Things certainly don’t slow down in the summer over here at browngrotta arts, and July was a testament to that. This month, we’ve introduced you all to works by Lewis Knauss, Shoko Fukuda and Laura Foster Nicholson in our New This Week series. Read on to see what impressive work these artists have been busy creating.

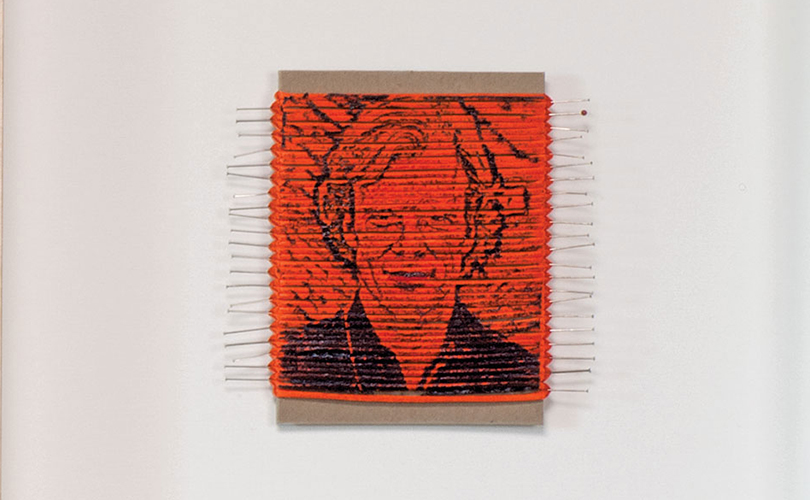

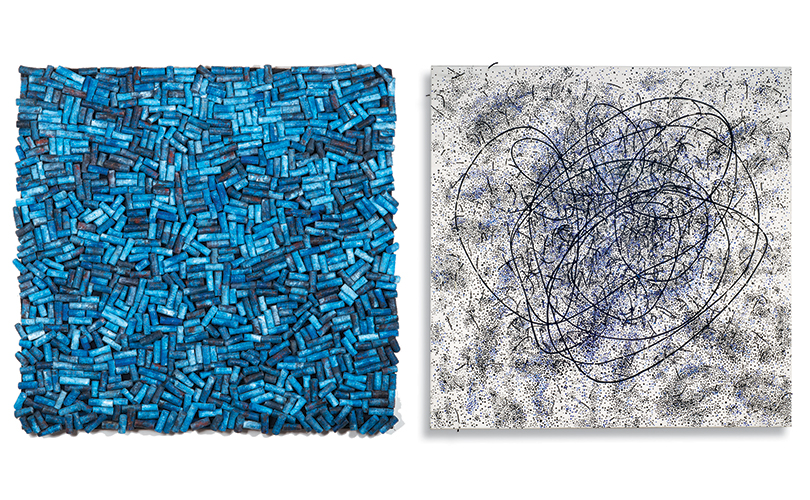

This colorful piece was created by American artist Lewis Knauss. This particular work was inspired by the environment; more specifically, fires and climate change that has occurred as an impact of over consumption of fossil fuels.

Knauss uses his work as a tool to explore his memories of place and his surroundings in a meaningful way.

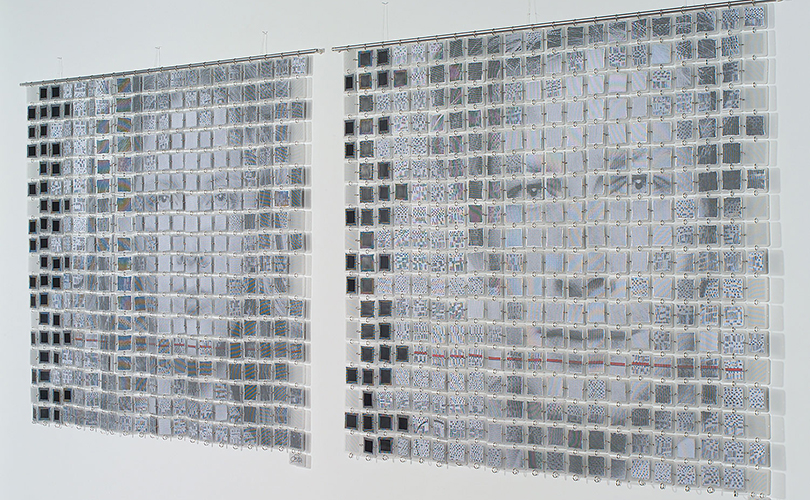

This complex and ethereal artwork comes from Shoko Fukuda. Fukuda is a basketmaker and Japanese artist that’s been making monumental strides in the art world for over a decade. Often, her work features materials like sisal, ramie and raffia.

She has said she’s interested in “distortion” as a characteristic of basket weaving:

“As I coil the thread around the core and shape it while holding the layers together, I look for the cause of distortion in the nature of the material, the direction of work and the angle of layers to effectively incorporate these elements into my work,” said Fukuda. “The elasticity and shape of the core significantly affect the weaving process, as the thread constantly holds back the force of the core trying to bounce back outward.”

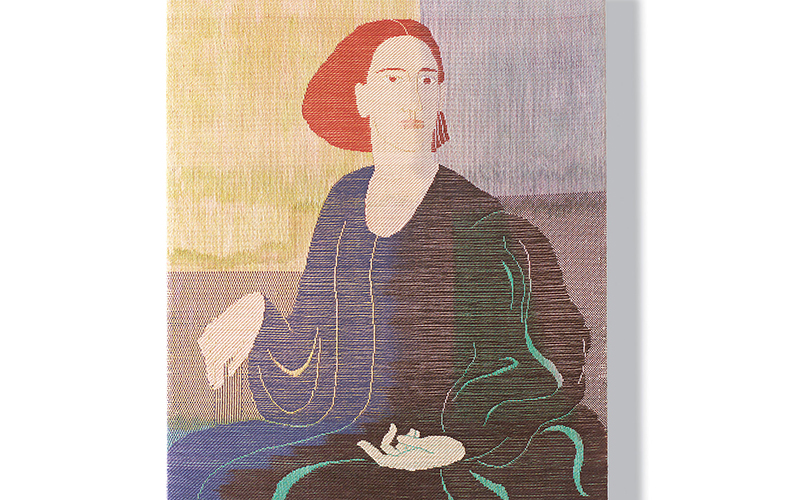

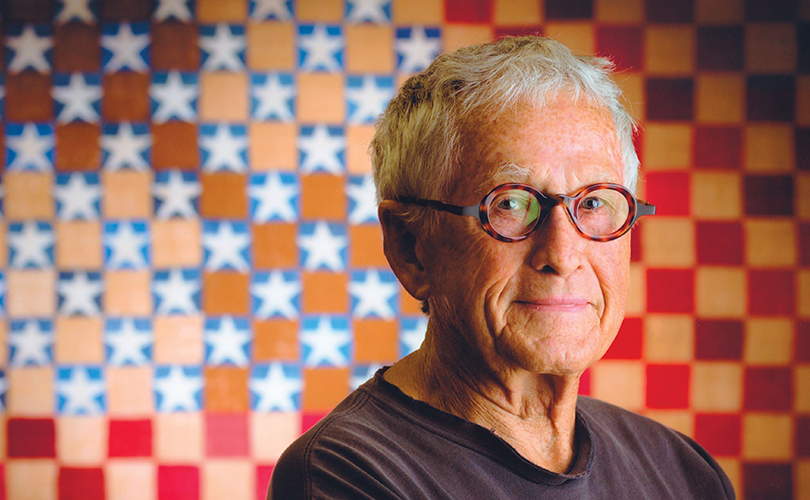

Last, but not least, we introduce you to the unique textile artwork of Laura Foster Nicholson. This American artist is known for her powerful hand woven tapestries that feature whimsical, engaging imagery. Much like the work of Lewis Knauss, Nicholson’s work is often created with the state of the world in mind – including theme’s of how climate change and over consumption is impacting our world today.

With fall quickly approaching, we want to give you all plenty of warning that we have some very exciting exhibitions in the works for you all. Keep your eyes pealed and follow along to see what impressive artwork we bring into our fold in the months to come!