Indigo dyeing is a universal practice. Textiles are produced with indigo throughout America, China, India, Africa, Central Asia, Japan, Laos, and Vietnam. “The process unfolds in the same manner the world over, involving exactly the same steps: cultivation or wild harvesting of the plant, extraction of the pigment, preparation of the dye bath, and dying of the cloth or yarn,” says Catherine Legrand, author of the gorgeous and expansive book, Indigo: the Color that Changed the World (Thames & Hudson, London, 2013). “The weaver and/or tailor or embroiderer then transforms the dyed cloth into garments of sublime beauty. From one end of the globe to the other I have seen people who work with indigo as if spellbound by its potential for for magical transformation.”

Many of the artists at browngrotta arts work with indigo. Search for indigo on browngrotta.com and you’ll find 81 works from Asia, the US, Europe, the UK and Venezuela. The artists include Ethel Stein (US), Hiroyuki Shindo (JP), Yeonsoon Chang (KO), Chiyoko Tanaka (JP), Glen Kaufman (US), Susie Gillespie (UK), Sue Lawty (UK), Heidrun Schimmel (DE), Kiyomi Iwata (JP/US), and Chiaki and Kaori Maki (JP). Among those proficient in ikat are Jim Bassler (US), Eduardo Portillo and Mariá Dávila (VE) and Polly Barton (UK) whose works we loaned to Albuquerque Museum’s 2022 exhibition Indelible Blue: Indigo Around the World and the Denver Botanical Garden’s Indigo exhibition in 2023. These four share some of their thoughts on indigo below.

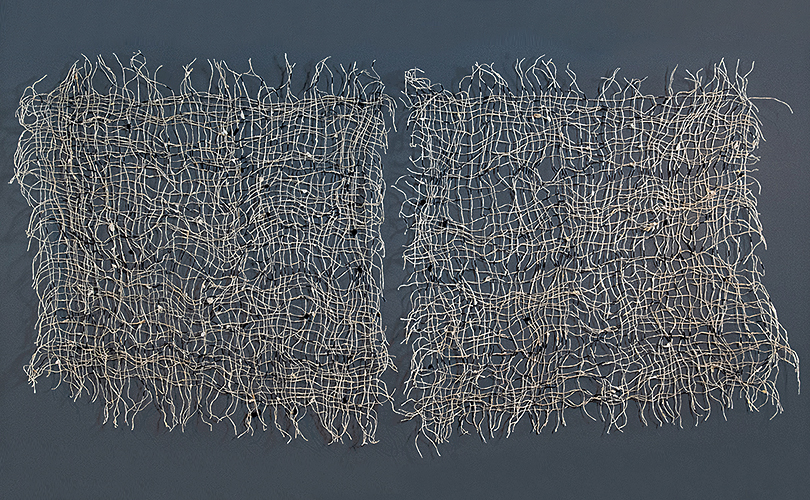

“When we lived on the Pacific coast,” Jim Bassler (US) says, “I maintained an indigo pot most of the time. In the 1990s I became interested in a particular process used in Africa, with indigo, called beetle. It involved pounding the finished linen cloth with a wooden mallet called a beetle, to put a glossy finish on the cloth by flattening the fibers. I wove four wedge-weave tapestries. After weaving them, I would put them on a flat cement surface, run water over the surface and beat them with a wooden mallet. After a few mishaps — holes in the cloth — I learned to temper my force. The weavings became very stiff and flat. The interlocking linen fibers were locked into position. The series, all blue and natural linen, was based on a wedge shape, going from large to small.”

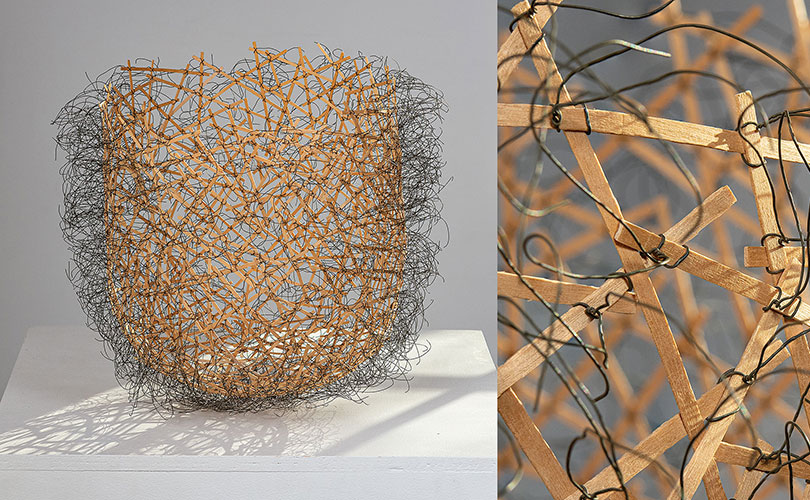

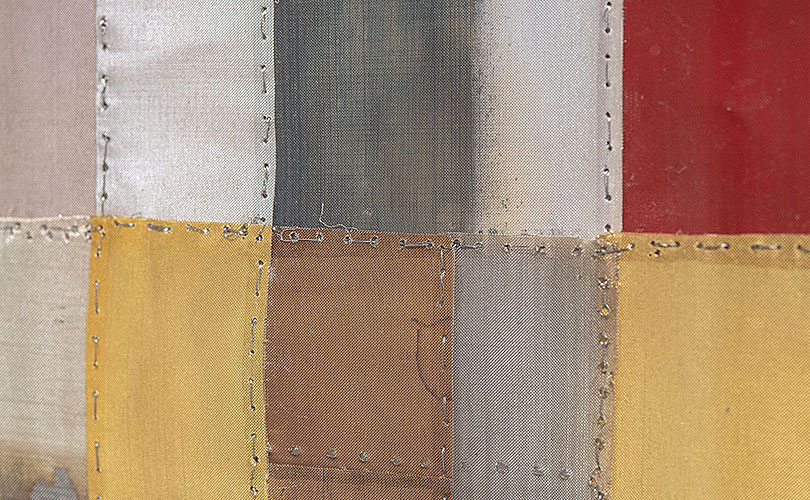

Eduardo Portillo and Mariá Dávila in Venezuela also write about the indigo vat. “To travel in search for Indigo could be a motive for a lifetime itself, every “vat” is different, each vision is unique, a synthesis of history, culture and life,” the couple says, “at last we decided to try to find our own blue and attempted to interlace this color with our searches, exploring the art of indigo dyeing, immersed in their vats again and over again, and bringing it to textiles structures that move us near to everyday blue moments: the night, the moon, the sky, the clouds, dawn, moments of everybody, moments filled with blue.”

Indigo is the ultimate blue. It’s thought to be the color of wisdom and intuition, promoting deeper focus. “Blue is a color of multiple meanings,” say Portillo and Dávila. “It is also the color of hope as every day dawns and the blue accompanies us in the sky, in the sea and in the distant mountains. In 2002 we found the indigo blue and drew lines to see the color of the peoples of Southeast Asia, of the Desert’s blue men, the Andean textiles and blue jeans, the eternal blue.”

Indigo is the ultimate blue, thought to be the color of wisdom and intuition, promoting deeper focus. “Blue is a color of multiple meanings,” say Portillo and Davilá. “It is also the color of hope as every day dawns and the blue accompanies us in the sky, in the sea and in the distant mountains. In 2002 we found the indigo blue and drew lines to see the color of the peoples of Southeast Asia, of the desert’s blue men, the Andean textiles and blue jeans, the eternal blue.”

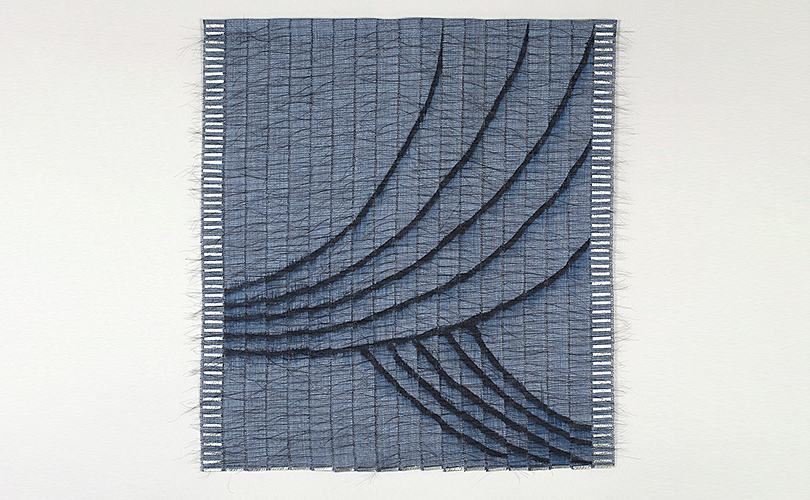

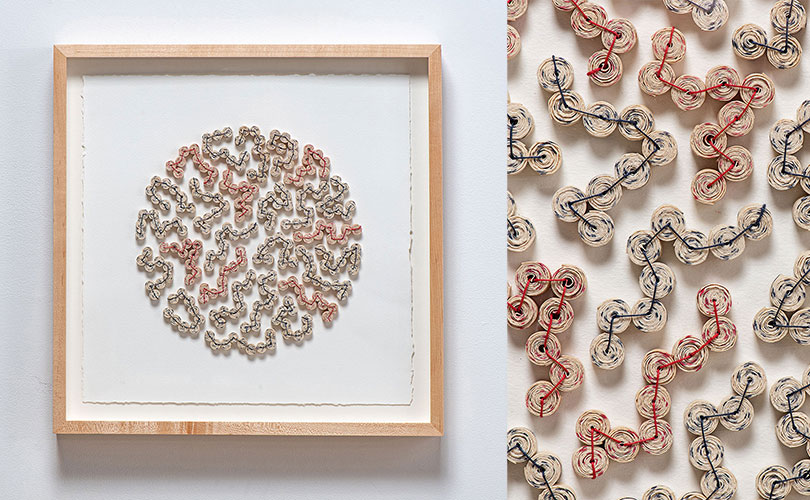

The complex colors of indigo, which Polly Barton (US) often incorporates into her work, were an inspiration for her work Synapse. In making Synapse, Barton was inspired by a drawing of the shadow cast by her swift— the weaver’s tool for unwinding thread from a loose bundle onto a useful, untangled spool. “At the time,” she says, “my father had succumbed to Alzheimer’s.” Barton saw the “swirls of indigo blues, deep and cloudy, tied and locked into threads, as memories slipping away.”

Portillo and Dávila consider it a privilege to get closer to the processes to obtain indigo and to be part of the continuity over the time by using this unique color. “In a certain way,” they say, “we feel the imprint of those who preceded us is also reflected in our work.” To the couple, textiles represent a way of thinking. They are “a means of expression in which some materials have their own voice and contribute in the construction of an idea, they are tangible and identifiable and may contain a history which does not necessarily have to be known to appreciate its attribute.” This is the case with indigo, “one of the oldest known dyes whose complex production methods has been created over the time according to the nuance of each culture fusing the past, present and future in a single color.”