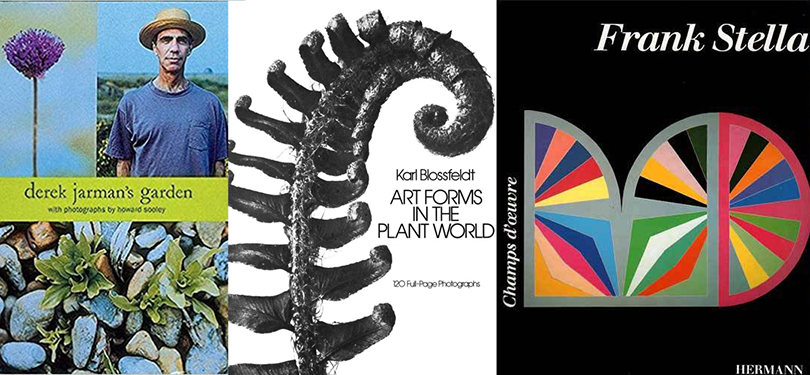

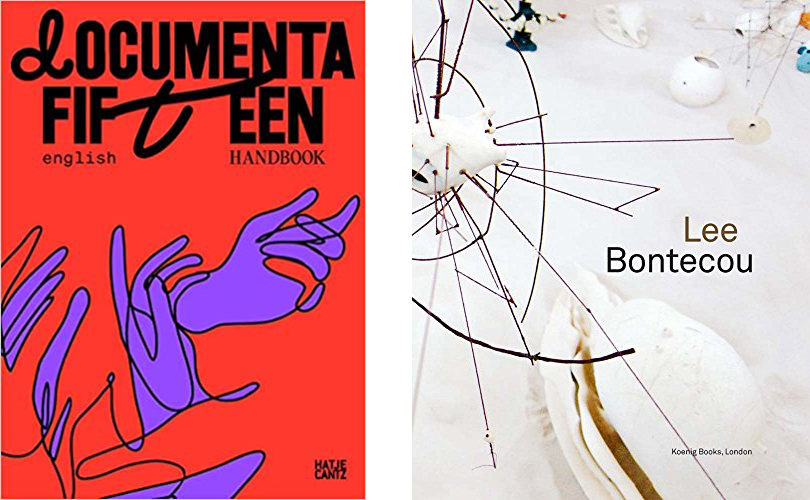

We have had a busy May. We presented Field Notes: an art survey in person at browngrotta arts in Wilton, CT and online. We have partnered with the Silvermine Art Galleries on three exhibitions that run through June 19, 2025 (IFiber 2025; Masters of the Medium: CT; Mastery and Materiality: International), and loaned several works to the thoughtfully curated exhibition WEFAN in West Cornwall, CT (through June 28, 2025). And, we highlighted a new work online in New this Week each Monday for your review.

In recapping those intriguing offerings, we begin with Keiji Nio’s captivating Cat’s Eyes. Nio is captivated by these enigmatic animals. “When I suddenly feel a gaze and turn my eyes, I sometimes find a cat staring intently at me,” he says. “Especially quiet cats, who do not meow much, whooften keep their expression unchanged, gazing without blinking, as if trying to convey something unknowable. When I return the gaze, there are moments when we slowly exchange blinks.” Nio sought to confront his memories and emotional response to cats through images he silk-screened onto aramid fabric, with which he created a wall work edged in sand.

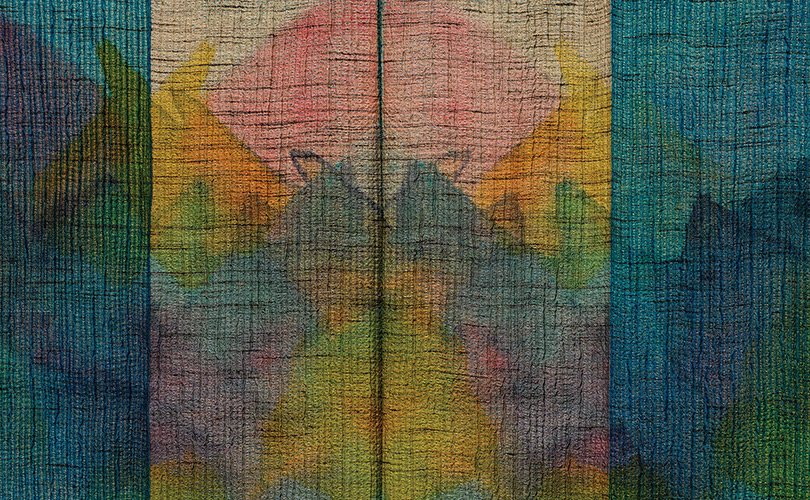

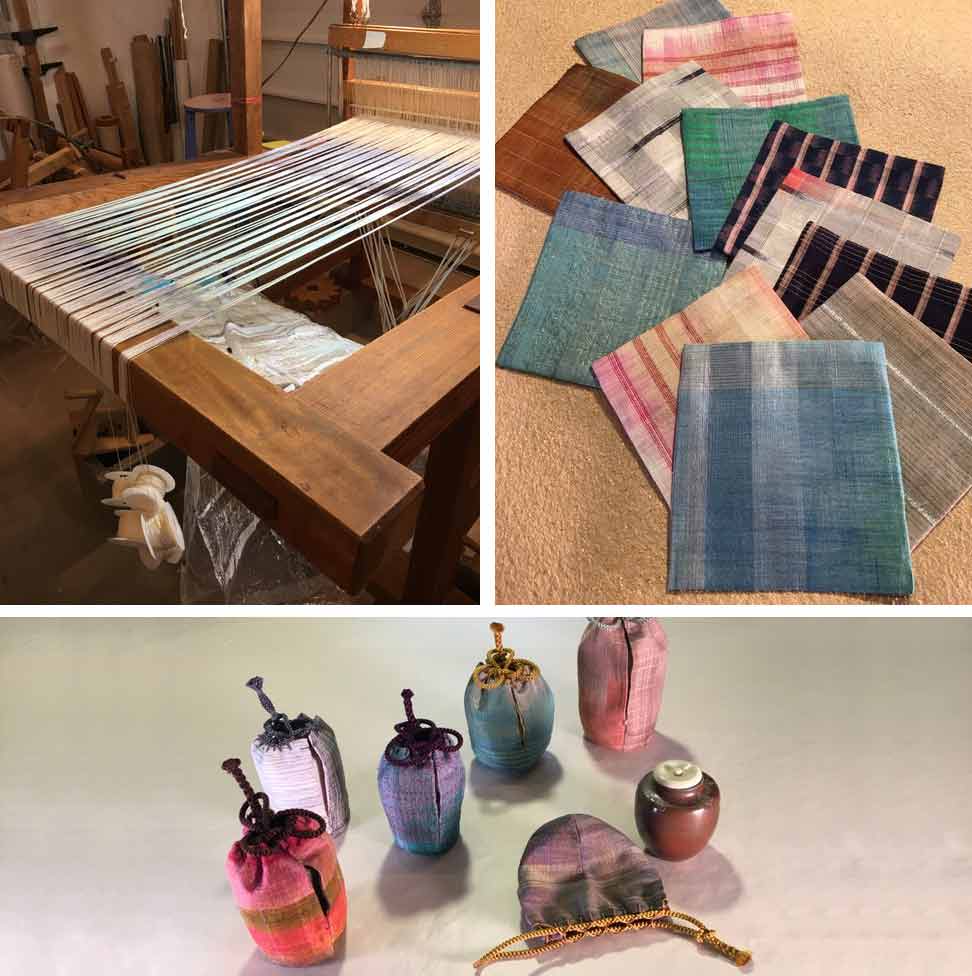

Polly Barton finds solace in following the thread, which she calls “a kind of wayfinding.” She creates a surface to rub color in a variety of forms; dye, pigment, pastel, ink. “Working at the loom where my threads are in order and my fingers work with what feels real, chaos is temporarily kept at bay,” she says. No Strings Attached began as a small watercolor sketch — a memory of petroglyphs — field notes from the past carved into basalt stones found while hiking paths in canyons. “My sketch,” she says,”like a voice from the past, beckoned to be woven as a fluid path forward into our spinning world. In my studio, Sheryl Crow sings: ‘Everyday is a winding road.I get a little bit closer … to what is really real.’

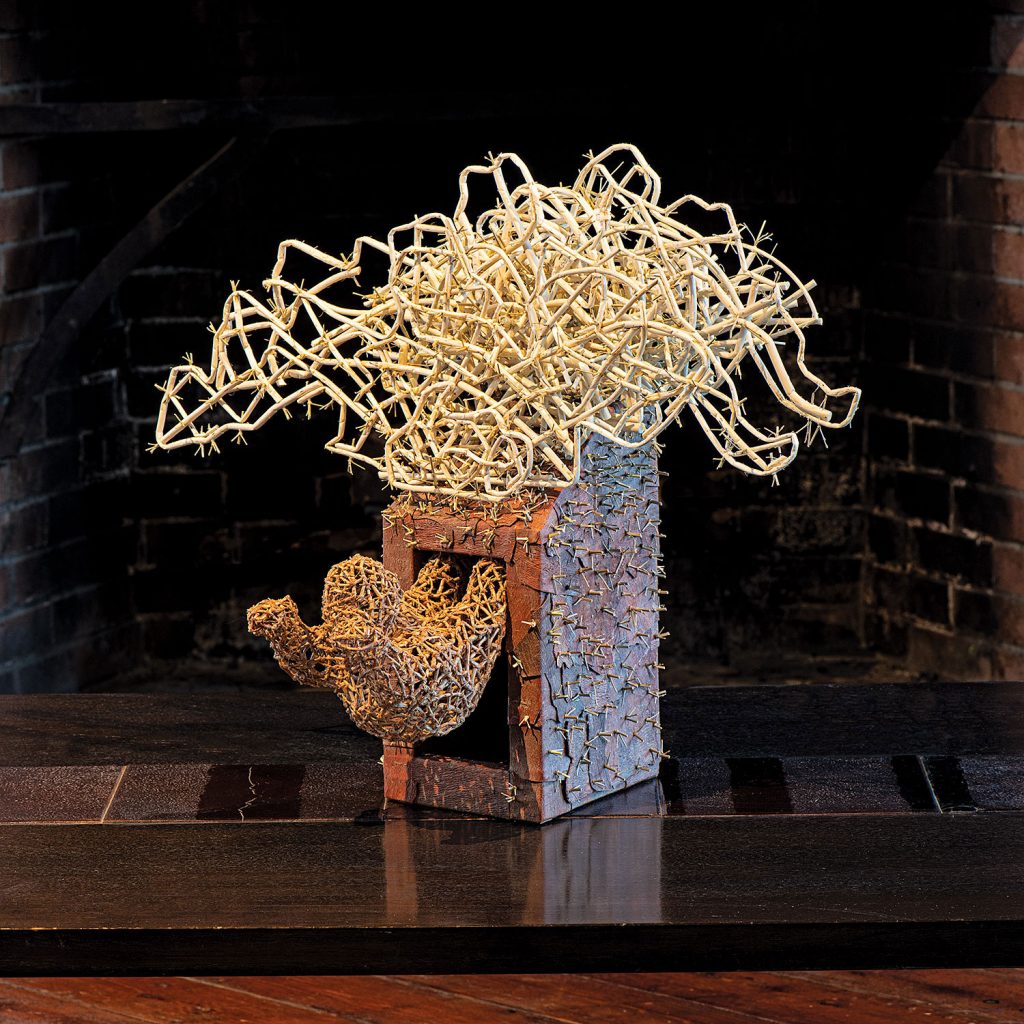

Peak in the Clouds, is the first of a short series of “landforms,” that Christine Joy started in 2022 when she was on Washington Island, Wisconsin at a willow-gathering retreat. (You can read more about Joy’s willow-gatherine process in an earlier arttextstyle post.) She picked up the rock on the shores of Lake Superior noting that it was very different rock there than in Montana where she lives. “It was so black, sparkly, and geometric with a sharp point,” she says. “It occurred to me that rocks are just small landscapes. I started weaving around the rock during the retreat. Then, I let it sit for over a year; I just didn’t have the right color willow to work on it.” Eventually, she added more yellow. “I really like the color, like sunset in the clouds. The yellow changes colors slowly as it dries, losing some of its vibrancy, but blending better with the brown willow.”

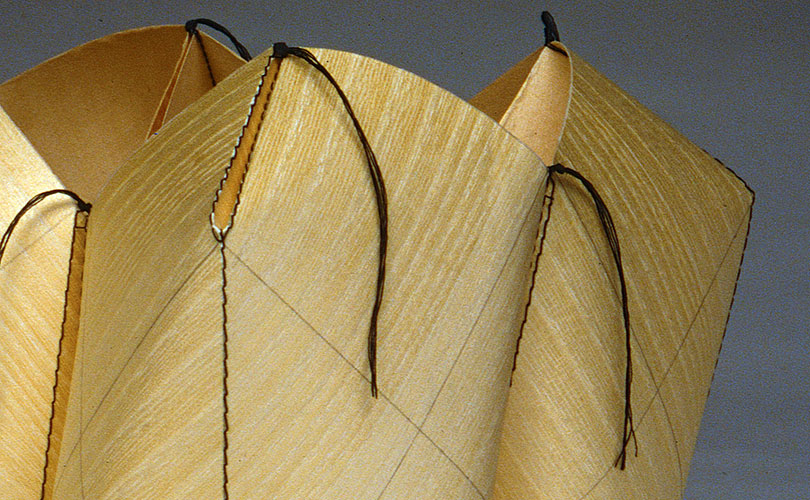

Caroline Bartlett explores the historical, social, and cultural associations of textiles, their significance in relation to touch and their ability to trigger memory, in her work. She Imprints, stitches, erases, and reworks cloth, folding and unfolding, and often integrating textiles with other media such as porcelain. Her new work, Juncture, she says, “suggests ‘a point of time, especially one made critical or important by a concurrence of circumstances’ while disjuncture suggests ‘a disconnection between two things. The language of textiles speaks of entanglements and connectivity, of continuity and severance, and pink might be considered as a field for nurture. Blocks of intersecting color are revealed through a manipulated surface and hold firm with concepts of control. Simultaneously, they become squeezed and threads displaced as notions of old certainties and understandings fall away. The whole becomes a metaphor for the personal or for the wider social, ecological, and political sphere.”

Thanks again to all the artists we work with who continually send us such marvelous work. Keep watching; we’re committed to showing and sharing more art online and in person.