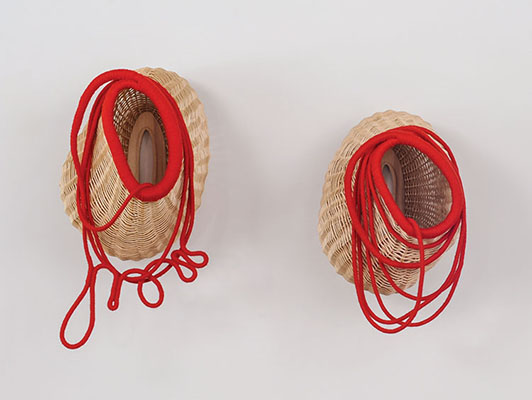

When Green is Gold: Cube connection 14, Noriko Takamiya, paper, 8.5” x 8.5” x 4.5”, 2018. Photo by Tom Grotta

The summer months are coming to an end and the leaves are beginning to fall around us here at browngrotta arts. From Noriko Takamiya ’s When Green is Gold: Cube connection 14 to Nancy Koenigsberg’s Solitary Path, the pieces we shared throughout the summer months presented a deeper look at the diversity of fiber art.

We kicked off September with Noriko Takamiya’s When Green is Gold: Cube connection 14. Takamiya puts a modern twist on traditional Japanese basketmaking methods through her experimentation with weaving techniques. When working on a basket, Takamiya winds hundreds of layers of thin strips of paper around and in between one another until she reaches her desired form. The end result, a three-dimensional puzzle-like basket.

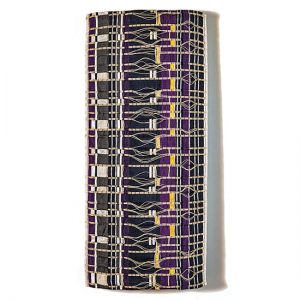

Second in September’s queue was Heidrun Schimmel’s Stitch by Stitch. Schimmel, who has been working with textiles since 1958, hand stitches all her work. Through this process she is able to explore the connection between thread and human: “Mythologically, thread is connected to human existence,” says Schimmel. “Its length and quality are metaphors for the duration and character of our lives.” Schimmel’s creative process is quite simple, she begins her pieces by stitching white cotton thread onto transparent black silk. As she continues to stitch, the tensions between the varying layers of thread create deformations, so “the work itself finds its final form through the combination of control and chance.”

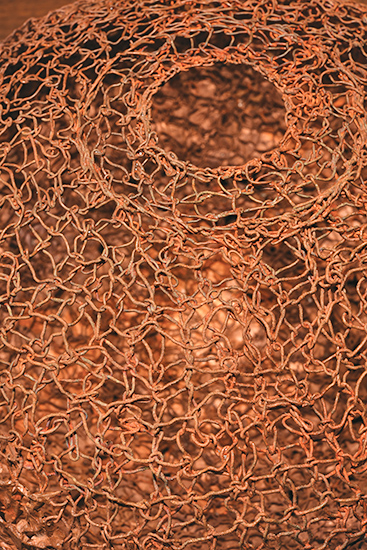

Primary Windows at 22 with Blue Spill on the Sill, Sylvia Seventy, molded recycled paper, wax, button drawings, buttons, beads, feathers, cotton thread, staples, 4.5” x 13.5” x 13.5,”. Photo by Tom Grotta

Next up we featured Californi-based artist Sylvia Seventy’s Primary Windows at 22 with Blue Spill on the Sill. In making her bowls, Seventy carefully molds fibrous recycled paper pulp into her desired form. Through her work, Seventy transforms ordinary materials gathered from her surroundings into extraordinary “mysterious allusions of antiquity.” The walls of Seventy’s vessels contain a record number of processes, that not only mark change, but tracings of times. For Seventy, “Each work documents a layer of my life. Like a patch in a quilt, a photograph in an album, an object in a box of treasures.”

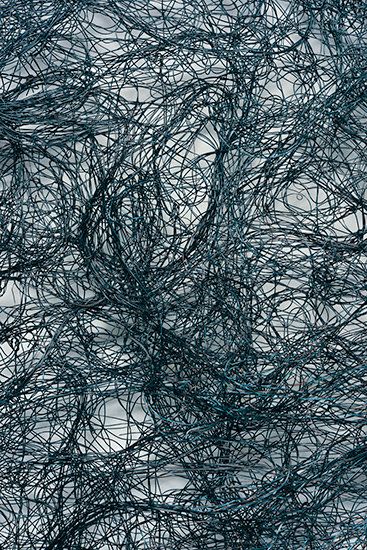

Last, but certainly not least, we shared Nancy Koenigsberg’s Solitary Path. Koenigsberg, who has lived the majority of her life in an urban environment, finds inspiration in the grid-like pattern of New York City’s streets. Made using lace-like layers of coated copper wire, Koenigsberg’s Solitary Path explores the relationship between shadows and space. The contrast between light and shadow transforms her works into a paradoxical study of “delicacy and fragility juxtaposed with the strength of steel and copper employed in their making.”