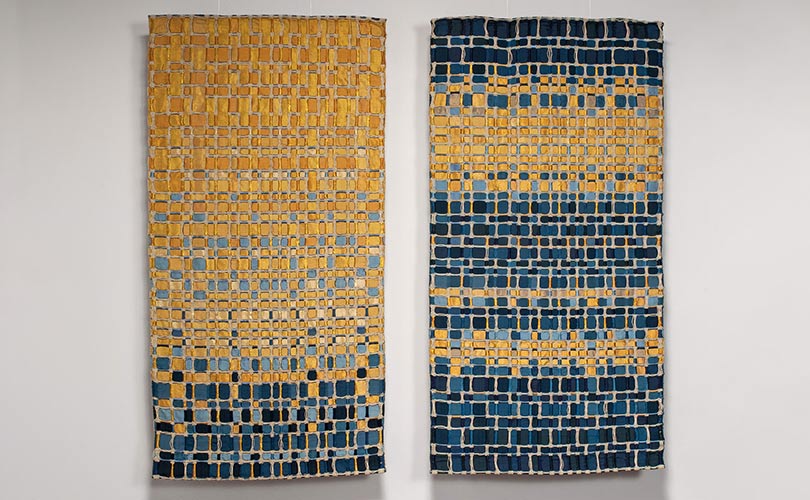

Below, the second installment of Eduardo Portillo’s and Maria Dávila’s textile travels. In this post, they share their inspirations and plans for future work, in which they will continue to combine colors and textures “to conceive moments in which everything is possible, that moment capable of creating imagined worlds and impossible journeys.” At the end of Part I, the artists were creating works that reflected the hours of the day — from sunrise to dusk, night and dawn — and exploring their interest in the intensity of blue depending on the light at various times. Here, in additional remarks adapted from their European Textile Network Conference presentation in March, they speak of more experiments.

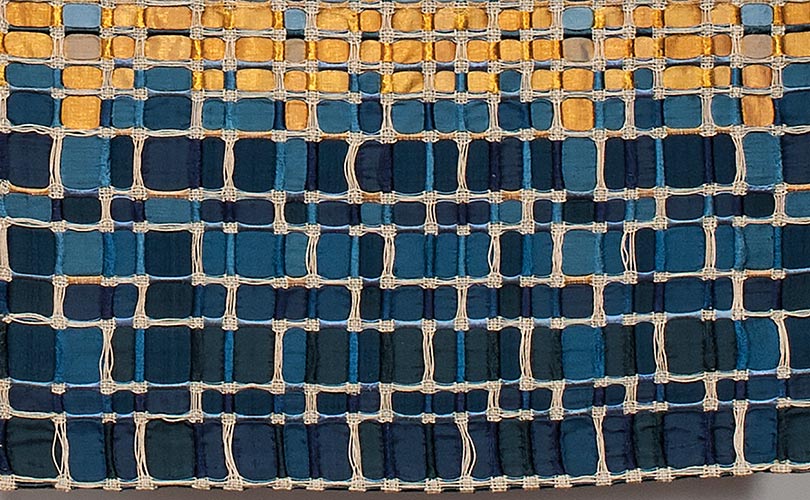

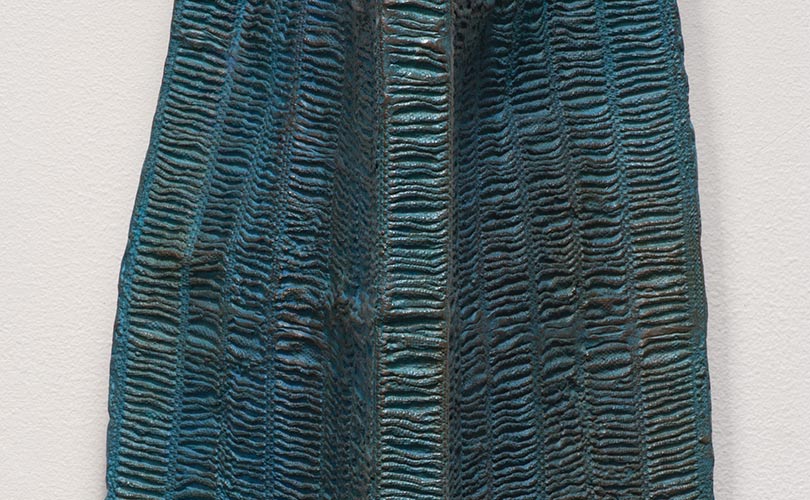

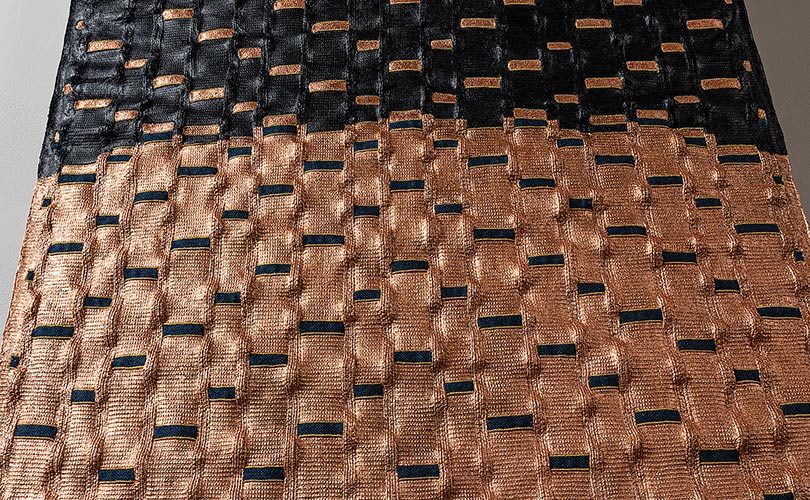

“We began to experiment in a bronze foundry to imagine the passage of time in our textiles — how these would look like many years in the future or as archaeological remains. We experimented with the textiles to recreate shapes, folds and wrinkles. We used textiles to prepare molds for bronze cast. We also explored the patina process in cooper ribbons to mix them with metallic threads and we have woven stainless steel using silk and moriche palm fiber as support.

At a certain moment, due to the growing political conflict in our country, we sought refuge in the mountains and began to travel to places further and further away from our home but still within our region. We visited many remote places with rugged landscapes, places where people continue to live resiliently, understanding the geographic and cultural space in which they live. We tried to see carefully and looked for moments of harmony in mountaineer communities that meet for a common purpose, beyond their differences, especially during the traditional festivals.

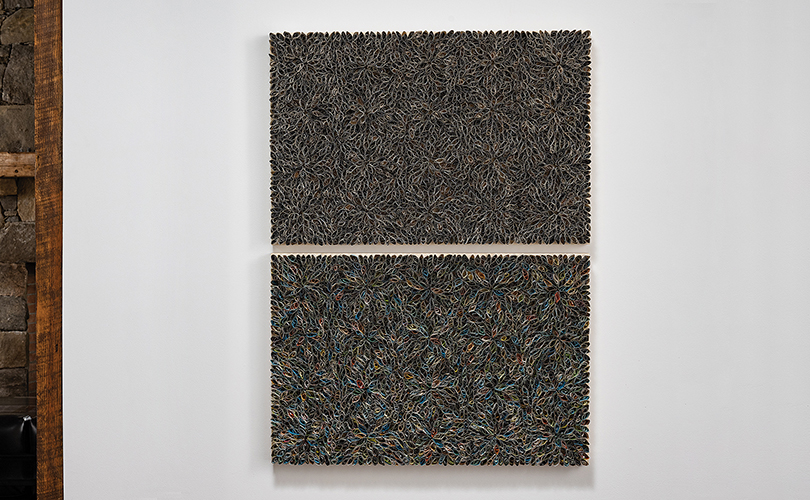

During one of those trips, looking for meanings, we found a very long line in the mountains, like a human drawing on the topography and we wondered what could be this? These are called pit fences. This fantastic and laborious idea of using the void as a border surprised us. The pit fences are made up of hundreds of consecutive deep holes measuring 1m x 2m x 1m, they divide spaces and prevent cattle from falling off cliffs. We were impressed by the capacity of these people to give solutions to a problem in a place where no stones or wood was available.

We got excited about the idea and hope of going through these pits like portals and reaching the universe to find imaginary celestial bodies that exist in the interstellar space like cosmic dust and gases which we have tried to weave and developed Nebulae, White Dwarfs, Stellar Remnants, Moon Codes and Cosmic Oceans, built by spaces of colors and textures to conceive moments in which everything is possible, that moment capable to create imagined worlds and impossible journeys.

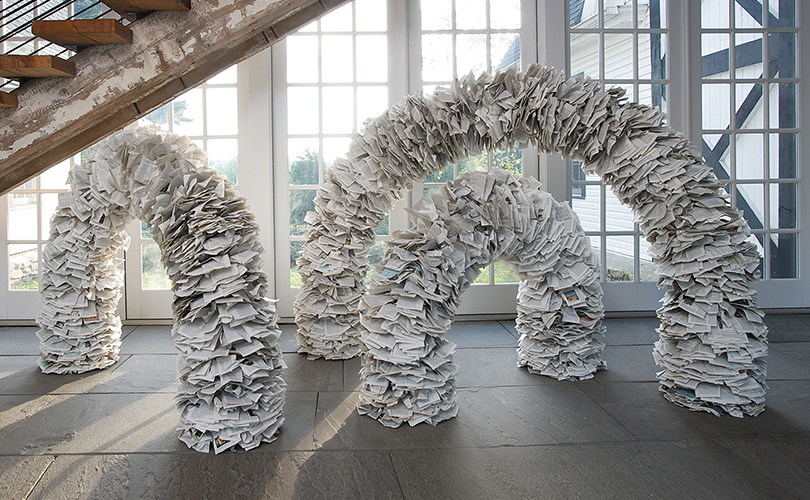

On another trip to the highland communities, that are about 3000 meters above sea level, we found imagined evidences of giant’s existence in the Venezuelan Andes, a new trace for reflection and work in the future.

We continue working, traveling and interacting with the people that surround us. Our world is here, in these mountains, in small spaces, they are safe territories which help us to create, to build deep interconnections with life, family, friends and nature giving us the guidelines to follow in the midst of turbulence and changes.”