Rhonda Brown

Dorothy Liebes (1897 – 1972) was an influencer before the term was coined. Known as the “mother of modern weaving,” and initiator of “The Liebes Look” she served as a national arbiter of interior design and fashion trends reaching thousands of people through print magazines, television, film, and significant collaborations with architects and corporations from Frank Lloyd Wright to Dupont. Liebes created luminous, jewel-toned fabrics, often incorporating nontraditional materials and metallic threads.

Her influence extended well beyond influencing consumer trends. She impacted the careers of numerous artists – some who only met her and studied her work and others who worked in her studios in San Francisco and New York.

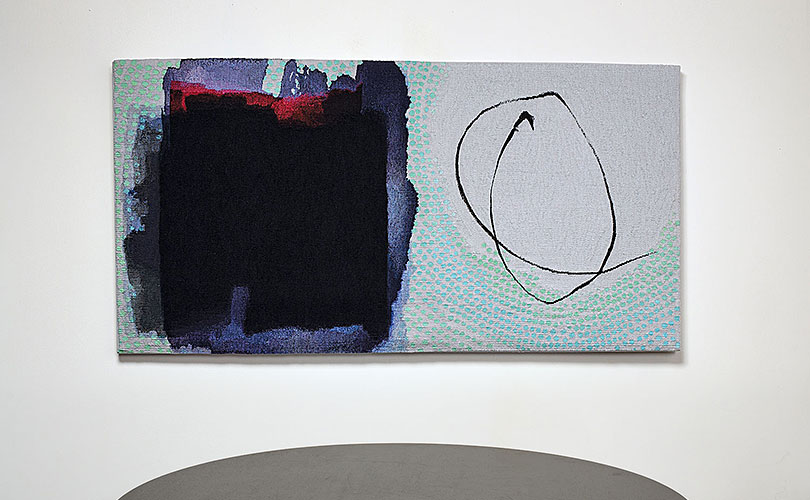

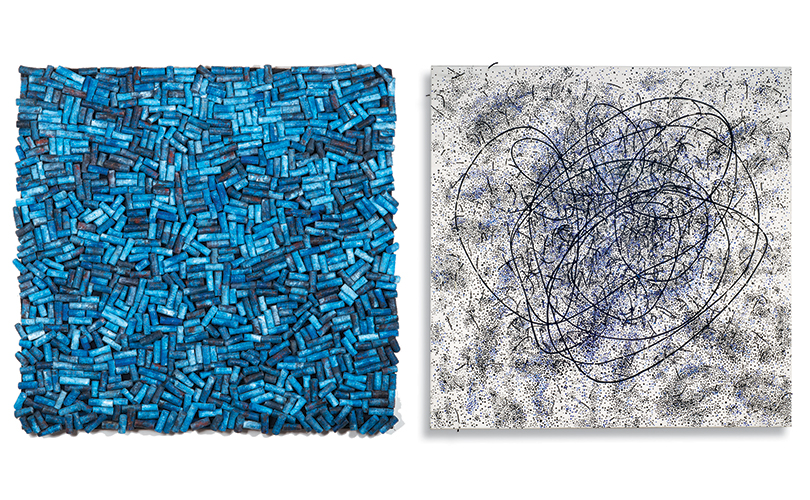

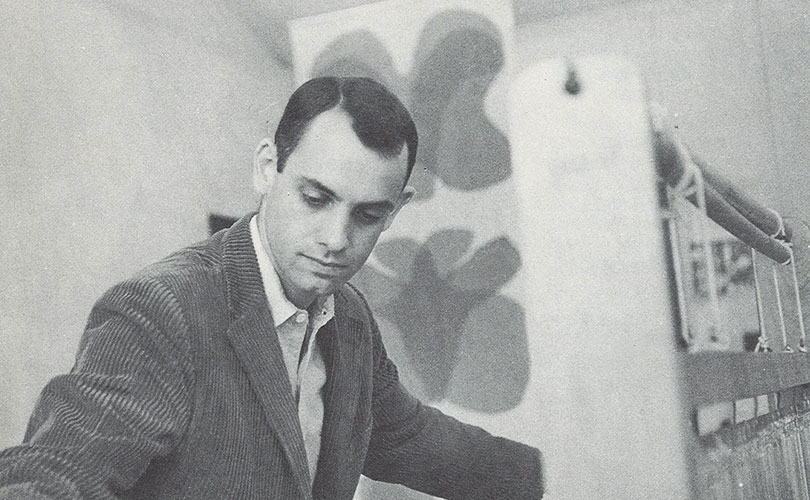

Ed Rossbach met Dorothy Liebes only in passing, but her influence on his work was marked. In 1940, after he had finished college, he visited an International Exposition at Treasure Island in California and saw the decorative arts exhibit that Dorothy Lieber had installed there. “I didn’t know anything about Dorothy Liebes, naturally,” he told Harriet Nathan in 1983. (Charles Edmund Rossbach, “Artist, Mentor, Professor, Writer,” an oral history conducted in 1983 by Harriet Nathan, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1987, p. 14.) “I saw these contemporary textiles and weavings and wrote in my diary that I would like to learn how to weave so that I could weave upholstery.” Years later, when Rossbach had moved to the Bay Area, he visited Liebes’s studio. He recounted being awestruck by the things she inserted into her warp, by her whole personality, and how she interacted with those who worked for her. (Lia Cook, “Ed Rossbach: Educator,” in Ed Rossbach: 40 Years of Exploration and Innovation in Fiber Art, Lark Books and Textile Museum, 1990.) Liebes “had a sense of [her] own importance,” he said later, in an interview with the Archives of American Art. (Oral history interview with Ed Rossbach, 2002 August 27-29. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.) Like Liebes, Rossbach would become known for incorporating non-traditional materials into his work.

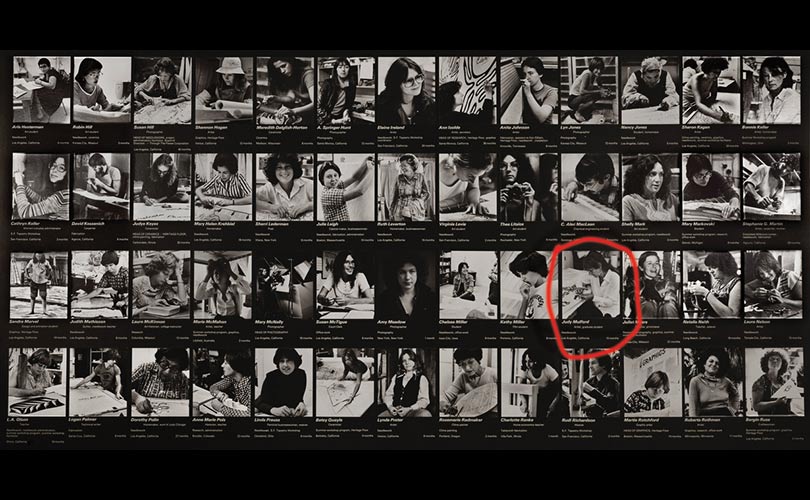

Three other artists whose work is shown by browngrotta arts in Wilton, Connecticut – Sherri Smith, Glen Kaufman, and Mariette Rousseau-Vermette — were among Liebes’s studio alumni — their experiences with the designer were evident throughout their artistic careers

Artist and educator, Sherri Smith, went to work in Dorothy Liebes’s studio after she completed MFA in weaving and textile design at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in 1967. From there she went to Boris Knoll Fabrics, where she headed the Woven Design Department. Smith was well situated for her first major museum success — the inclusion of her piece Volcano No. 10, 1967 in MoMA’s Wall Hangings curated by Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenor Larsen in 1969.

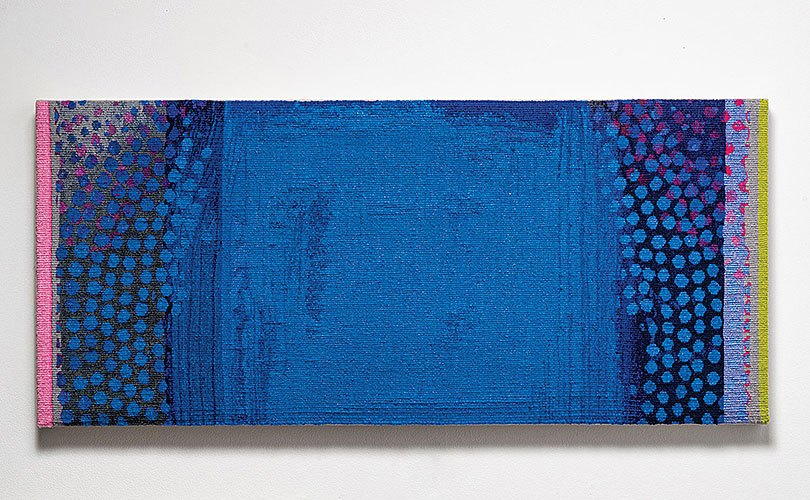

Glen Kaufman spent a year at Liebes’s New York studio from 1960 to 1961, after a Fulbright in Scandinavia. Kaufman was also a Cranbrook graduate. There he created handwoven pile rugs among other items. At the Liebes studio, he and Harry Soviak, a Cranbrook classmate, concentrated on carpet designs and created pillows in “wild colors.” The pair would try to “out-Dorothy Dorothy Liebes,” making pillows using Liebes’s daring color combinations and metallic yarn, Kaufman told Josephine Shea in an oral interview in 2008. He recalled that the designer “had this reputation of being the arbiter of interior taste. And she would put together things like red and pink and orange, which were absolutely out in left field,…” (FN4 Oral history interview with Glen Kaufman, 2008 January 22-February 23, Josephine Shea.)

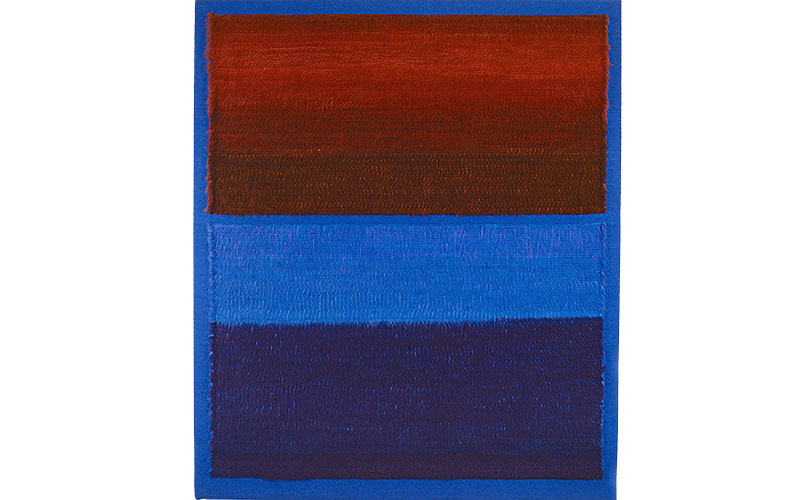

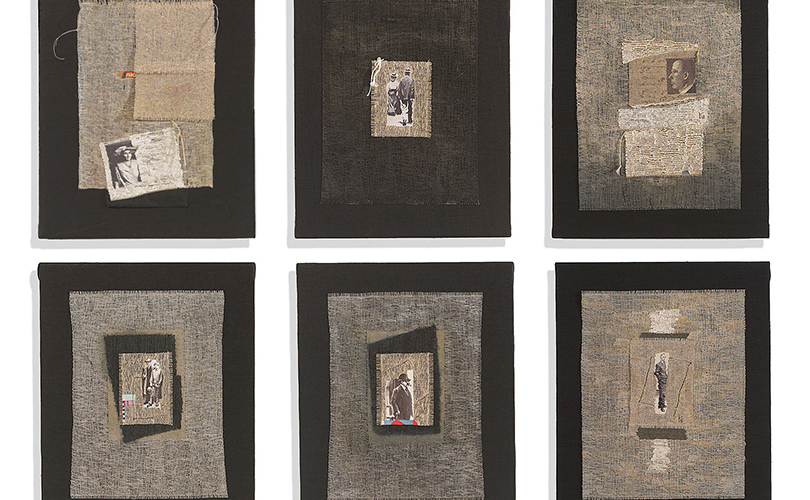

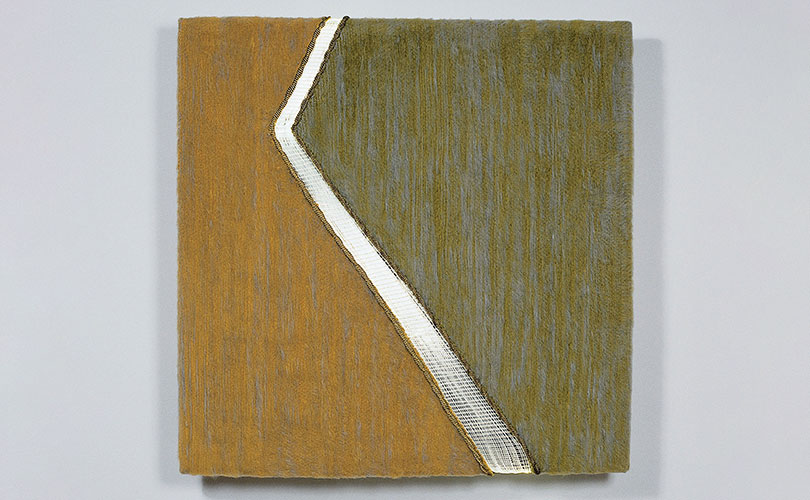

Kaufman’s work from the early 60s like Banner, paired vibrant colors. In others, like Herringbone, Odd Man In and Polymaze, Kaufman continued to explore carpet making techniques. Over time, however, he adopted a more muted palette. Liebes remained enthusiastic but bemoaned the color change. In her essay for Cooper Hewitt exhibition on Liebes and her legacy, Erin Dowding quotes a 1967 letter from Liebes to Kaufman in which the designer writes about seeing his works, “which I thought were wonderful. I missed color, though, and I’m sure you do too.” (Glen Kaufman essay by Erin Dowding, Cooper Hewitt Museum).

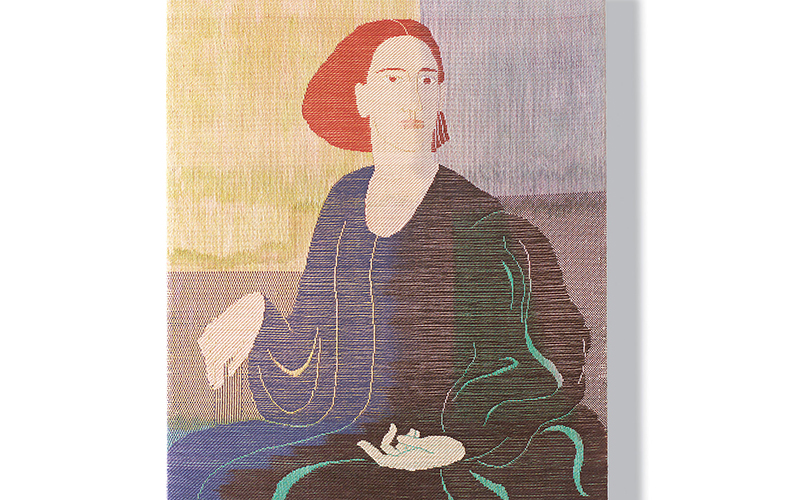

Mariette Rousseau-Vermette’s experience with Dorothy Liebes was perhaps the most formative. The details of the year she worked in Lieben’s California studio have been compiled and generously shared with us by Anne Newlands. Newlands is the author of Weaving Modernist Art: the Life and Work of Mariette Rousseau-Vermette and the guest curator of an upcoming retrospective of Rousseau-Vermette’s work at the Musée National des Beaux-arts du Quebec in Quebec City in 2025.

After graduation from the École des beaux-arts in Montreal in 1948, Mariette, then Rousseau, later Rousseau-Vermette, looked to the United States to further her education, unlike fellow students who travelled to France. She was inspired by a 1947 issue of Life magazine in which an article titled “Top Weaver” introduced her to the innovative Dorothy Liebes studio in San Francisco. Years later, she described the impact: “The article blew me away — this magnificent woman was radically changing textiles in the United States, she was returning them to art. For her, textures, colours, techniques had no limits.” (Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, public lecture, Musée du Québec, 23 August 1992. Translation by Judith Terry. Cited Anne Newlands.) In addition to Liebes’s innovations with non-traditional weaving materials, Rousseau-Vermette said she was captivated by Liebes’s “prophetic instinct for trends in color.”

After graduation, despite the fact that she spoke little English at the time, Rousseau traveled to San Francisco for two reasons: to secure a job or an internship at the Liebes studio and to study at the California College of Arts and Crafts in nearby Oakland. Her mornings were spent at the college in Oakland, and in the afternoons she waited patiently in the reception area of the Liebes studio, her thick sample books from the École des beaux-arts on her lap, trying to convince the studio to hire her. With a determination that would become legendary, Rousseau-Vermette returned daily and finally Dorothy Liebes relented, saying that she could not pay her (although later she would), but that she would let her work. (Material on Mariette Rousseau-Vermette. Cited by Anne Newlands.) “Try — Do not be afraid — Make ‘research’ a pleasure – Share with others. These are the ‘gifts’ I received during my stay in Dorothy Liebes’s studio.” Rousseau-Vermette wrote. “At the end of the 1940s, Dorothy Liebes’s endless energy and joie de vivre, and the friendship among her thirteen assistants, started me on the path that became my way of life.” (Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, “Fiber-Optic and Other Weavings,” in Wired, browngrotta arts, 2001.)

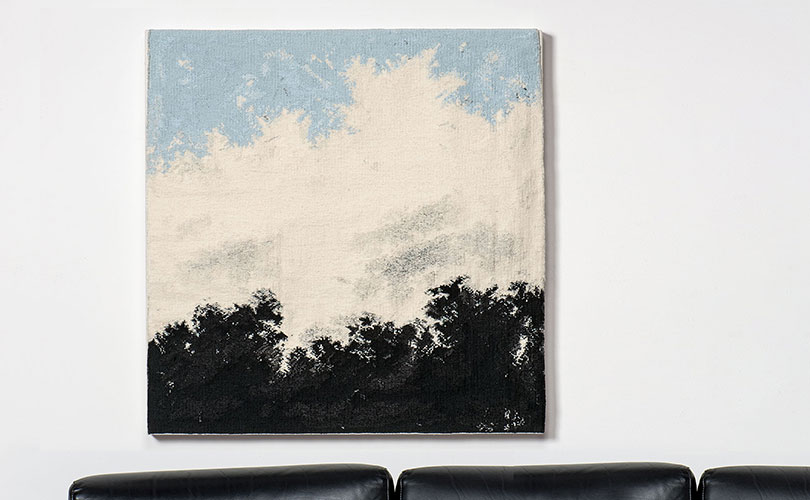

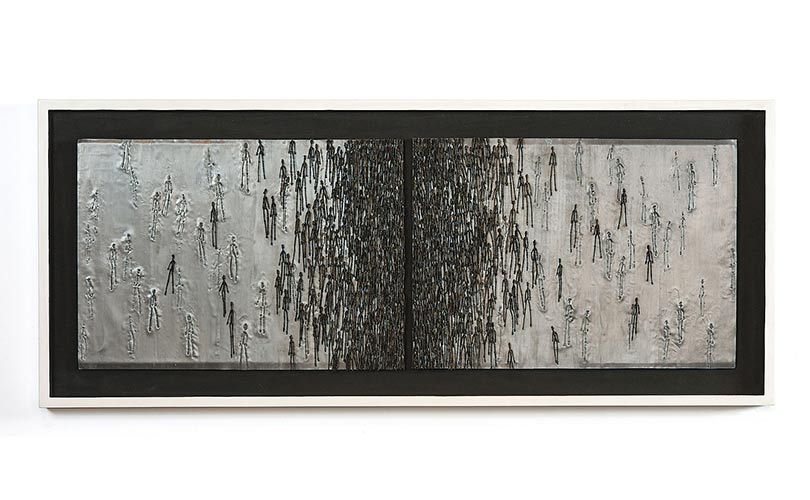

Like Liebes, much of Rousseau-Vermette’s career was devoted to creating textile works on commission to mediate architectural spaces, notably, The Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto, Exxon in New York City and Arthur Erikson’s Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto. Working with architects was central to Leibes’s practice. As Alexa Griffith Winton has noted, “Liebes encountered architectural blueprints and quickly learned to read them.” (“’None of Us is Sentimental’: About the Hand: Dorothy Liebes, Handweaving, and Design for Industry,” Alexa Griffith Winton,The Journal of Modern Craft, Volume 4—Issue 3, November 2011, pp. 255.) Rousseau would follow suit; her most preferred commissions would be those that involved collaborations with architects. Her files were thick with blueprints and architectural drawings. Where buildings were hard and cold, Liebes’s textiles were warm and soft says. Like Liebes, Rousseau-Vermette’s brilliance came from building and bridging a tension between textiles and architecture. (“How the Mother of Modern Weaving Transformed the World of Design,” Sonja Anderson, Smithsonian Magazine, July 19, 2023.)

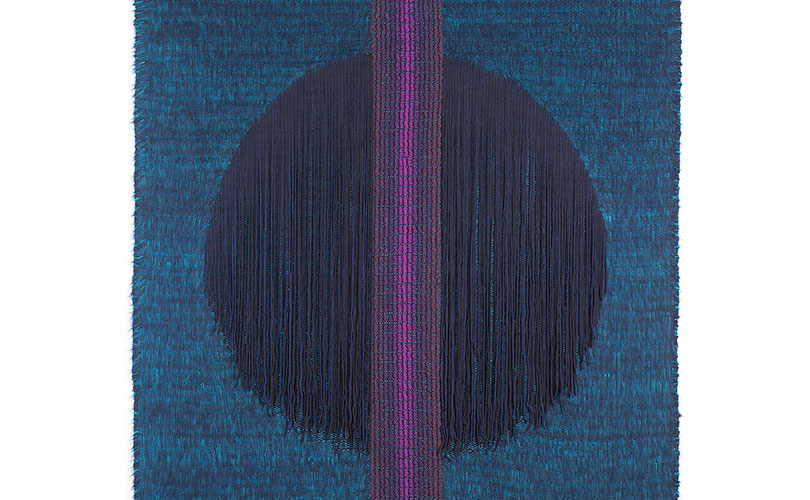

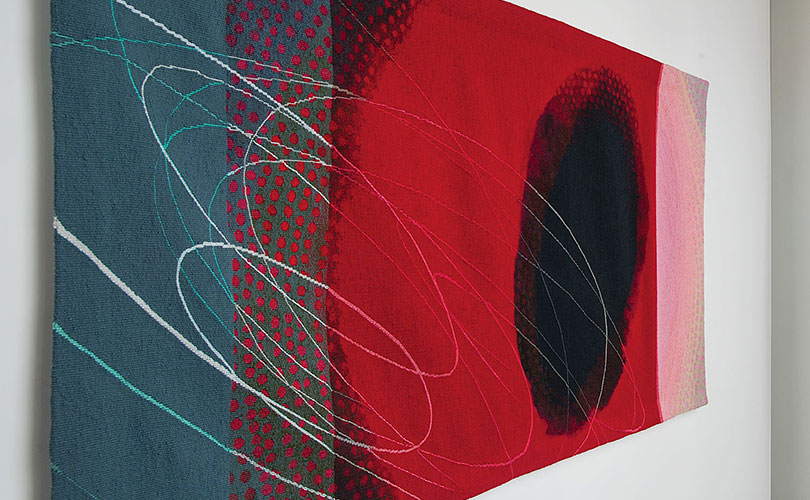

Brilliant coloration also featured in Rousseau-Vermette’s work and she utilized unique materials as Liebes’ did. Canadian architect, Arthur Erikson, wrote of a series of color fields of luscious color and texture composed vertically or horizontally of combed wool that he commissioned for a building in Vancouver, B.C. “I found the simplicity of her work blended perfectly with the simple structural expression of the building, the building transformed through the artist’s eye.” (Arthur Erickson, “Introduction,” in Wired, browngrotta arts, 2001.)

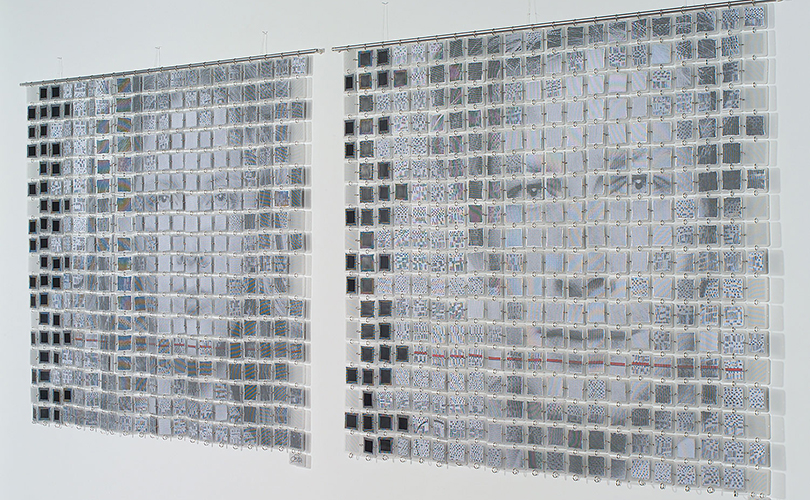

In the 1990s, Rousseau created a series innovative weavings, like Elegante, that incorporate optical fiber. Another work from 2001, Hommage á Liebes, incorporates silk, leather and fluorescent tubes, some of it material that Rousseau-Vermette had sourced from Liebes. In its title, the student explicitly credits the mentor as an impetus for her work. Liebes also influenced the way in which Rousseau-Vermette would manage her studio. Like Liebes, Rousseau-Vermette created detailed cartons and maquettes for each of the 644 tapestries she created in her career. Her meticulous notes are now in the archives of the National Gallery of Canada. She was motivated by Liebes’s success as an independent owner-operator, holding as she did a singular place in the male-dominated business world.

Want to know more? Liebes’s life and design have received renewed attention in the past year as a result of the expansive exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt in New York, with many resources available online. A lush volume accompanied the book, both entitled, A Dark, A Light, A Bright: the Designs of Dorothy Liebes.