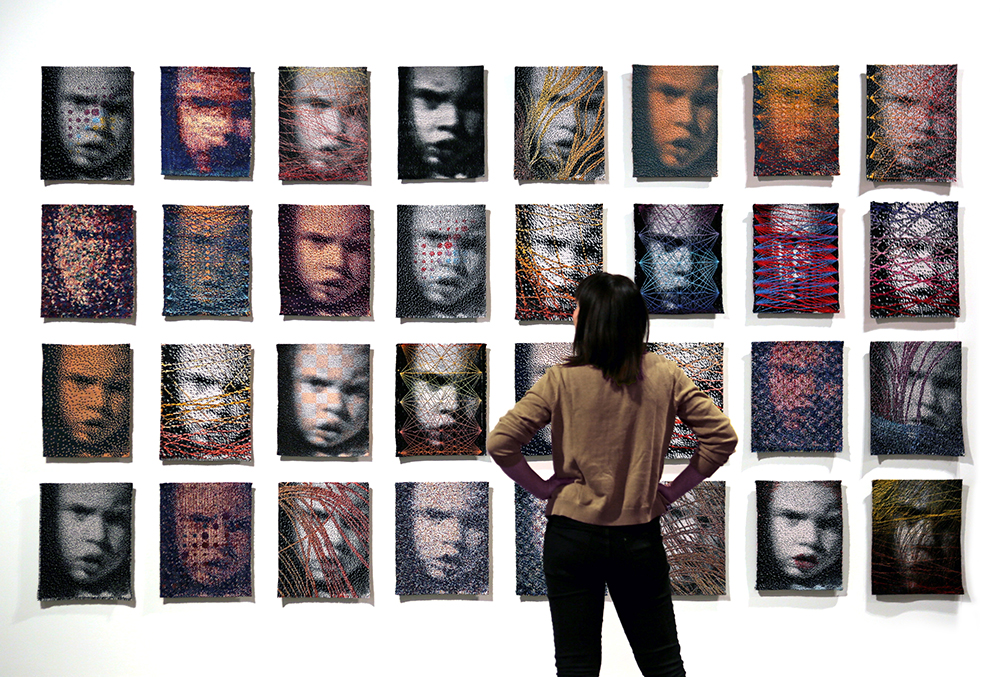

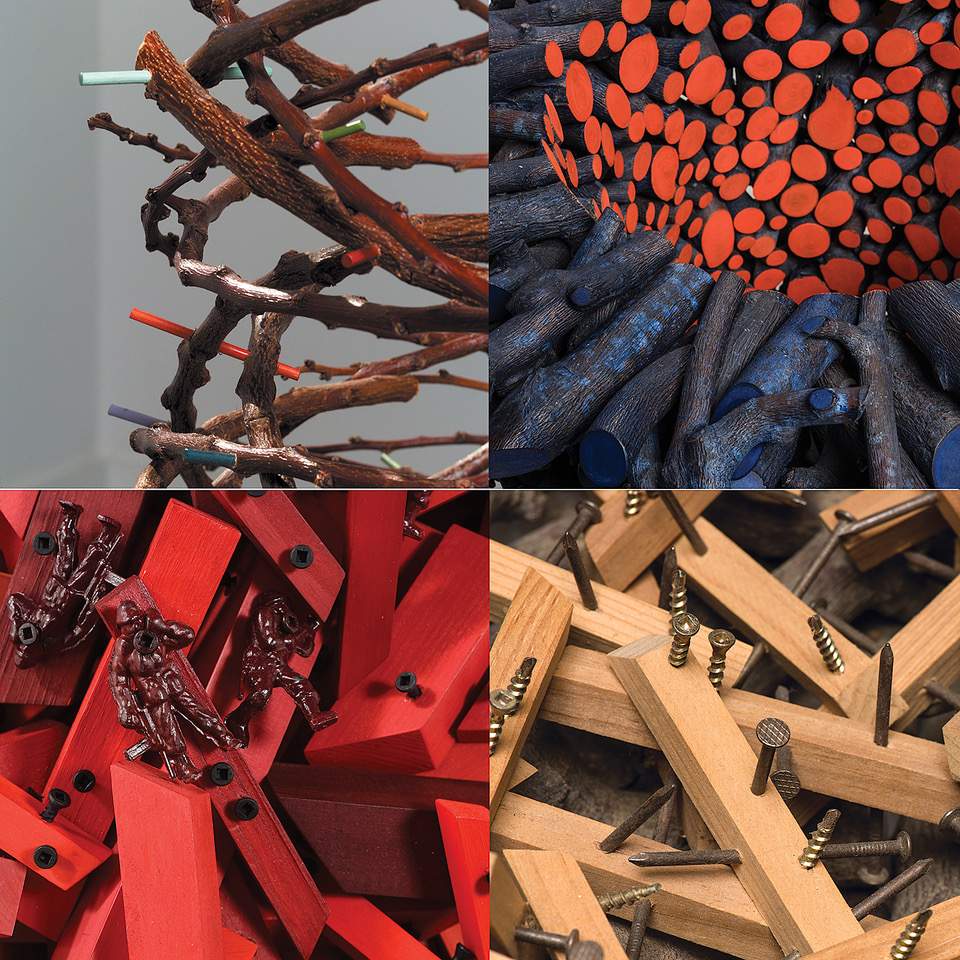

In our recent exhibition, Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber Art for Three Decades, we featured a gallery wall with art by nine international artists from five countries.

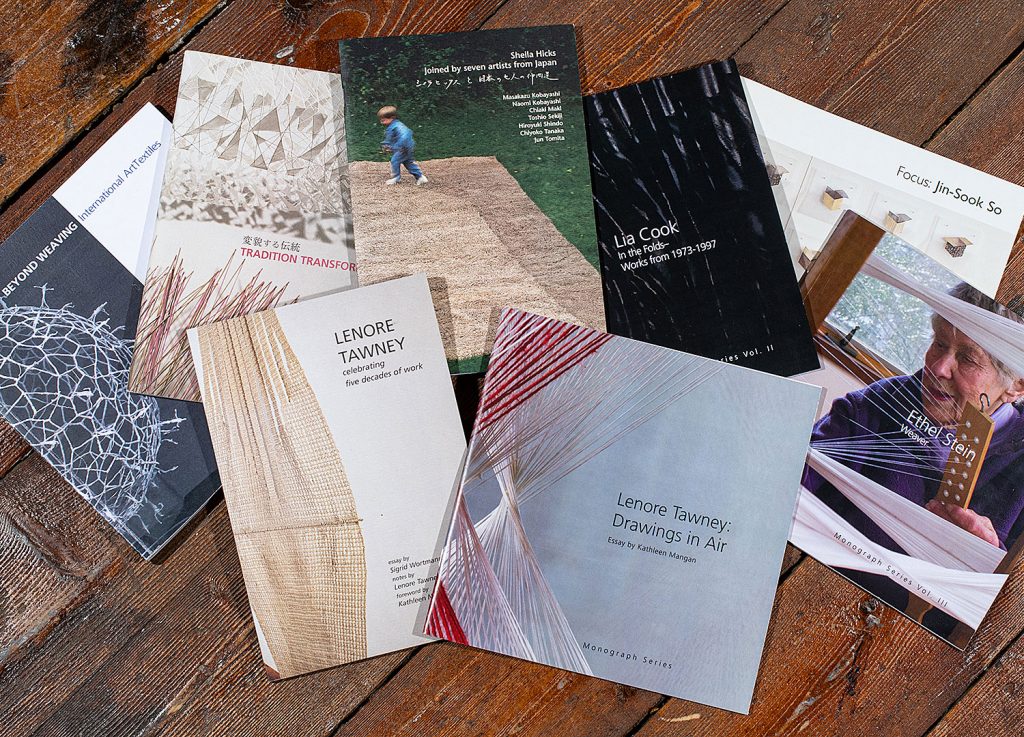

Salon walls, or gallery walls as they are also called, are a favorite with designers, according to Invaluable, for a reason: they can be curated to fit an assortment of styles and work well in virtually any room. (“15 Gallery Walls to Suit Every Style,” https://www.invaluable.com/blog/gallery-wall-ideas/utm_campaign=weeklyblog&utm_medium=email&utm_source=house&utm_content=blog092420 ) Salon walls “first became popular in France in the late 17th century,” according to the Invaluable article. “Salons across the country began displaying fine art from floor to ceiling, often because of the limited space, that encapsulated the artistic trends of the time. One of the first and most famous salon walls was displayed at the Palace of the Louvre in 1670, helping to establish the Louvre as a global destination for art.”

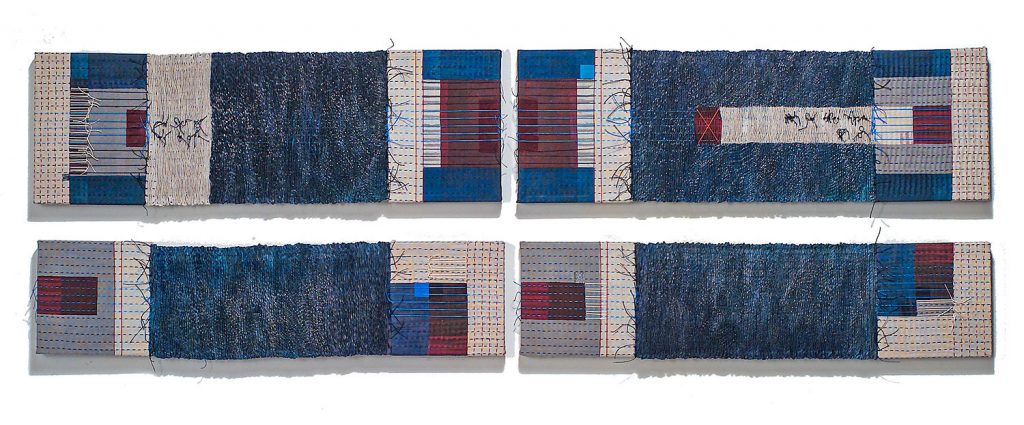

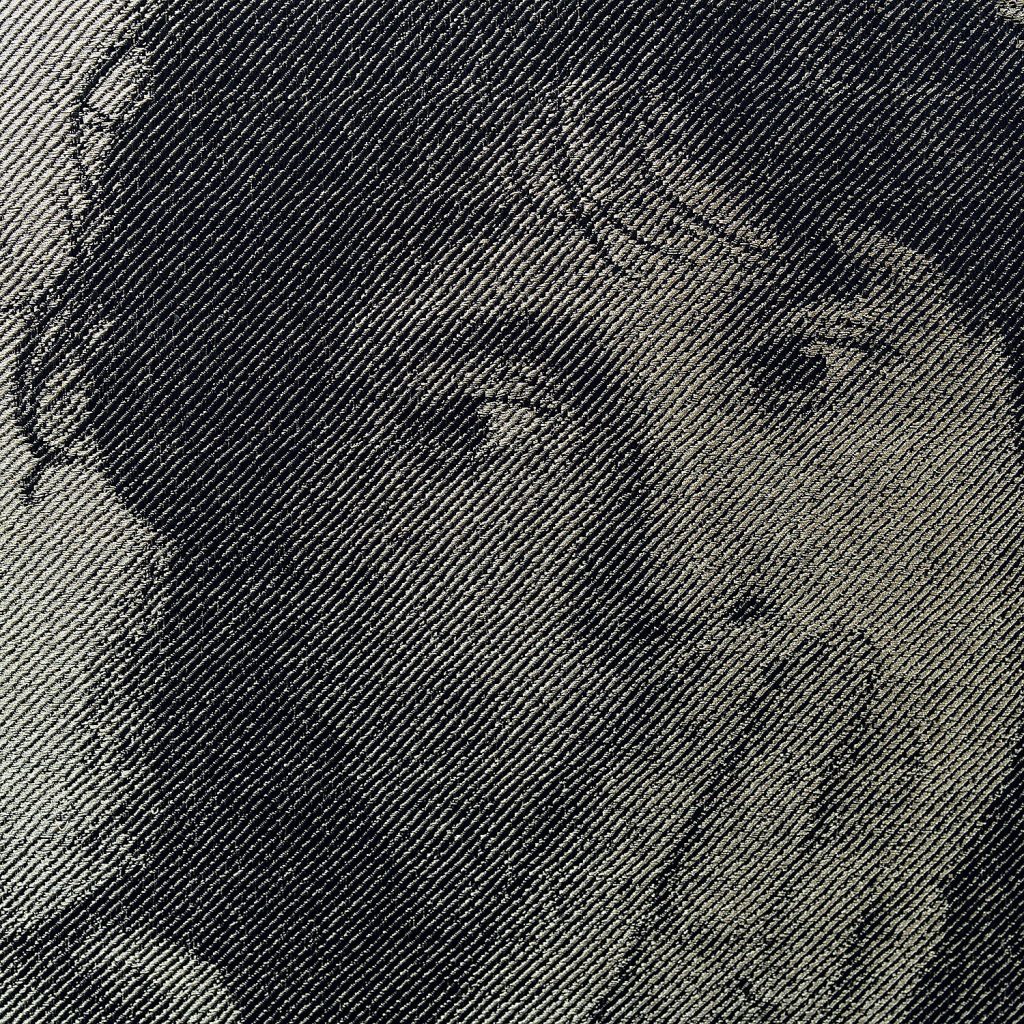

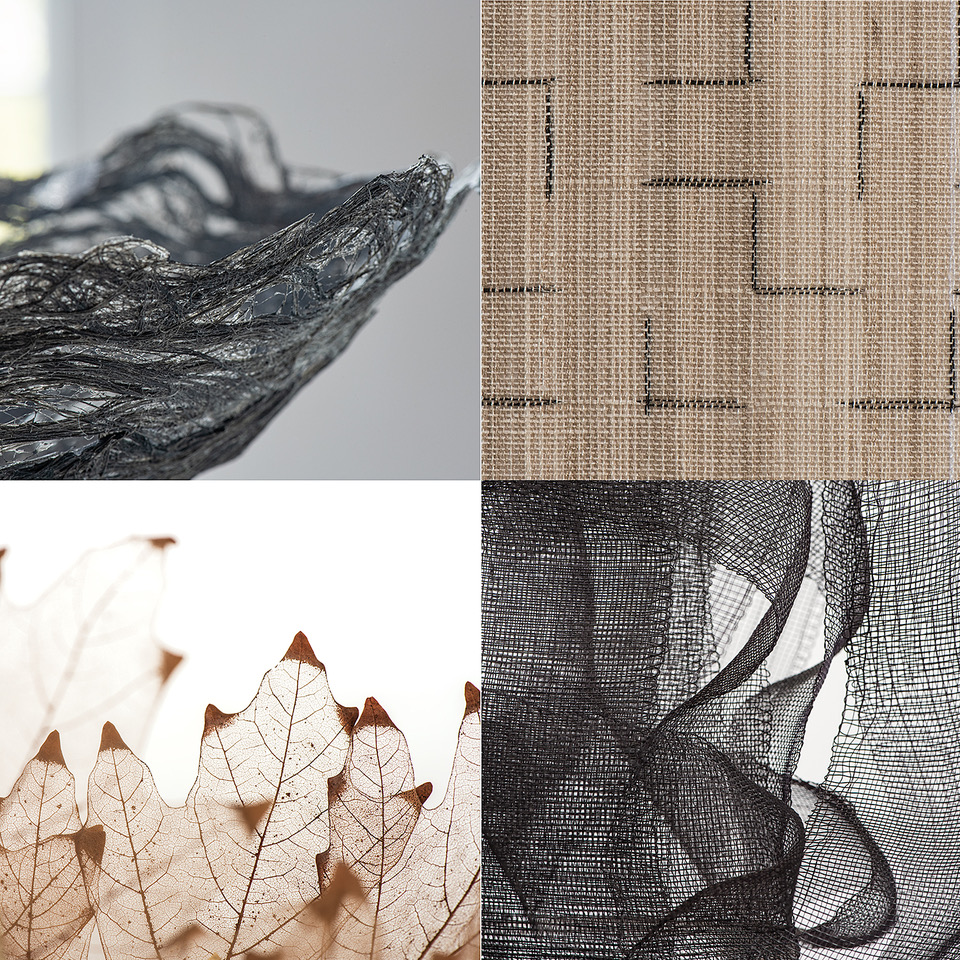

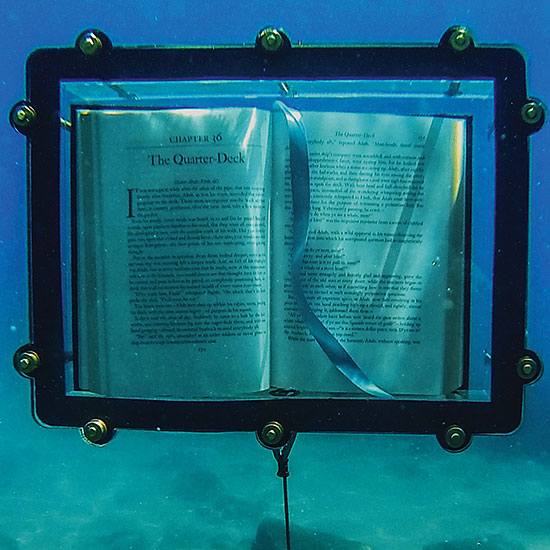

Our Volume 50 salon wall was a fitting testament to the 50 catalogs we have produced and were celebrating in this exhibition. In our 50 catalogs we have featured 172 artists from 28 countries. Our salon wall featured works by nine of those artists from five countries. Wendy Wahl creates work from pages of encyclopedias, leading readers to think about changes over the time to the way acquire information. Mia Olsson of Sweden created a work of brightly colored sisal, inspired by traditional, pleated folk costumes. We included Jo Barker’s tapestry, Cobalt Haze. People often think Barker’s lushly colored tapestries are oil paintings until they are close enough to see the meticulous detail. Lewis Knauss imagined a landscape of prayer flags in creating Prayer Mountain. For Deborah Valoma, simplicity is deceptive. The truth, she says, “scratched down in pencil, lies below the cross-hatched embellishments.”

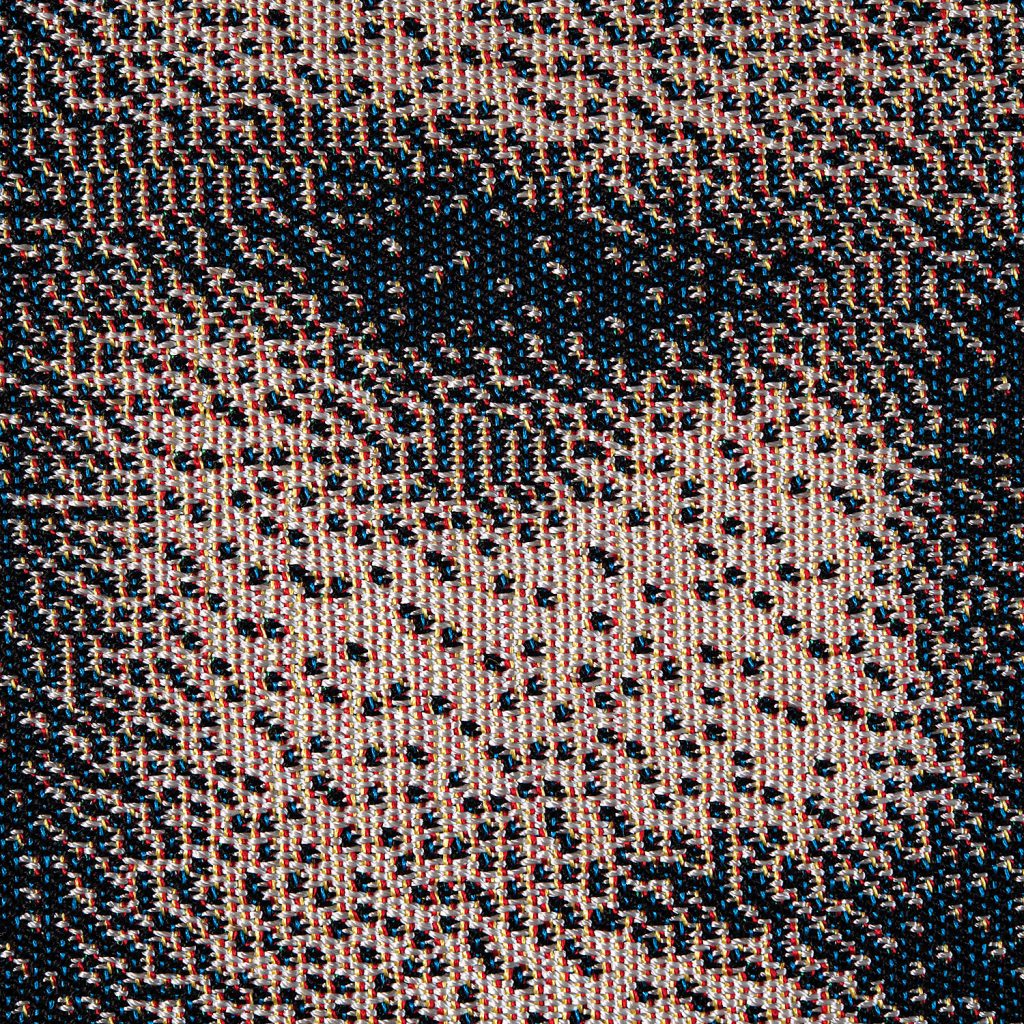

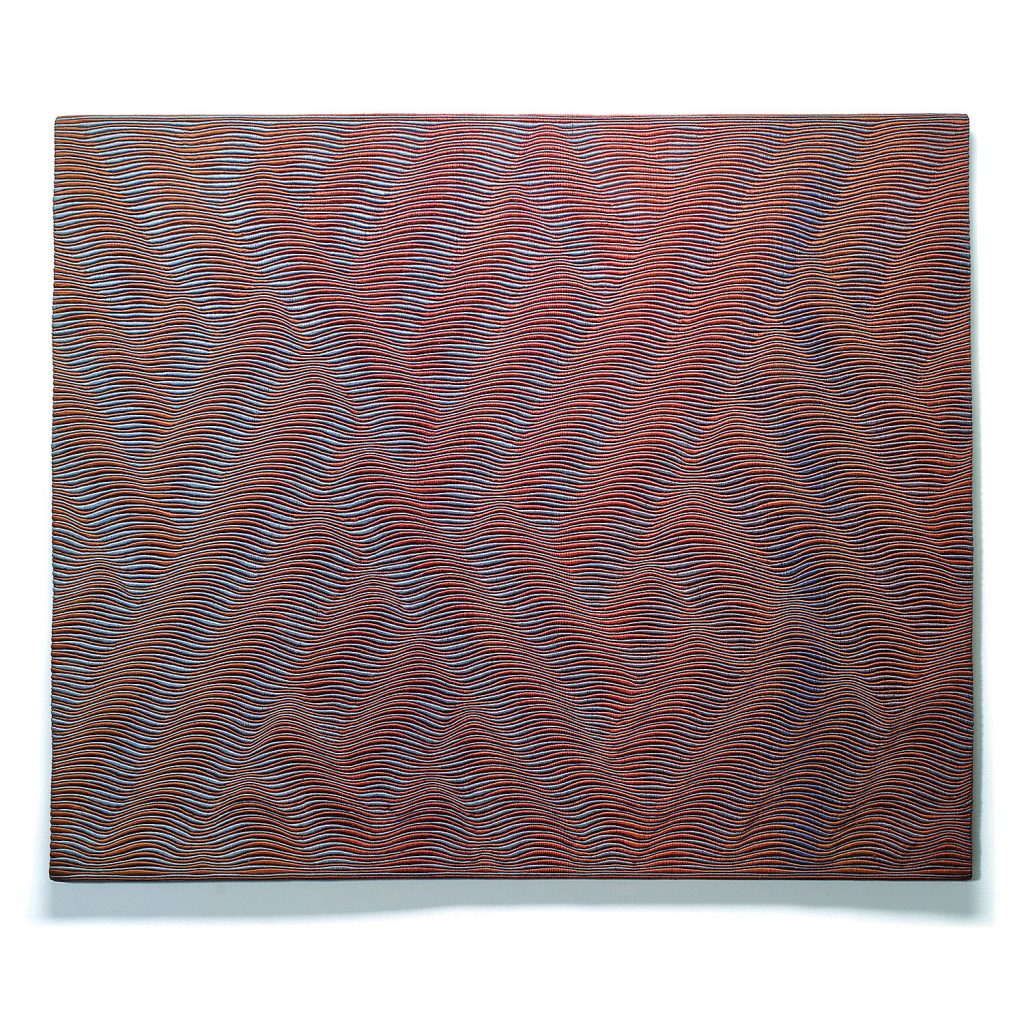

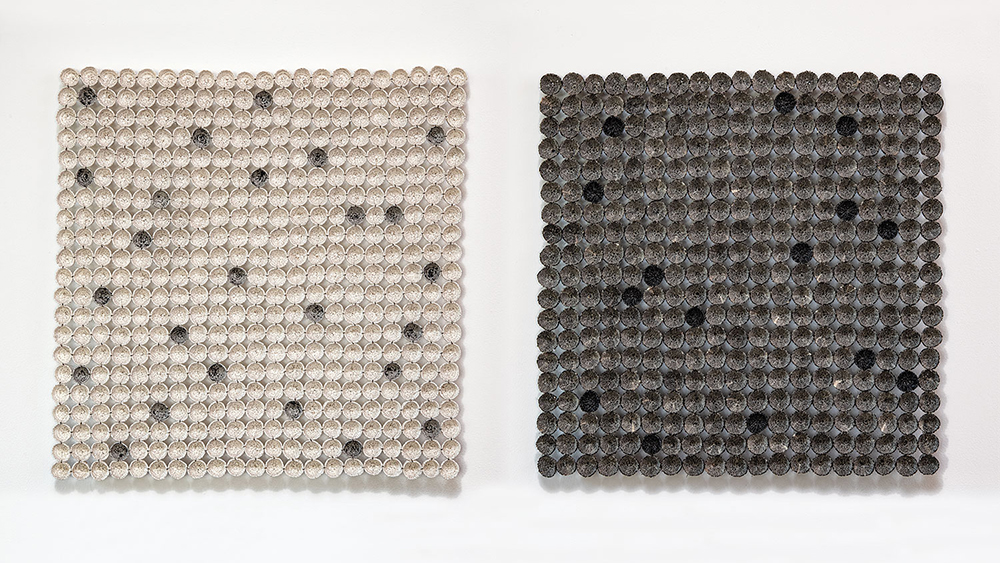

Jennifer Falck Linssen found inspiration in Asian ink paintings for her wall work, Mountain. The peaks in the paintings are a play of opposites: serene and forceful, solid and ethereal, strong and vulnerable. Mountain explores this duality and also the layered, often subtle, emotions of the human heart and its own dichotomy. Marian Bijlenga‘s graphic, playful work displays a fascination with patterning. This work was inspired by the geometric patterning of Korean bojagi, which is comparable to modernist paintings by such artists as Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee. In bojagi,small, colorful leftover scraps of fabrics are arranged and sewn together to construct larger artful cloths. The triple-stitched seams are iconic. This work, says the artist, specifically references the grid of these seams and the special Korean use of color. For Polly Barton, the technique of ikat serves as her paintbrush for producing contemporary works. From Norway, Åse Ljones uses a blizzard of stitches to create her works. “No stitch is ever a mistake,” she says. “A mistake is often what creates a dynamic in the work.”

A salon wall is a great way to collect for people who are interested in different artists and different mediums. At browngrotta we’ve always suggested that clients had more wall space on which to display art — it just hadn’t been uncovered yet. We’ve created another salon wall in our non-gallery space. On it, we’ve combined oil paintings, fiber works, ceramics and photography. The wall can accommodate our continuing desire to collect — above, below and on the side.

“A gallery wall is absolutely ideal for a small apartment, as it can give a room real interest, depth and a properly decorated feel without taking up any floor space — and thereby minimizing clutter,” Luci Douglas-Pennant, told The New York Times in 2017. Douglas-Pennant founded Etalage, with Victoria Leslie, an English company specializing in antique prints, vintage oil paintings and decorative pictures for gallery walls. “If you don’t have one large wall, gallery walls can be hung around windows, around doors, above bed heads, above and around fireplaces or even around cabinets in a kitchen.”

For works of varying sizes and shapes to get you started on your own version of a salon wall, visit browngrotta.com, where we have images of dozens of available artworks to pique your interest.