In our New this Week feature this past month, we shared works from our Spring exhibition, Field Notes: an art survey. First up was Hisako Sekijima’s 32 Selvages with 16 Ends. Always experimenting, this work resulting from Sekijima’s exploration of coarse Mexican dishcloths that were a kind of a four-selvage cloth made from one continuous thread. When she fully understood the unusual movement that made it, economizing repetition of passing a warp, she was “excited to have discovered a new rule hidden in such an ordinary-looking fabric.” She created her own weaving board with 18 rows of lines in two directions. She used a lightly processed fiber in varied sizes, peeled from ramie raised in her garden. She connected lengths each time she needed more, creating a stack of squares this way. “This very primitive weaving method reversed my pre-fixed judgments about weaving, she says, “and made me reconsider the relation of fabrication method and form of material.”

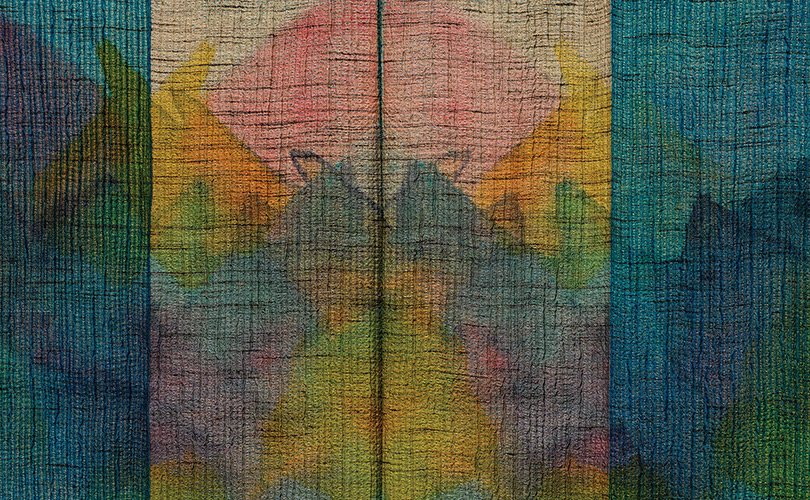

Misako Nakahira is an artist who exhibited with browngrotta arts for the first time in Field Notes. Her exploration of stripes began five years ago, inspired by reading Michel Pastoureau’s The Devil’s Cloth, which explores stripes in Western culture from the Middle Ages to the present. Originally, identifying individuals affected by plagues or those ostracized by society, such as prisoners and prostitutes, Pastoreau concludes that “stripes are patterns that establish order between people and space.” Nakahira uses stripes to explore social phenomena, including the “echo chamber” in which people encounter only opinions that agree with theirs, creating the illusion of intersecting orders among individuals who have never met in person. Towels O incorporates the colors yellow and orange, which, like stripes, signify “caution.” The layers created by the two-stripe patterns may appear to clash or harmonize depending on perspective, yet neither pattern dominates the other. Nakahira believes that using stripes as a motif—a universally understood and versatile form of expression—provides a way to view society from a broader perspective and interpret the times.

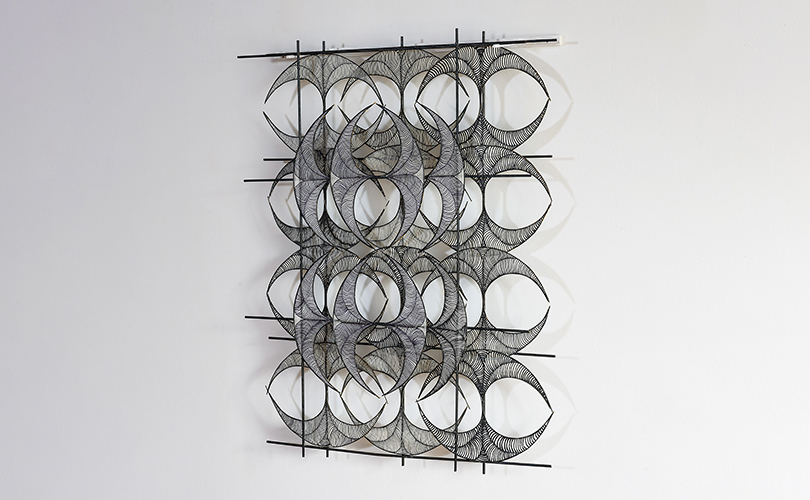

“My work is heavily rooted in ideas of time and space,”says Rachel Max. “For several years I have been exploring notions and forms that symbolize infinity. The Möbius loop and figure 8, both steeped in metaphorical associations, have become my starting point. Each new piece becomes a variation on previous works, an amalgamation of different ideas set to challenge when the infinite becomes finite.” Rift explores the relationship between interior and exterior space. Edges that are almost touching suddenly split apart.The crack that emerges, interrupts the surface and casts doubt on whether this is a never-ending form.

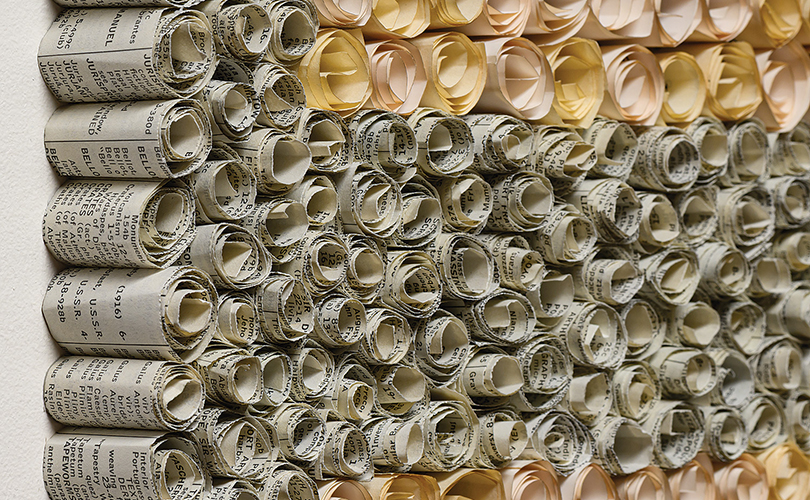

The fourth work for June was Play of Opposites, by Pat Campbell. Campbell’s work is influenced by the Japanese shoji screen, traditionally made of rice paper. “Paper is a natural choice of material for my work. It provides the translucency I am seeking in constructions. It also provides a thin plane of material that is easily shaped and accepts the reed, wood and paper cord that I apply to it,” Campbell says. “Paper is exciting to work with. It is a fragile material that can be easily ripped or torn.” Play of Black and White is constructed of modules that form a configuration hanging on two levels. “I usually work in all white gampi paper,” says. “I experimented here by adding black lines to the rice paper. In future work, I may continue adding color to the modules.”

Hope you enjoy these engaging works!