Artist collaborations account for some of the greatest pieces ever made. For example, the 1874 collaborative exhibition between Monet, Renoir, Morisot, Cézanne in which the called themselves the “Société Anonyme des Artes” helped establish the artists in the art world. In fact, it was a snide remark by art critic Louise Leroy of the show, which he called ‘The Exhibition of Impressionists” that established the impressionist style and movement (Financial Times).

“History has proved time and again that two creative minds can sometimes be better than one,” explains Nadja Bozovic of Agora Gallery. “Even today, artists are increasing collaborating with each other and with creative professions from other fields.” Laura Ellen Bacon and Chris Drury have both collaborated with or inspired creators in different fields, Bacon with composer Helen Grime and Drury with poet Kay Syrad. Historically, many renowned artists have collaborated with their significant others. Artists and couple Debra Sachs and Marilyn Keating were the focus of a collaborative exhibition at the Stockton University Art Gallery in 2016. Collaborations between couples, which require much trust and respect, fuse the differing talents, ideas and creative energies of the individuals. In the end, artists don’t see collaborations as a way to create masterpieces, instead, artists see it as a way to force themselves into uncomfortable territory and break old habits while also breaking new ground. Several of browngrotta arts’artists have been part of these fruitful arrangements, including:

Dail Behennah and Jessica Turrell

Dail Behennah and Jessica Turrell started a joint adventure with their collaborative blog, In.dialogue. Through the years Behennah and Turrell have had numerous conversations about their work. They originally thought that they would create a body of work on a common them, but the more they explored the idea the more they realized it was the conversation around their work they valued the most. “Trust is an important aspect of a project,” Turrell explains “we need to be able to challenge and support each other in the sometimes difficult process of thinking and talking about our work, and of pushing ourselves to do something new.”

Laura Ellen Bacon & Helen Grime

Composer Helen Grime’s piece Woven Space was inspired by the work of Laura Ellen Bacon. Grime was inspired by the way in which Bacon’s sculptures embrace, surround and engulf architecture and natural landscape. Grime’s Woven Space comes from Bacon’s 2009 willow sculpture in the Chatsworth House gardens. Grime did not set out to create a literal musical representation of Bacon’s work sculptural work, instead, she worked to parallel the intertwining limbs of Bacon’s sculptural work with her score.

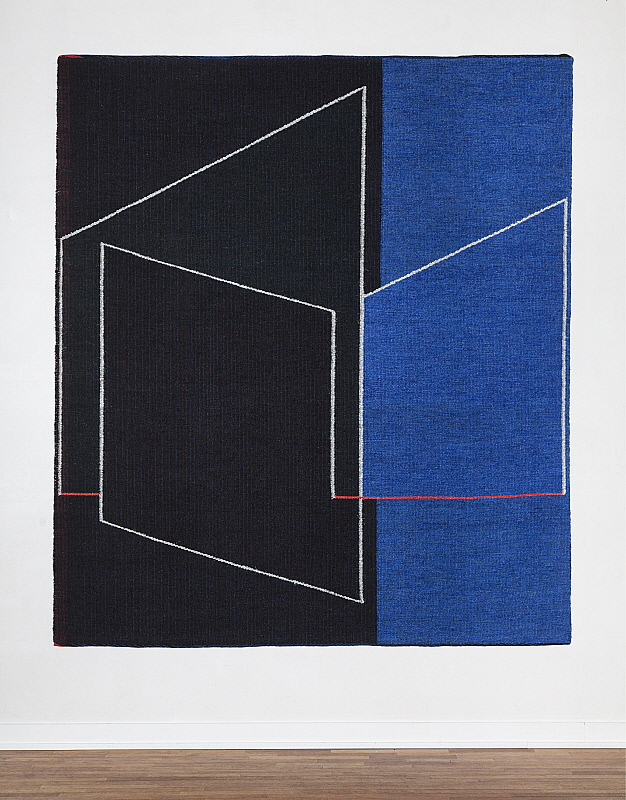

Debra Sachs and Marilyn Keating:

Debra Sachs and her partner Marilyn Keating held a collaborative exhibition at the Stockton University Art Gallery in 2016. The exhibition, titled Going Solo and Tandem, featured individual and joint work the couple produced over the course of 30 years. Sachs and Keating, who met in the early 1970s during their time as students at the Moore College of Art in Philadelphia, are both influenced by their surroundings. Keating, who primarily works with wood, creates depictions of kites, birds, bugs and dogs. Sachs, who mainly works in the form of abstract paintings and three-dimensional pieces, takes a more design-oriented approach to her work. “It’s more about colors and shapes of landscapes,” explains Sachs. “For Marilyn, it’s more about fish and whatever kinds of things you can find. More Narrative stuff. She can make a bird on a band saw. Those are skills I don’t even have.” Though their influences and methods are quite different, the two are able to meld their style when working together. Typically, Keating builds the structures and Sachs designs and paints the structures’ surface.

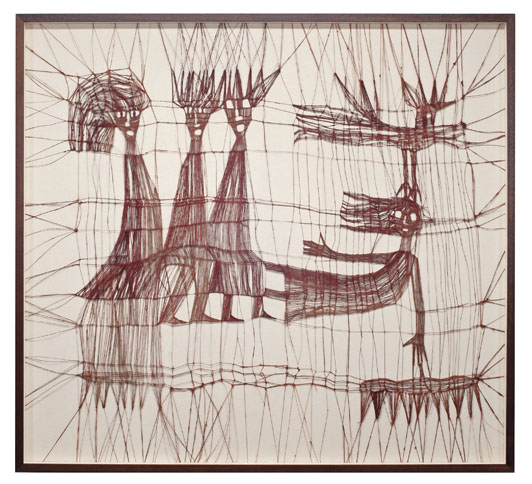

Chris Drury & Kay Syrad

In May, Chris Drury collaborated with Kay Syrad to host a five-day art.earth intensive. Throughout the intensive, titled “Context and Form: Art and Writing,” Drury shared how he works with form, including whirlpool, vortex, fractal and wave patterns. In order to work with such patterns, Drury explores and investigates how the earth unfolds these specific aesthetic forms. Syrad, a novelist and poet, had collaborated with Drury on a number of art-text projects. Participants immersed themselves in the landscape by walking, collecting and working on pieces during short lectures, shared conversation and studio time.

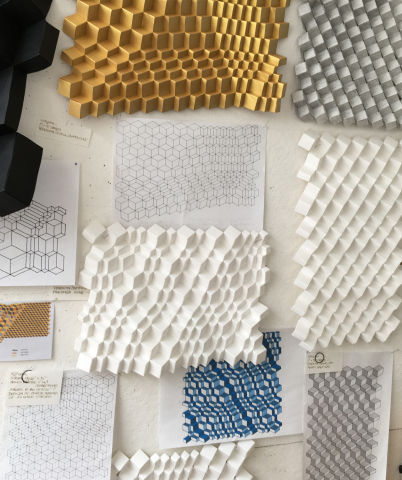

Lawrence LaBianca and Donald Fortescue

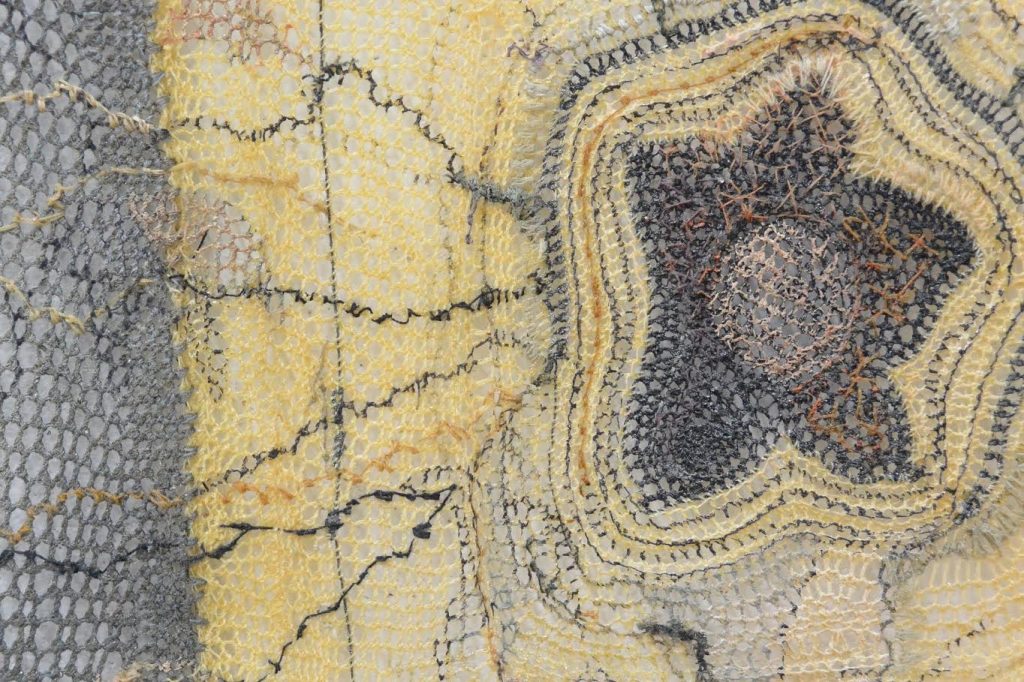

In 2011, Lawrence LaBianca collaborated with Donald Fortescue to create Sounding for the Milwaukee Art Museum’s exhibition The New Materiality: Digital Dialogues at the Boundaries of Contemporary Craft. The artists selected for the exhibition were established American crafts artists who blended traditional craft materials (i.e. fabric, glass, wood, metal and clay) with digital technologies, therefore, blurring the boundaries between the traditionally established categories of craft, art and design. Sounding, which happened to be one of the largest pieces in the exhibition, explored the relationship between technology and nature. In making Sounding, Fortescue and LaBiance were inspired by Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. The artists’ fascination with Moby Dick came in part from “its detailed evocation of the bygone crafts of sailing and whaling and the struggles of men at sea.” The two lowered a cabriole-legged table into the ocean near Pillar Point in Half Moon Bay with a hydrophone and left in in the ocean for two months to record the ambient sound. “Sounding provides a direct link to the living oceans surrounding the Bay Area through sight, sound, smell, and touch. In both form and concept it also links to the historical, literary, and metaphorical oceans of Moby-Dick,” explains LaBianca