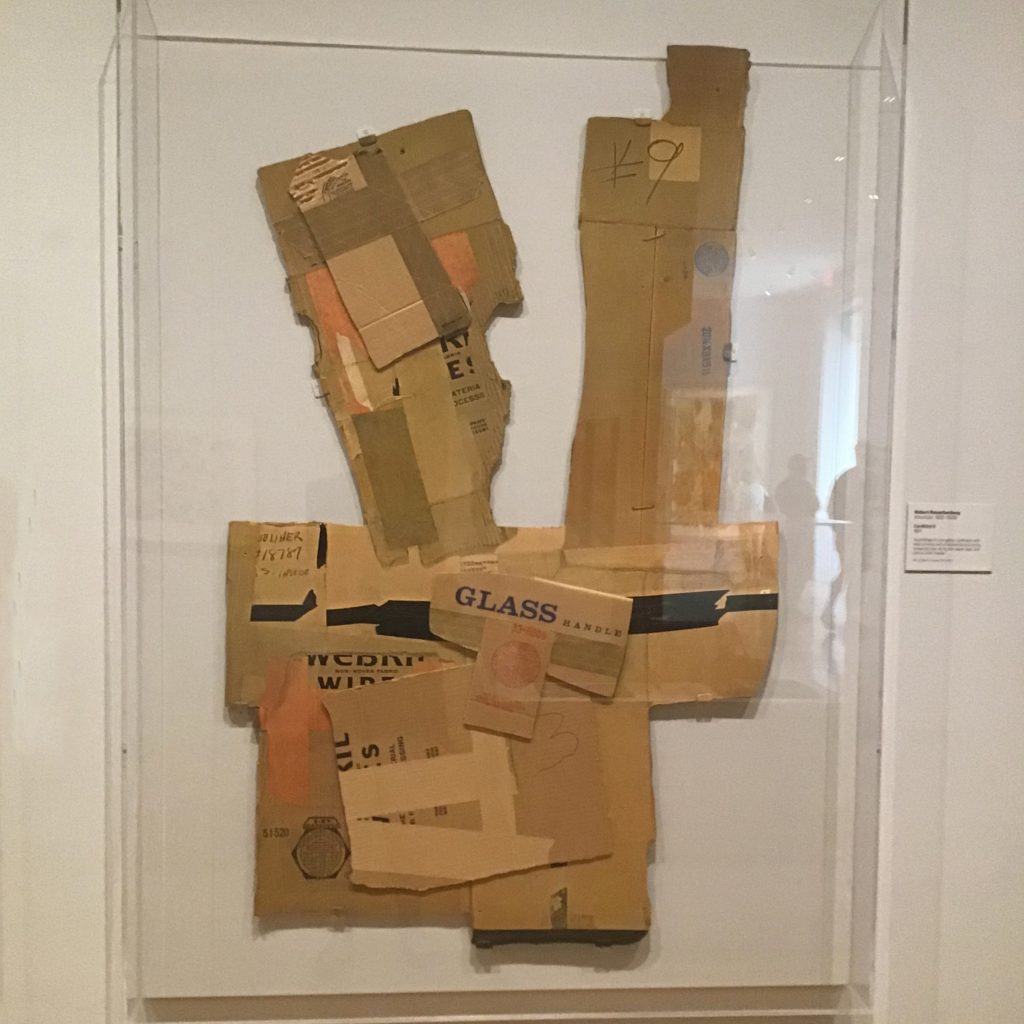

There are no end to art and historical treasures in Philadelphia and Rhonda had a chance to meet up with some good friends and take in a few last week. The Philadelphia Art Museum is a wonder and its annex, the Perelman Building, houses two intriguing exhibits: Souls Grown Deep: Artists of the African American South and The Art of Collage and Assemblage through September 2nd. Souls Grown Deep combines and extraordinary collection of textile art, sculpture, and painting acquired from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

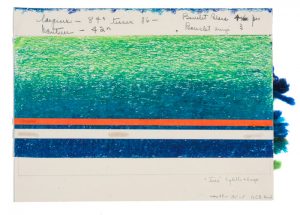

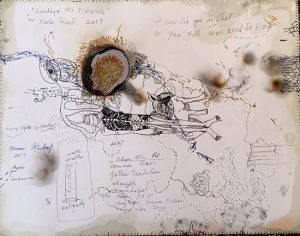

With remarkable inventiveness, generations of quilters from Gee’s Bend, Alabama have created arresting compositions of color and form from worn-out clothes and other repurposed fabrics. Provocative mixed-media paintings and found-object sculptures by Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley and others are displayed amongst the quilts, whose subjects and materials echo with the painful history of the American South and the conditions of life for many who live there. The collage exhibition includes works by Joseph Cornell, a personal favorite, and other less-expected names including Romare Bearden, Bettye Saar and Pablo Picasso.

Lonnie Holley/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio/Art Resource (AR), New York

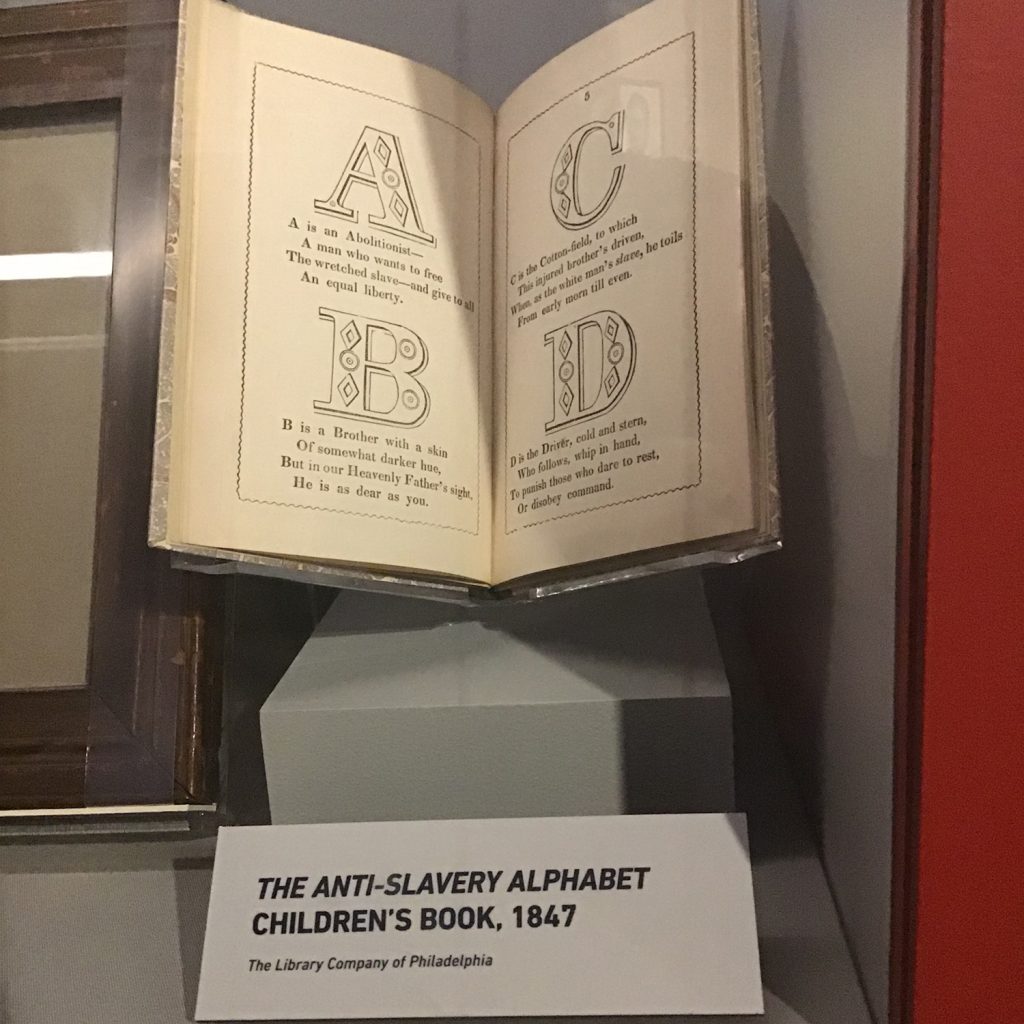

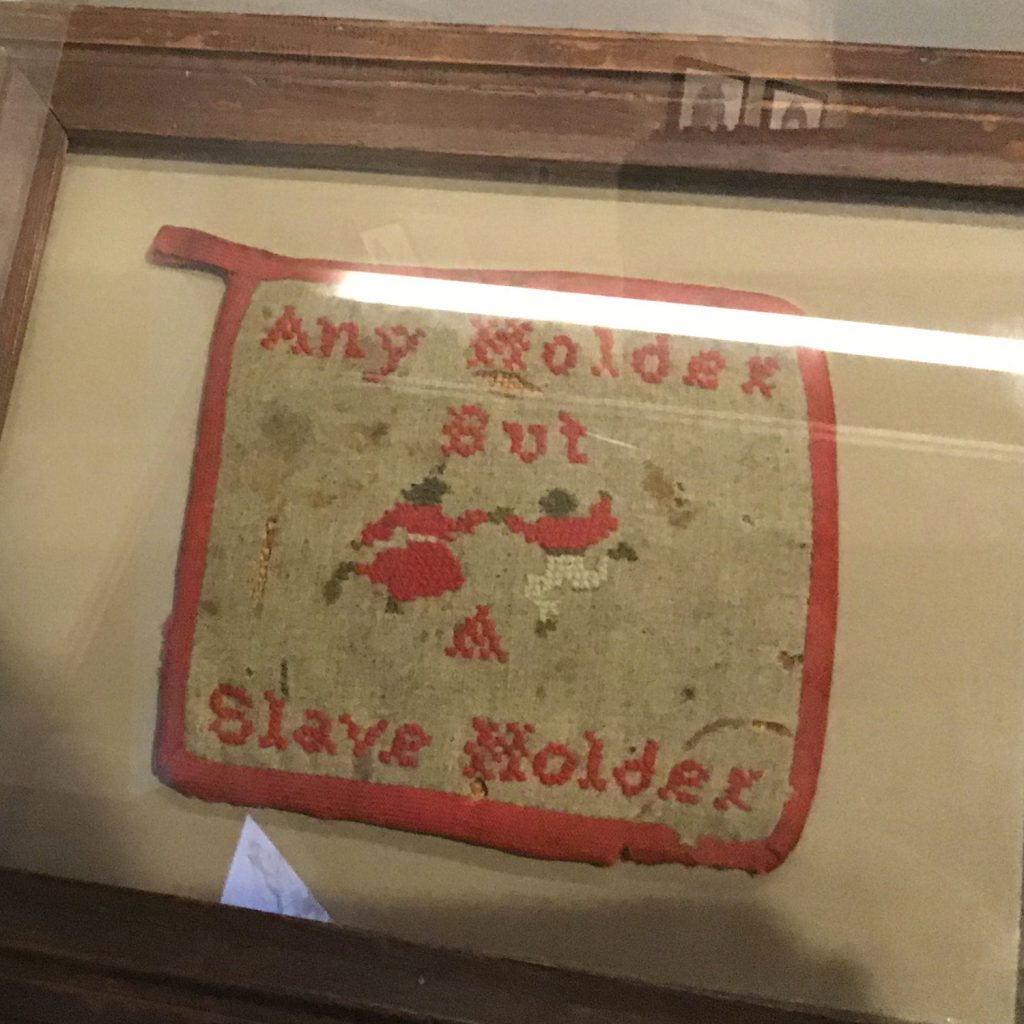

We found artfulness of another kind at the National Constitution Center’s new permanent exhibition, Civil War and Reconstruction: The Battle for Freedom and Equality. Some interesting textiles are on display, including a fragment of the flag that Abraham Lincoln raised at Independence Hall, 1861 (From the Collection of the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia on loan from Gettysburg Foundation) and an embroidered potholder that reads, “Any Holder but a Slaveholder.” We also appreciated the Anti-Slavery Alphabet from 1847.

The exhibition has an ambitious premise, to illustrate how the nation transformed the Constitution after the war to more fully embrace the Declaration of Independence’s promise of liberty and equality. The 3,000- square-foot exhibit brings to life the stories of Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, Harriet Tubman and other figures central to the conflict over slavery. It features the stories of lesser-known individuals, too, in order to shed light on the American experience under slavery, the battle for freedom during the Civil War and the fight for equality during Reconstruction, which many call the nation’s “Second Founding.” Highlighted are the three constitutional amendments added between 1865 and 1870, which ended slavery, required states to respect individual rights, promised equal protection to all people, and expanded the right to vote to African-American men. The exhibition covers, as the Wall Street Journal terms it: “the racially egalitarian society that was briefly wrestled into being after the abolition of slavery, before the ravages of Jim Crow and the hard-fought triumphs of the civil-rights movement.”

The artfulness is evident in the matter-of-fact way the signage and artifacts give equal time to the efforts made to reach equality and those determined to subvert each of those amendments — including displays about Ku Klux Klan, complete with original robes, which were not white but maroon and heavily ornamented. Also edifying and persuasive is the neutrally presented, but inescapable, evidence that the goals of these amendments are yet to be achieved. An example, noted by one reviewer, is the 13th Amendment. “The interactive displays…show the debates, the drafts, and the redrafting of those amendments and help to explain how the final draft [of the 13th] actually allowed forced labor ‘as a punishment for crime’ … It does not take long to make the connection between the 13th Amendment and the shockingly profitable system of prison labor and prison farms which still exists today.” (Margaret Darby, Exhibit Review: Civil War and Reconstruction Phillylifeandculture.com, May 9, 2019).