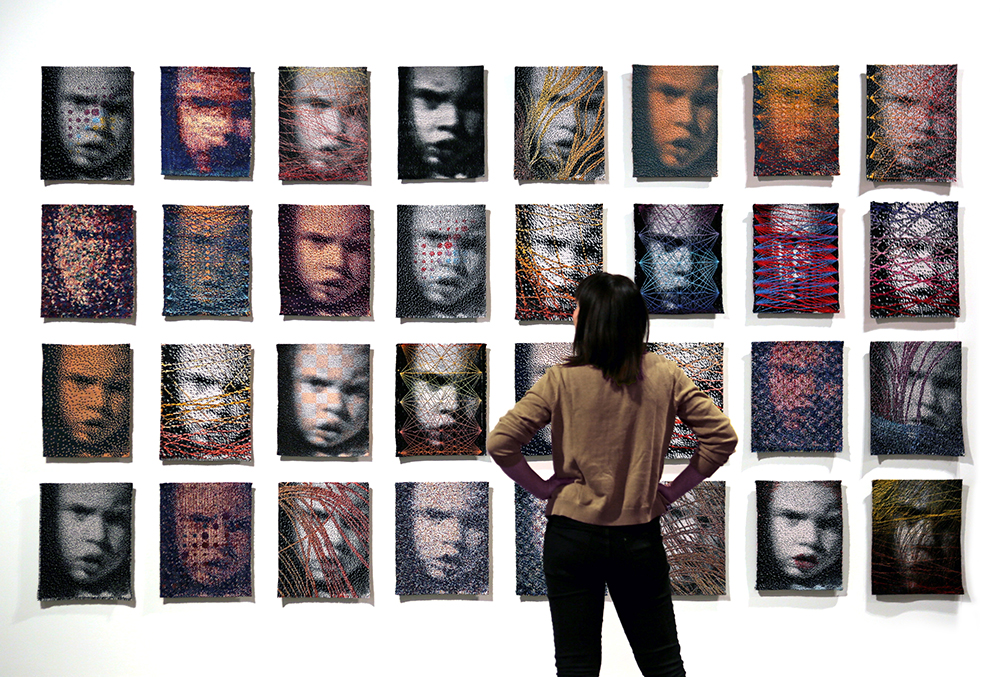

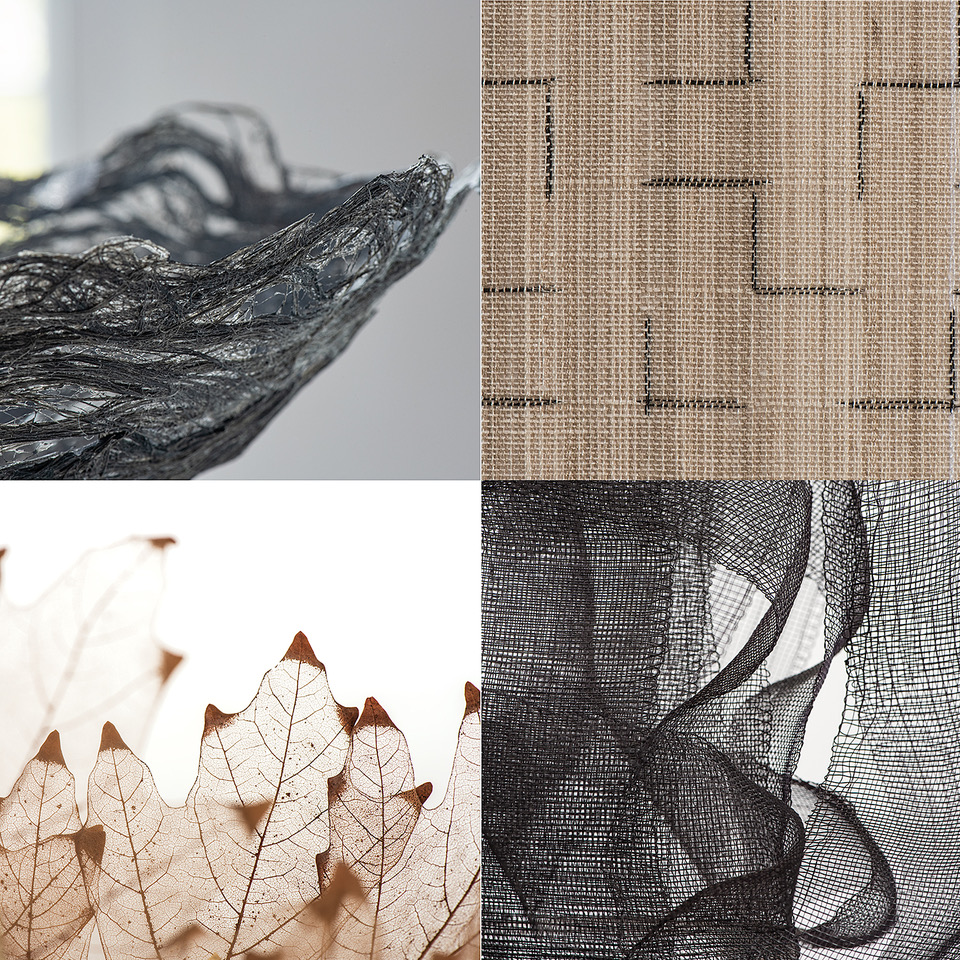

At browngrotta arts, we are delighted to exhibiting the work of consummate innovator James Bassler in Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber Art for Three Decades. For decades he has applied ancient techniques and materials to create works with contemporary themes. As Joyce Lovelace wrote in American Craft in 2011, “Few have lived life as happily steeped in materials and handwork as James Bassler, textile artist and professor. Bassler is a maker to his core, as evidenced by his extraordinary art tapestries, prized by collectors, and his eloquence on the subject of craft – down to the charming, unconscious way he peppers conversation with phrases like ‘weave that in’ and ‘grasping at straws.’”

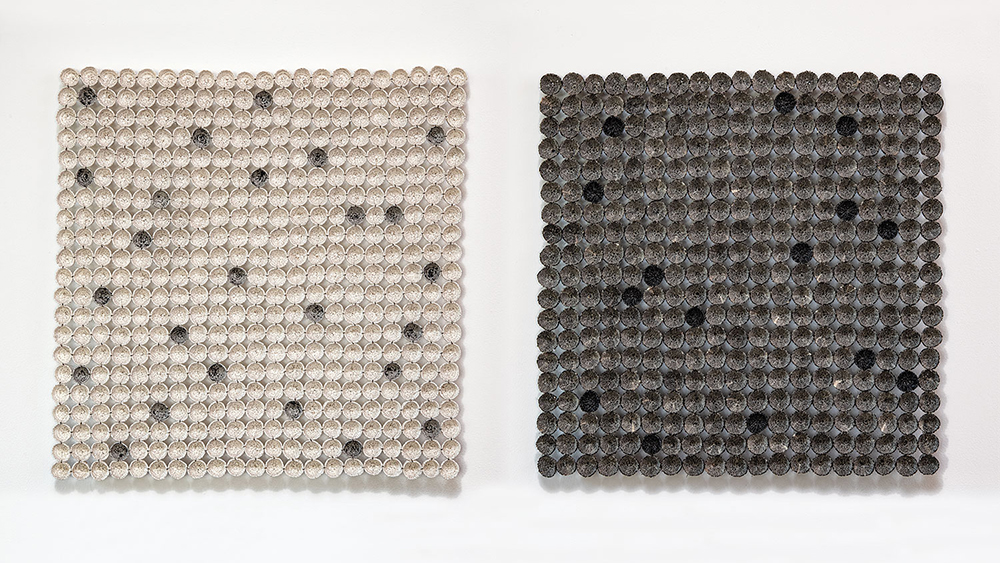

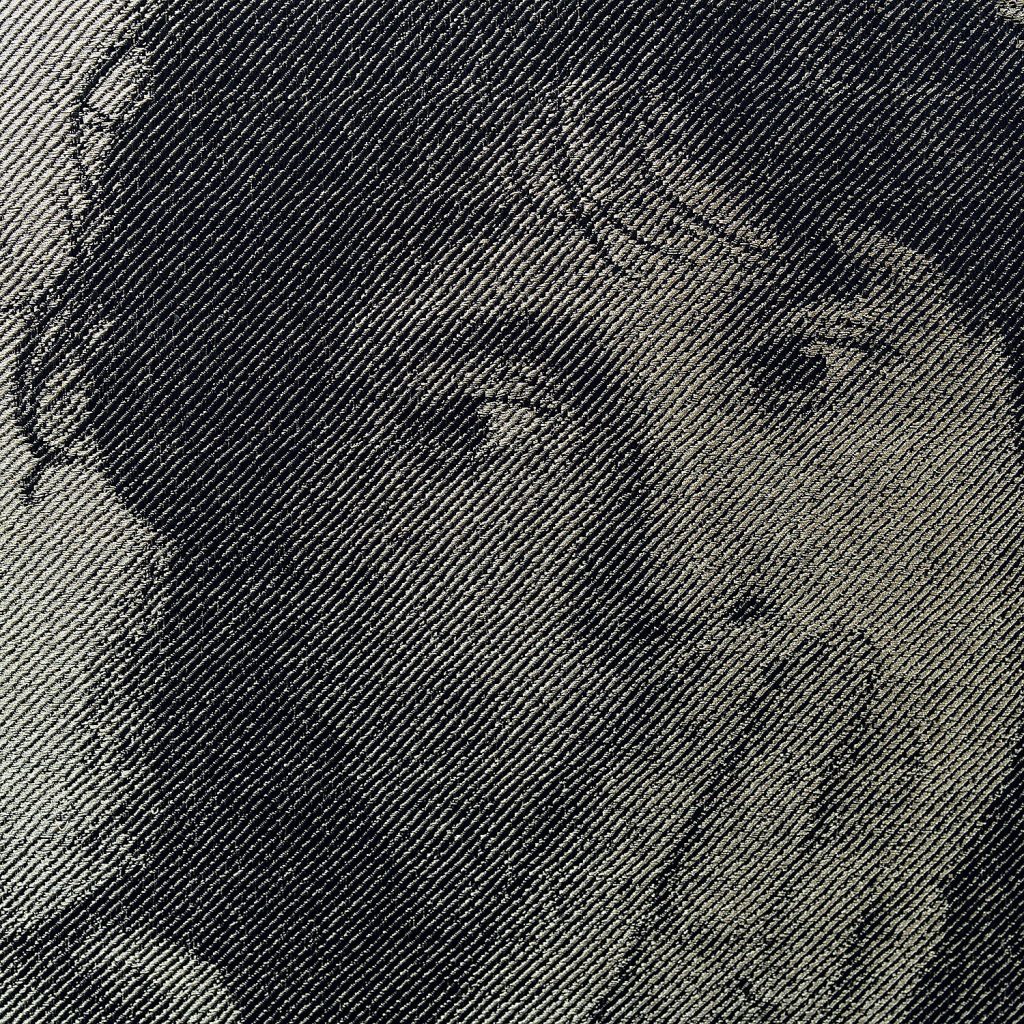

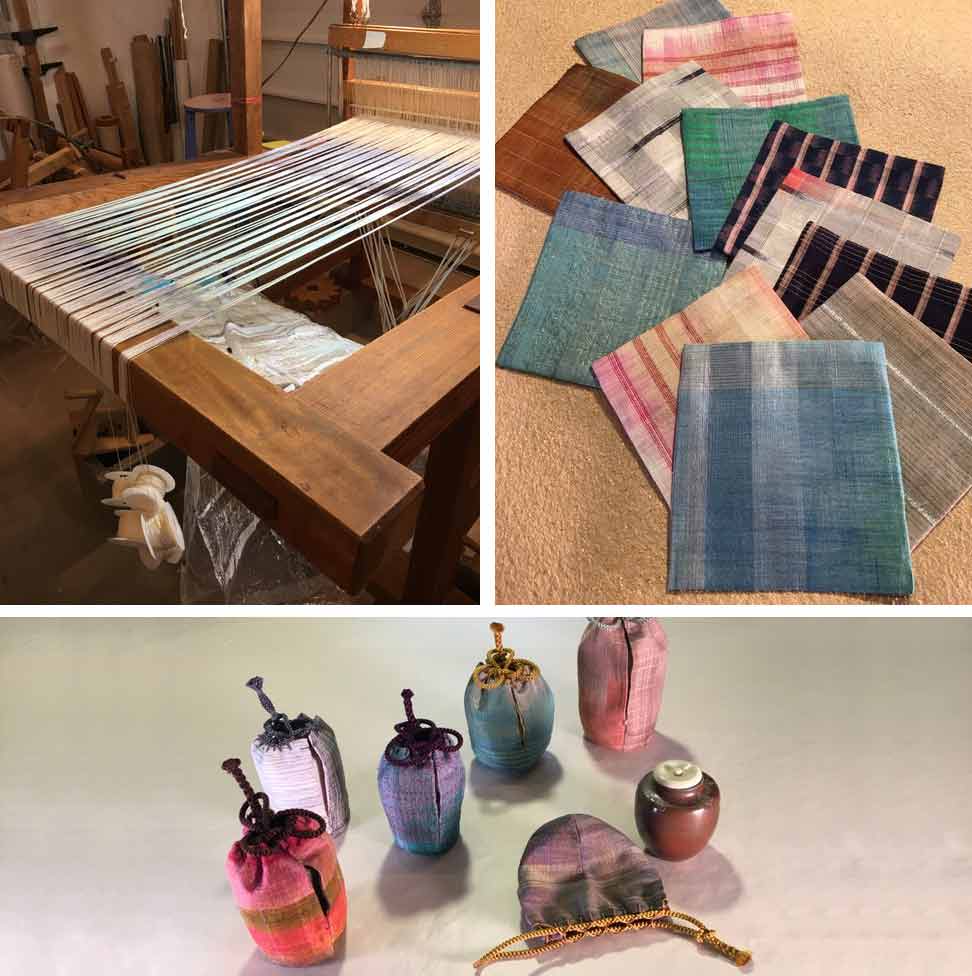

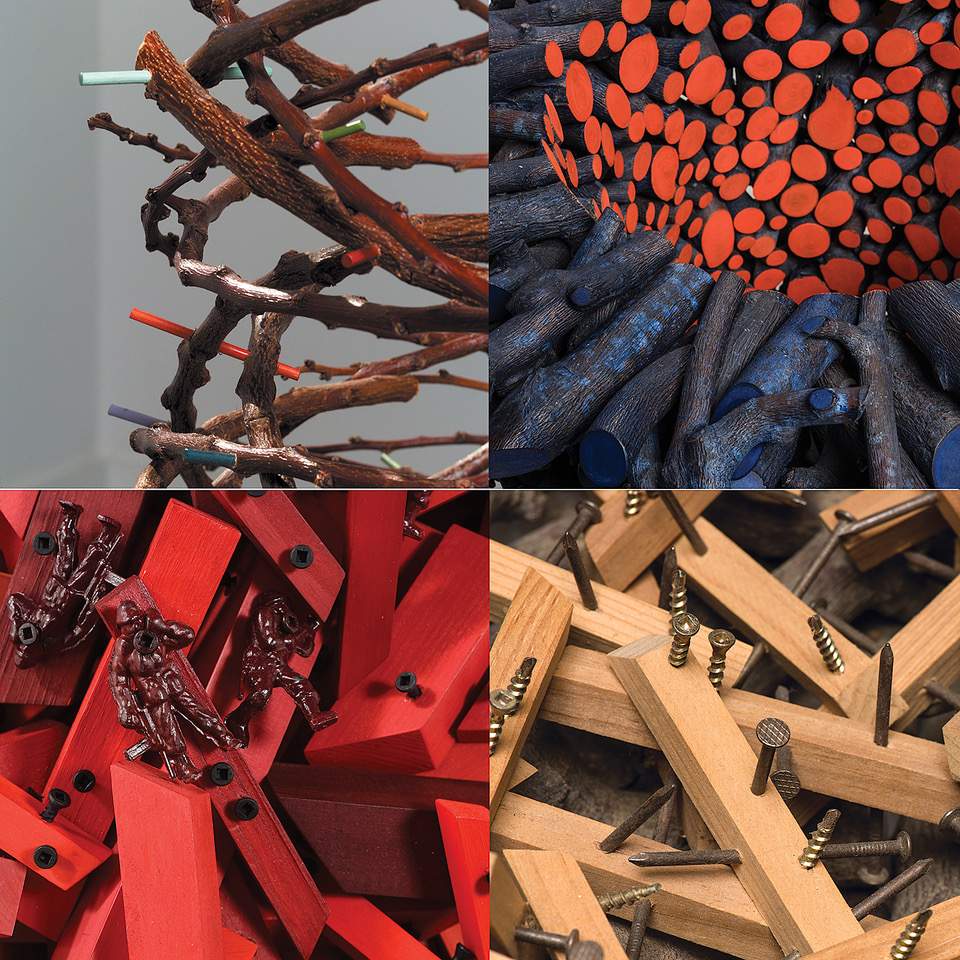

For decades Bassler has applied ancient techniques and materials to create works with contemporary themes. Bassler is prolific and we have several examples of his work inhouse that we’ll be sharing throughout the year. For Volume 50, we are exhibiting a tapestry, Weaving with Coyuchi, made with coyuche, handspun brown cotton, using a wedge-weave technique, practiced by, among others, the Navajo in the 1880s. To make Weaving with Coyuchi, Bassler first ran an image of a weaving through a printing press and then enlarged that image on a photocopy machine. After that, “All I had to do,” he said, “was weave it.” We’ll also be including a sculpture, Shop. Made from Trader Joe’s bags spun into thread to make bag from bags, Shop offers a wry statement about materials and materialism.

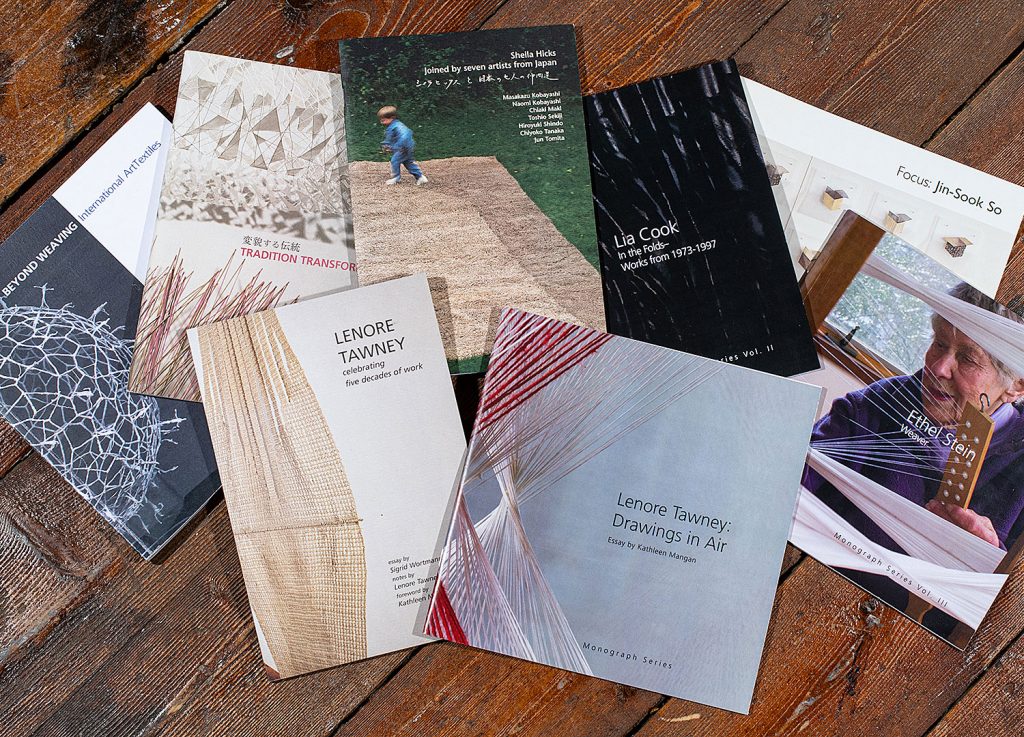

Following military service in Europe, Bassler traveled through the Middle East and Asia in the 1950s — steeping himself in traditional crafts as he traveled. traditional crafts he saw. After earning a teaching degree in the US, he and his wife, Veralee, a ceramist, moved to Oaxaca, Mexico, where they ran a craft school. In 1975, he joined the art faculty at UCLA and taught textile art there until his retirement in 2000. He was named to the American Craft Council College of Fellows in 1998. His work is found in numerous permanent collections including: the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, the Cleveland Art Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota and LongHouse Reserve, New York, NY.

Come see Bassler’s work and that of 60+ other artists at Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber Art for Three Decades from September 12-20 at browngrotta arts, 276 Ridgefield Road, Wilton, Connecticut: Opening and Reception: Saturday, September 12th, 1:00 – 6:30 pm, Daily Exhibition Hours: September 13th – 20th, 10:00 am – 5:00 pm.

Save Viewing Information: Please note that advanced time reservations are mandatory to view the show. We have worked hard to plan this event with your health and safety in mind. To ensure the well being of all visitors and staff, there will be a maximum capacity of 15 visitors per time slot and wil operate in accordance with safety and social distancing guidelines. All surfaces will be disinfected between reservations. Masks will be required.

If you have any questions or concerns regarding our policy for the show or reservations, please reach out to us at: art@browngrotta.com or 203.834.0623.