This week we share another testament to the profound influence that John McQueen has had within the art world. The recollection below is from Hideko Numata, the curator of the influential exhibitions Weaving the World: the Art of Linear Construction at the Yokohama Museum of Art in Japan in 1999.

Last month, I received the deeply saddening news from Hisako Sekijima that John McQueen had passed away. I was filled with a profound sense of sorrow and regret. Meeting John McQueen remains one of the most meaningful and unforgettable experiences of my career as a curator.

I first encountered John McQueen around 1997, while I was planning the 10th-anniversary exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art. I was responsible for the crafts section. At that time, I had the uncomfortable sense that there was a noticeable divide between fine art and crafts in the Japanese art world. Even in our museum, which focused on modern and contemporary art, the crafts section was often undervalued, and I frequently found myself frustrated by these limitations. I began to wonder whether it might be possible to curate an exhibition that transcended traditional art categories and explored the origins of artistic formation.

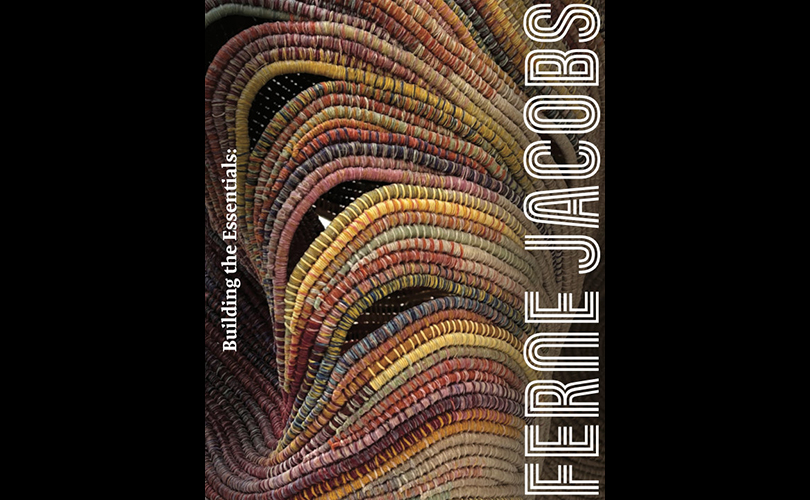

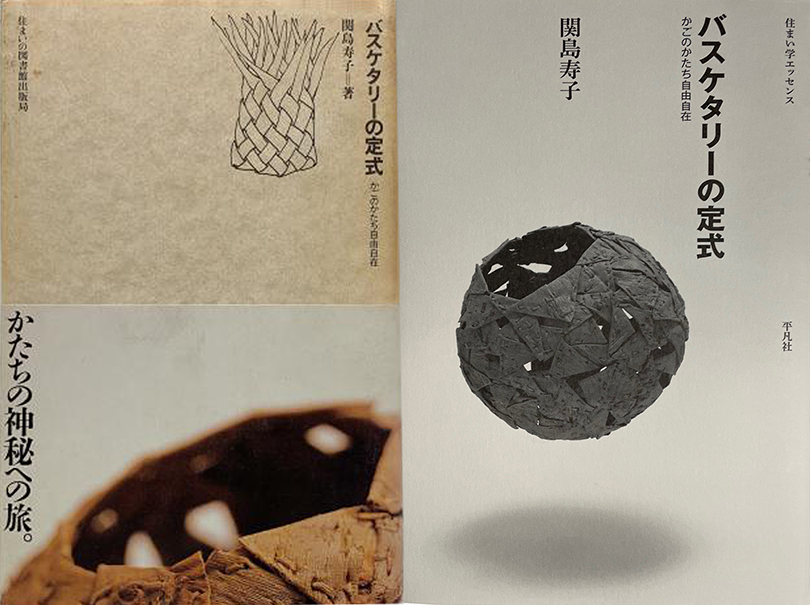

It was during this period that I came across Hisako Sekijima’s book, The Formula of Basketry. Although Japan has a longstanding tradition of bamboo craft, her book transformed my understanding of basketry—not simply as the weaving of plant materials into containers, but as a medium of dynamic expression with limitless potential. Basketry, I realized, could incorporate not only natural elements but also paper, wire, and other materials, to create both flat and sculptural forms from linear elements.

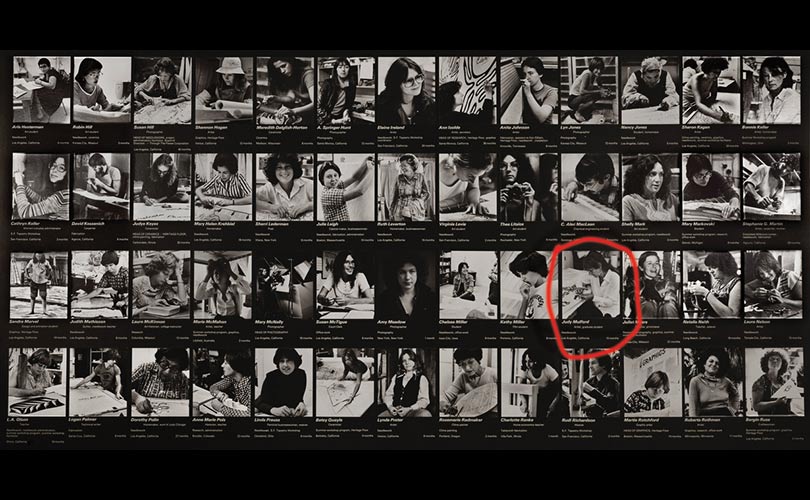

Hisako Sekijima began making baskets in Japan, but her time in the United States from 1975 to 1979 exposed her to basketry as an art form. She was captivated by the spirit of freedom and experimentation she found there. Participating in John McQueen’s workshop during that period was a turning point for her. Her vivid recollections in the book sparked my own interest in both McQueen’s work and the artist himself.

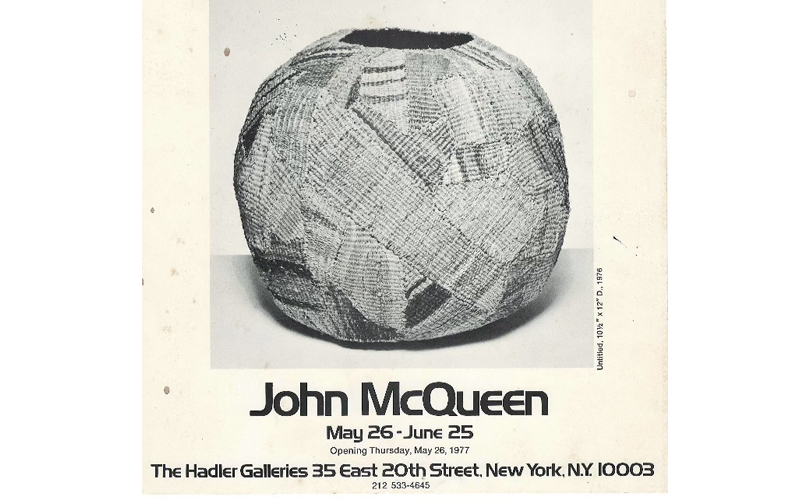

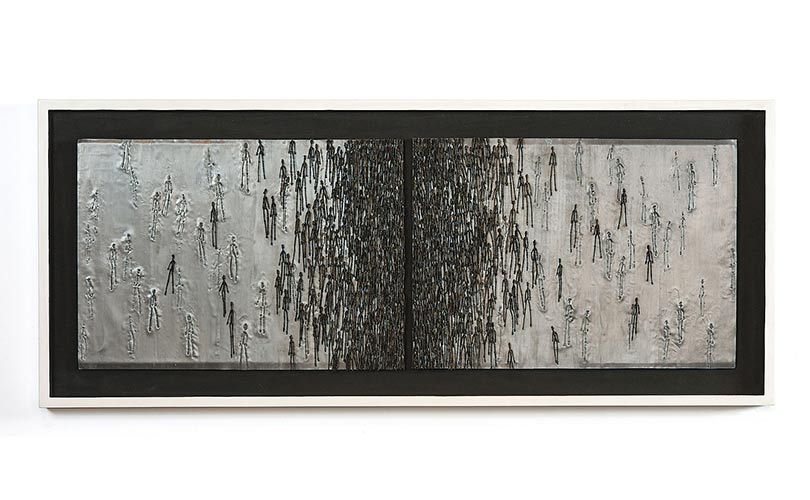

When I first encountered his art, I was immediately struck by its originality. McQueen used a wide range of materials and weaving techniques to create abstract forms, alphabetic characters, and large-scale figures of people and animals. His works were not functional baskets but powerful sculptures—three-dimensional expressions of contemporary art. The materials and weaving methods themselves appeared to alter the forms and movements they expressed. They overturned my preconceived notions of sculpture.

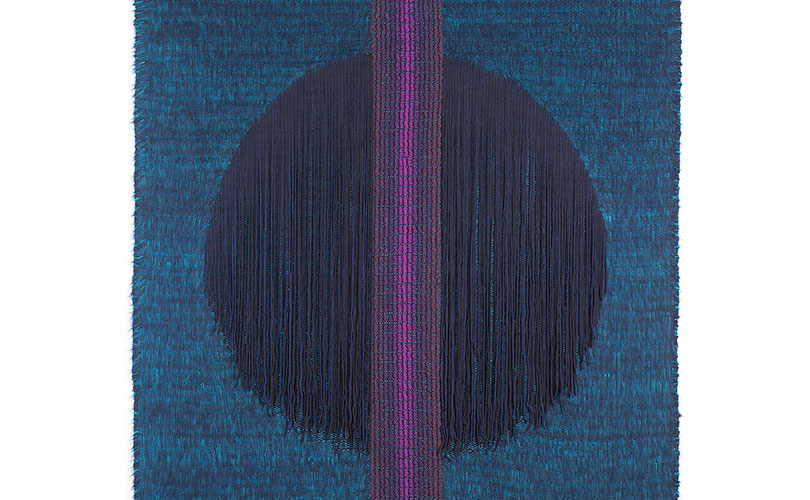

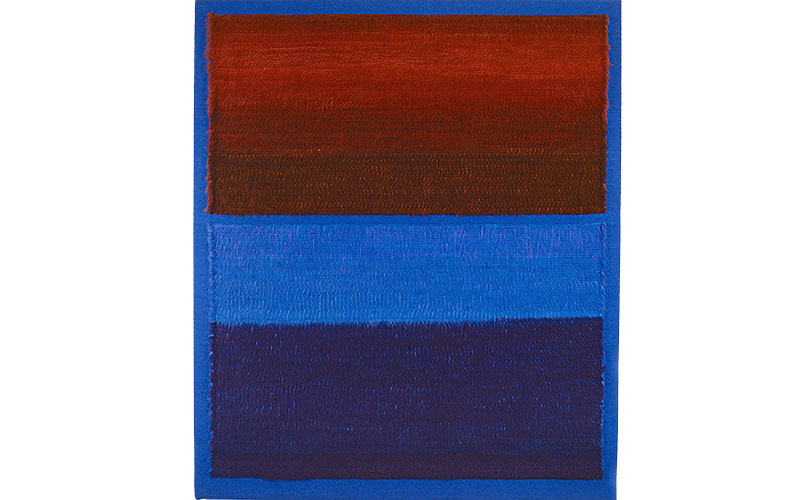

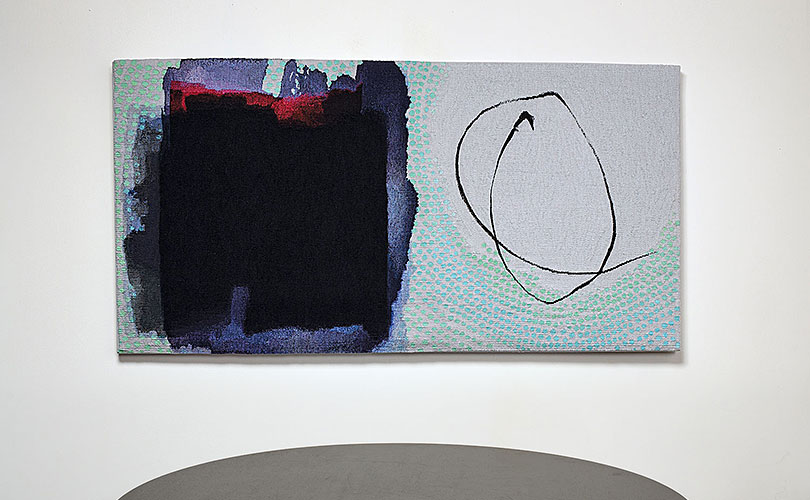

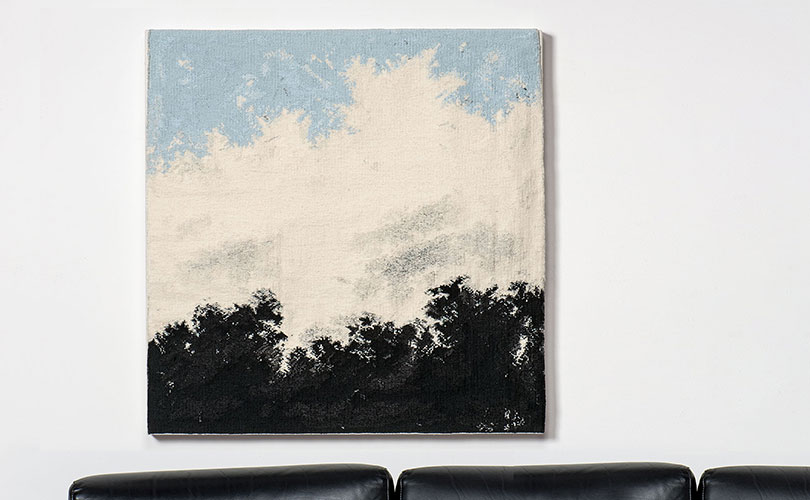

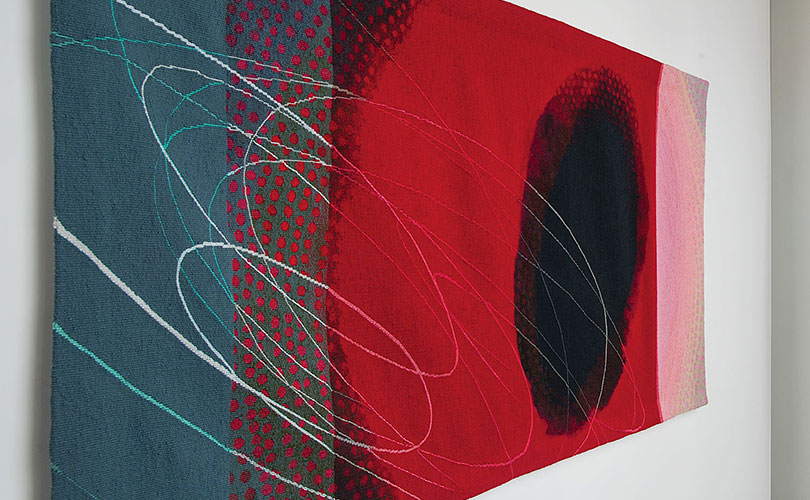

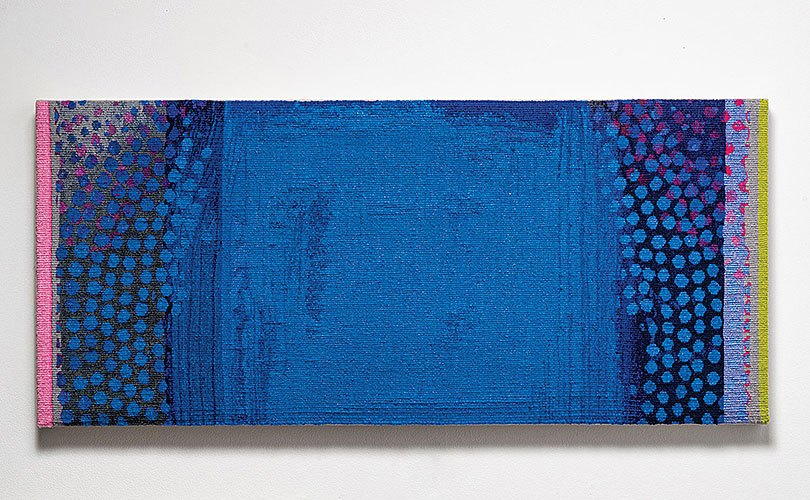

The act of weaving — strands forming two- or three-dimensional shapes — is one of the most fundamental, universal methods of making. Practiced globally since ancient times, it holds an infinite capacity for expression. I felt it could offer a way to bridge the gap between fine art and craft. This realization led me to curate the exhibition Weaving the World, Contemporary Art of Linear Construction, which brought together works from both craft fields such as basketry and textiles, and contemporary art that used linear or woven elements.

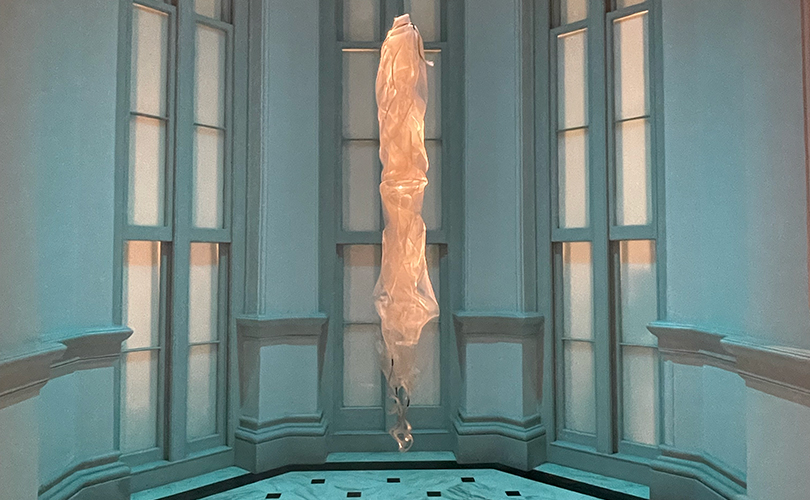

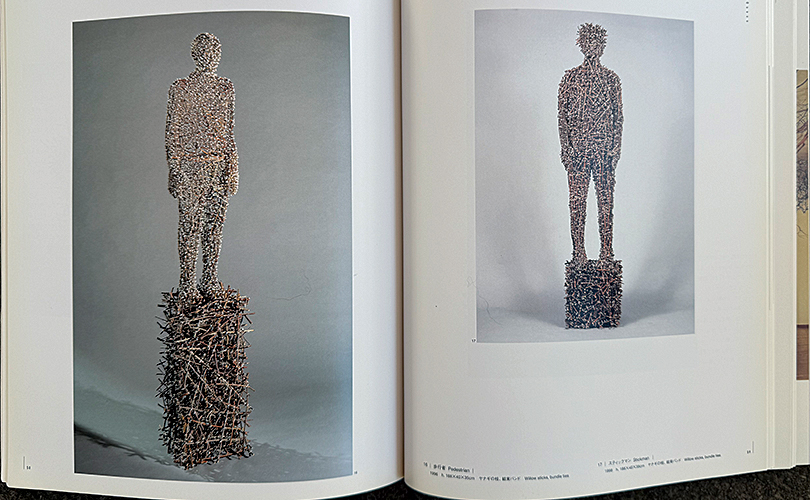

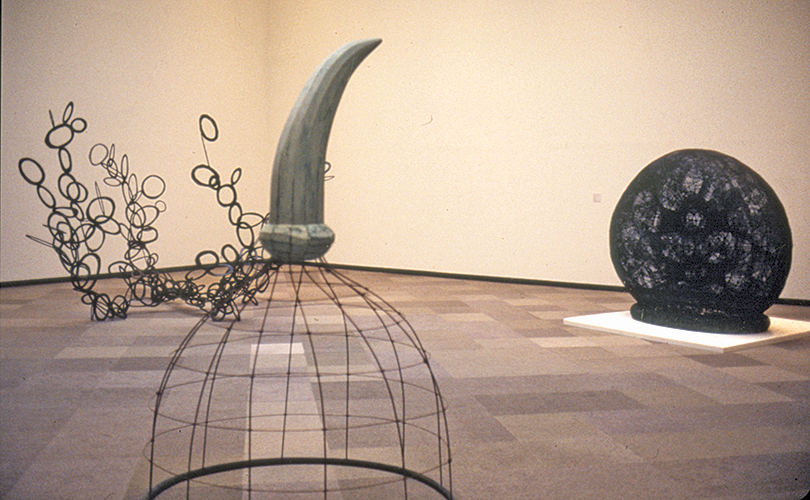

For this exhibition, John McQueen contributed one bird’s nest-like piece and two human-shaped sculptures. The bird’s nest-like structure was constructed from short wooden branches inserted and layered to form a structure that, while sturdy, appeared almost fragile—like it might collapse at any moment. The human figures were created using branches and vines secured with plastic cable ties. One figure was made by weaving taut, slender vines into an airy yet resilient human shape. It maintained a strong presence, offering glimpses through its woven mesh to the inner space and the world beyond. The other was composed by densely interweaving branches to fill the interior form. Although it was structurally solid, it lacked the gravitas of stone or bronze, instead possessing a lighthearted, even humorous character. McQueen’s work effortlessly transcended the boundaries between sculpture and craft.

The exhibition featured artists from Europe, the United States, and Japan, spanning both the craft and contemporary art worlds. These included browngrotta arts gallery artists such as Norma Minkowitz, Markku Kosonen, Toshio Sekiji, and Hisako Sekijima; sculptors like Richard Deacon and Martin Puryear; installation artists working with natural materials, including Andy Goldsworthy and Ludwika Ogorzelec; Supports/Surfaces artists like François Rouan; and conceptual artists such as Rosemarie Trockel and Margo Mensing. Though diverse in practice, they were united in their exploration of “line” as a medium – unfolding into inner landscapes, social commentary, and artistic forms Viewers could deeply appreciate the richness of art created by weaving linear materials as they moved through the exhibition space.

During the exhibition, we held a three-day public workshop titled “Weaving Yokohama, Crossing Paths” led by John McQueen and Margo Mensing. Takahiro Kinoshita, an educator of the Yokohama Museum of Art’s education group, organized this workshop. He spent an entire year coordinating the event with the two artists. Fifty participants and twenty-three volunteers took part. On the first day, there was an introduction to the workshop, consecutive lectures from McQueen, Mensing, and Sekijima. The following two days were dedicated to creation, taking place in the museum’s open-air portico, where the public could observe the process.

The workshop used bottom trawl nets previously employed by Yokohama’s fishermen. Working in pairs, participants traced human shapes onto the nets, cut them out, and wove various materials into the forms. On the first day, they completed the human-shaped silhouettes. The second day focused on filling the interior spaces by weaving in different materials. Though more challenging than expected, the collaborative process allowed each pair to create a unique piece through trial, connection, and creativity. Even beginners were able to experience the satisfaction of shaping and completing something with their own hands. Each work reflected its creators—different in material, method, and spirit—shining with individuality.

The exhibition and workshop were warmly received by the public, and the exhibition was honored with that year’s Ringa Award for the outstanding exhibition that year. I believe that by focusing on the elemental act of weaving, visitors were able to rediscover the joy of form-making and expression—beyond the confines of any genre.

I remain deeply grateful to John McQueen. He reminded me that even the most humble materials and methods can give rise to profound beauty and meaning. His inspiration continues to live on, not only in his works but in all of us who had the honor of working with him.

May he rest in peace.

Hideko Numata

Professor, Showa University of Music

Former Chief Curator of the Yokohama Museum of Art Curator,

Weaving the World: Contemporary Art of Linear Construction,

Yokohama Museum of Art, Japan 1999