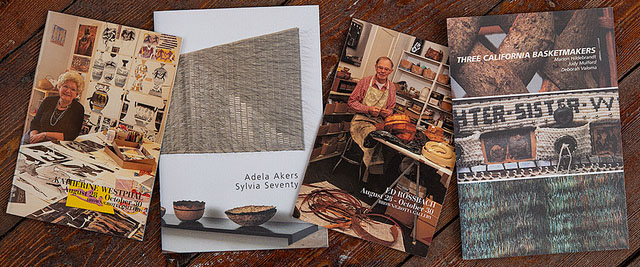

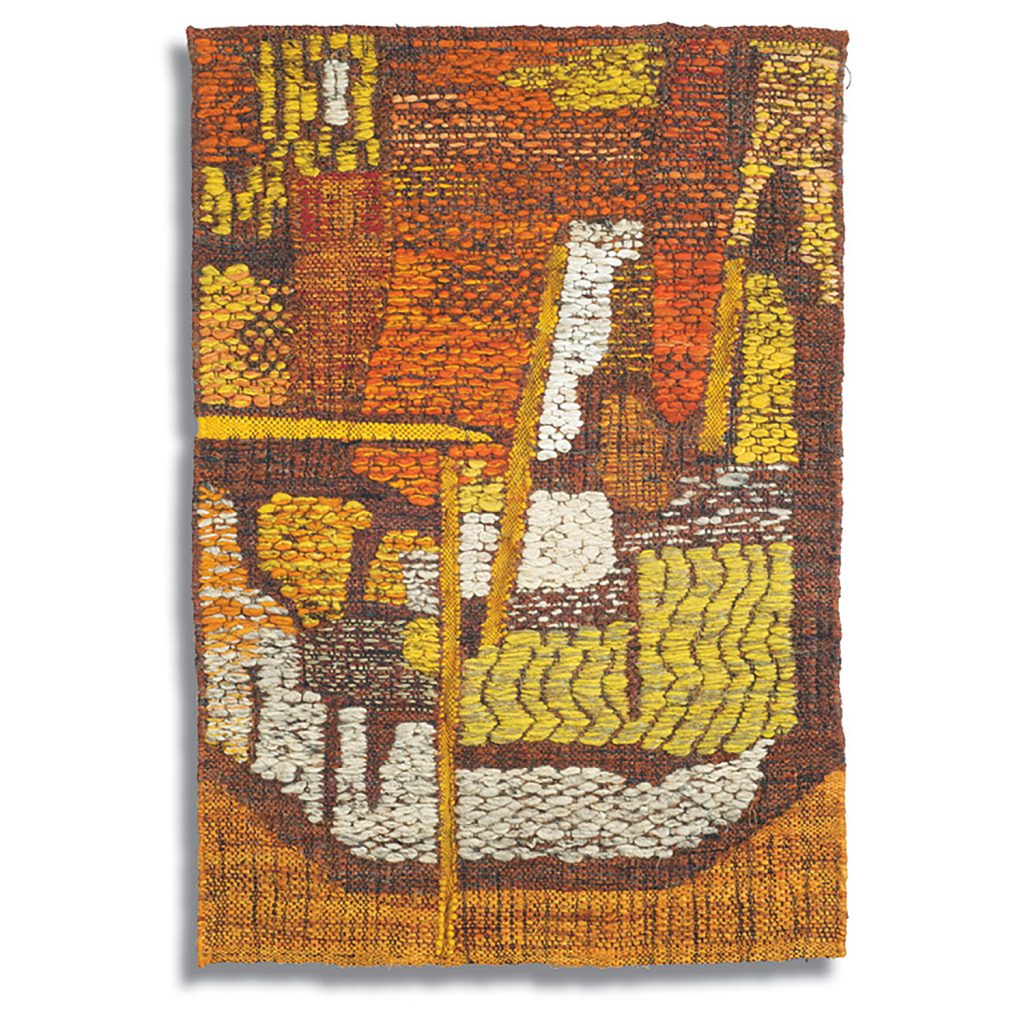

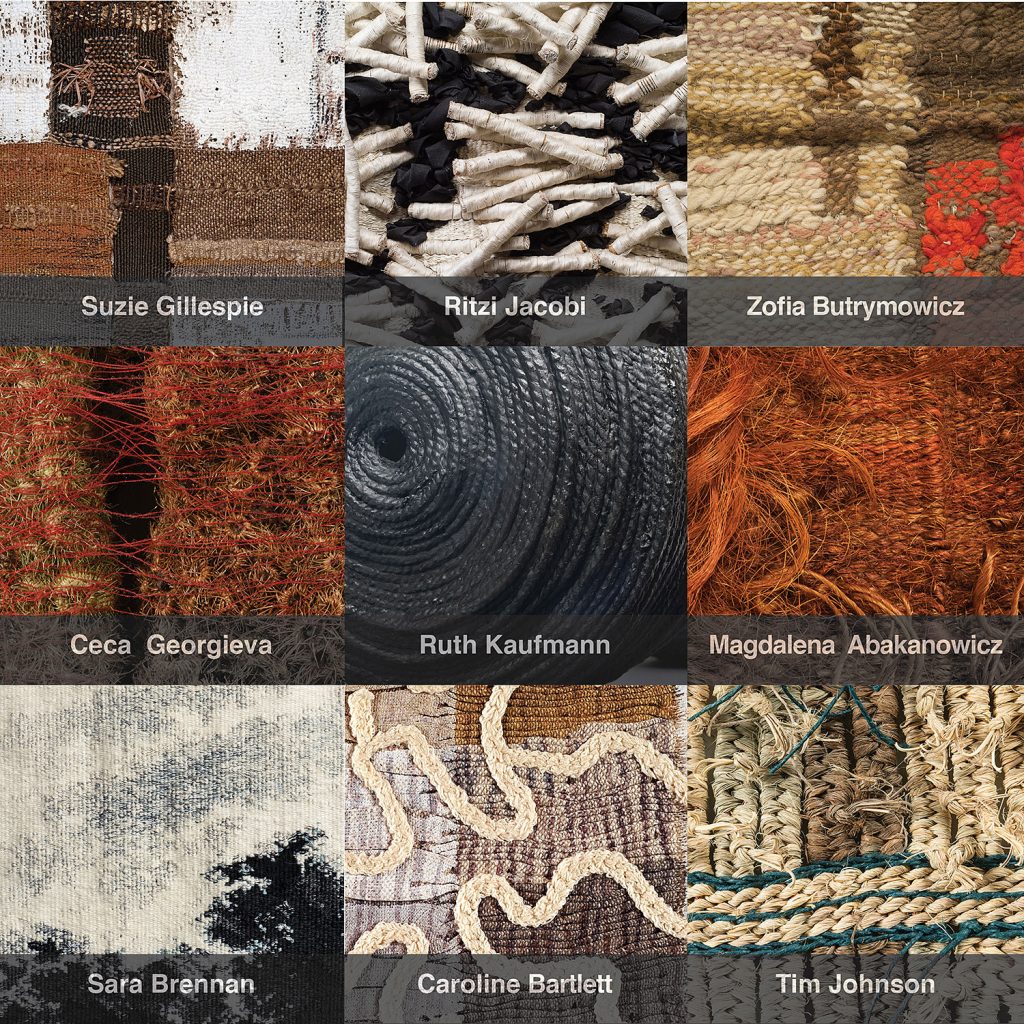

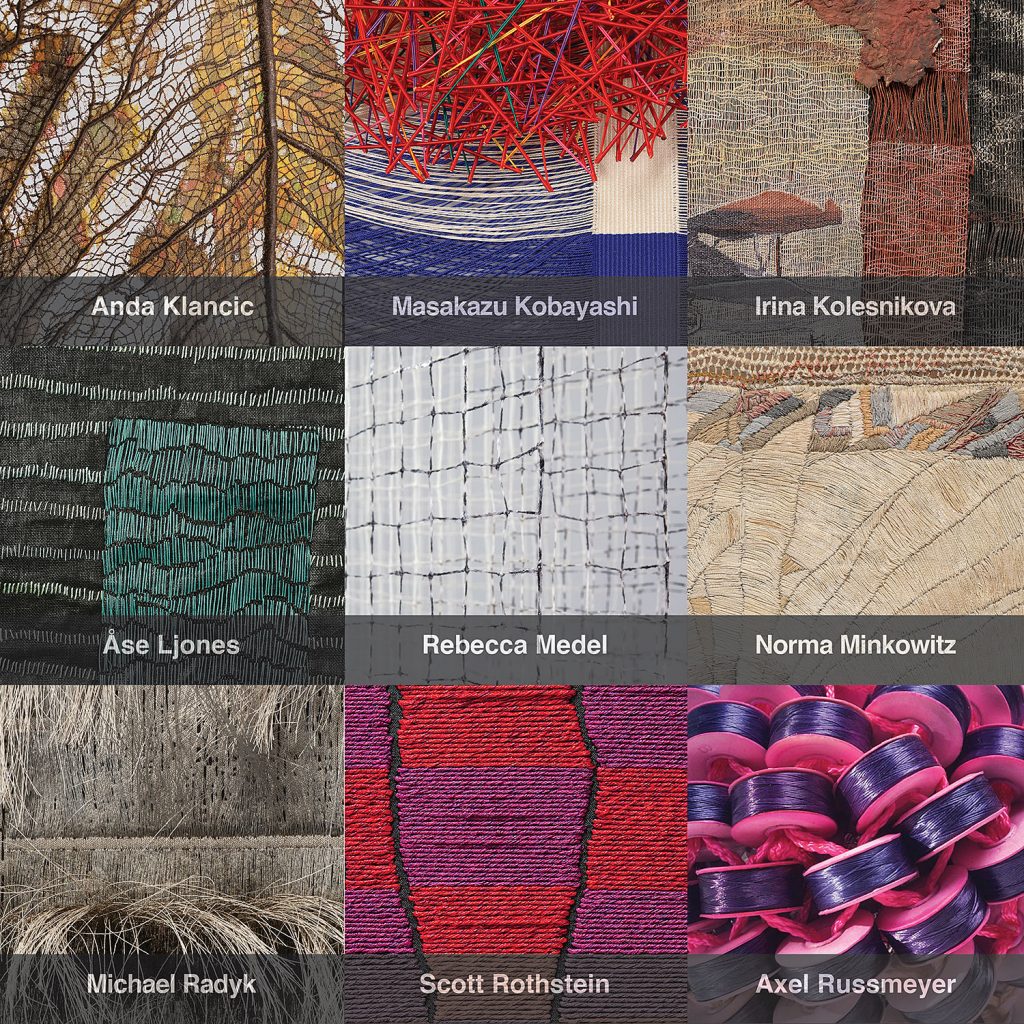

Rippling, roiling, teeming with life…Deep, dark, waiting to be explored…Water has long been a potent influence for the artists we exhibit, artists who explore its mystery and majesty in widely divergent ways. Cross Currents: Water/Art/Influence is an online exclusive exhibition on Artsy that features works reflecting rivers, oceans and life aquatic. It highlights three catalogs we have published, Of Two Minds: Artists Who Do More Than One of a Kind, vol. 38; Plunge: explorations from above and below, vol. 43 and Blue/Green: color/code/context, vol. 44 and several artists for whom water has been an inspiration. The multifaceted exhibition combines sculptures, tapestries, installation works, paintings and ceramics. Each work resides at the intersection of the maker’s fascination with a variety of nautical and natural themes and the artmaking process.

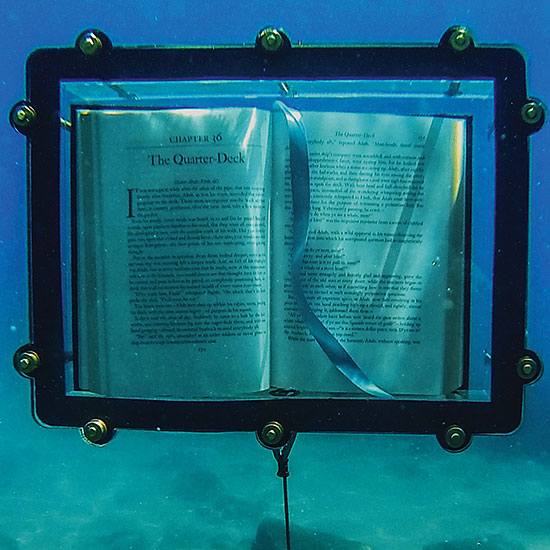

Judy Mulford’s meticulously detailed sculptures, inspired by her home at the beach in California, join Grethe Wittrock’s Arctica, a sculpture made from a repurposed sail from the Danish Navy. Debra Sachs‘ water studies evoke a sense of movement by distorting a static grid using the color blue as akin to a living thing, like the rivers and the oceans, shallow to deep, static to moving. Lawrence LaBianca creates experiences in which water is an integral part. In Skiff, an antique telephone receiver links viewers to sounds of a rushing river. Twenty-four Hours on the Roaring Fork River, Aspen, CO, is a print created by Drawing Boat, a vessel filled with river rocks that makes marks on paper when it is afloat. For What Lies Beneath/Moby Dick Book, LaBianca lowered an encased copy of Moby Dick into the water to capture an image. “I love the images that Melville created in Moby Dick, he says, “the idea of something greater below governed by forces deep within a person’s soul. What Lies Beneath/Moby Dick Book draws a continuum with the idea of something great below. It also is comical and slightly absurd.” Karyl Sisson works with found objects — clothespins, zippers, tapes — to create sea creature-like sculptures. In creating Haystack River Basket, Dorothy Gill Barnes was moved by the natural forms created of tree roots sculpted by rushing water.

In all, the work of 21 artists will be included in Cross Currents. Some are moved by water as a natural force, for others there is a more spiritual connection, still others are interested in how Man is impacting our oceans and rivers — in each case the results are thought provoking and intriguing. One-half of the works will appear on Artsy on June 8th, the reminder will be added on June 15th: https://www.artsy.net/show/browngrotta-arts-cross-currents-water-slash-art-slash-influence.

We Get Good Press

Maybe you’ve heard the buzz? In the past six months, both browngrotta arts and Tom’s book project, The Grotta House by Richard Meier: A Marriage of Architecture and Craft, which features many of the artists we work with, have gotten great coverage in the Connecticut publications, nationally and elsewhere in the world.

In December, the illustrious New York Times, profiled Sandy and Lou Grotta, their 300+ collection of Modern Craft which are beautifully featured/illustrated in The Grotta House book. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/31/arts/design/show-us-your-wall-grotta.html So did Art in America online.

https://www.artguide.pro/event/ book-release-the-grotta-home-by-richard-meier-a-marriage-of-architecture-and-craft/ Tom got a shoutout as the photographer in both articles as well. Next up was TLmag, True Living of Art and Design, a Brussels-based, international biannual print and online magazine dedicated to curating and capturing the collectible culture.

Also in February, the Grotta house and browngrotta arts were covered by Introspective, the online magazine produced by 1st Dibs, In the piece titled, “Tour a Richard Meier-Designed House that Celebrates American Craft,” author Osman Can Yerebakan, observes that the Grottas, are “[l]ed by intuition, they simply let an affinity for objects, and for the people who make them, guide their unerring eye.”https://www.1stdibs.com /introspective-magazine/richard-meier-grotta-house/?utm_term=feature2&utm_source=nl-introspective&utm_content=reengagement&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=2020_02_23&emailToken=2277332_1a3d078b2c480b774c0897f7484ece12b4545b9bb006358a40eba4b7215550ce

Japanese and Korean Contemporary Craft

in Artfix Daily

On March 1st, Artfix Daily covered our online exhibition in “browngrotta arts presents Transforming Tradition: Japanese and Korean Contemporary Craft.” http://www.artfixdaily.com /artwire/release/7876-browngrotta-arts-presents-transforming-tradition-japanese-and-kor. An article by Rhonda, “Active Collecting: Acquiring Experiences as Well as Art,” appeared in the Spring issue of Surface Design Journal,

as Well as Art in Surface Design Journal

describing the interactions between Sandy and Lou Grotta and the artists they collect. The couple have met many of those whose work they have collected or commissioned and have developed deep friendships with others, including furniture makers Joyce and Edgar Anderson and Thomas Hucker, jewelers Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins, ceramist Toshiko Takaezu and weaver Mariette Rousseau-Vermette.

The Spring also saw a light-hearted story in the March/April issue of Wilton Magazine, on Rhonda and Tom, “Art of Love, Love of Art,” by Karen Sackowitz, noting that our creative synergy– for better or worse — has spanned decades (3 decades and 7 years to be precise). Other local publications have championed us as well — The Ridgefield Press, Wilton Bulletin and Connecticut Magazine have talked up our taking art online, nothing that, “Social distancing doesn’t mean people have to distance themselves from the arts” as area arts institutions like bga have taken to providing people with digital experiences on their websites and social media platforms to ensure people are still able to engage with art.

with a Rotating Cast

of Craft Masterpieces

by Casey Lesser: Artsy Editorial

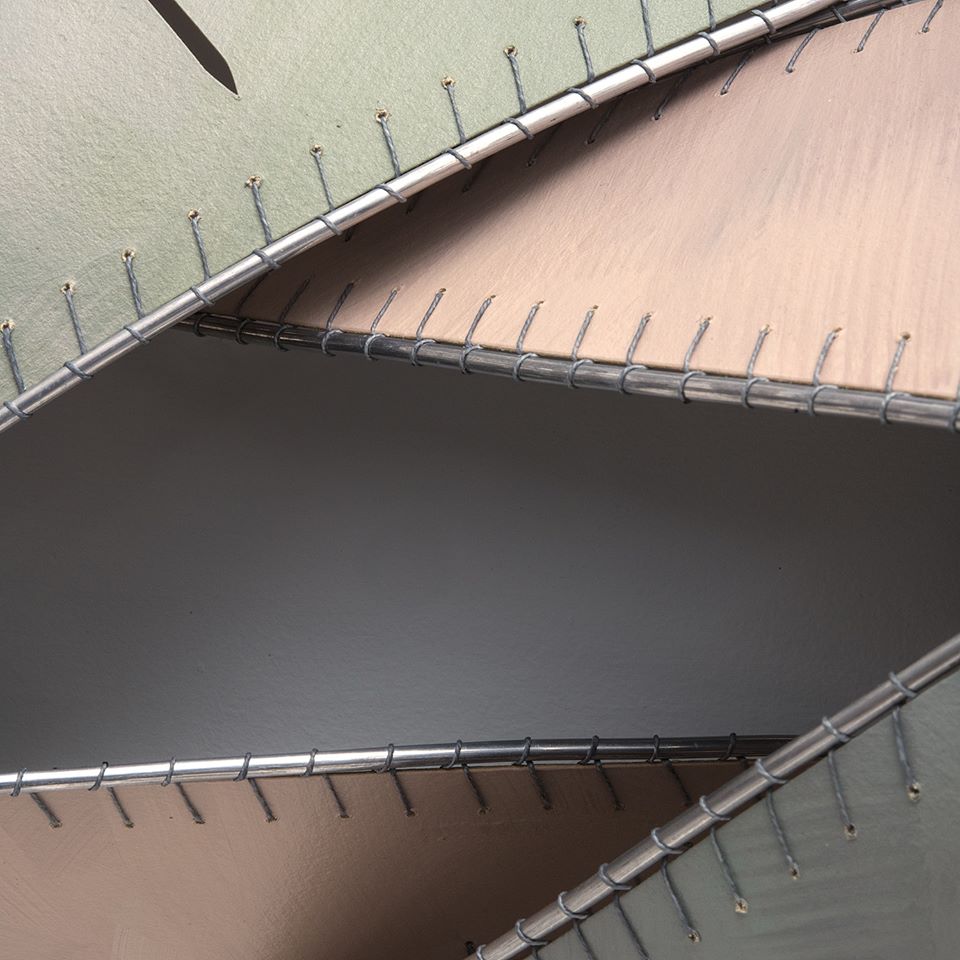

Artsy, covered the Grottas and their home in April, in “This Collecting Couple Lives with a Rotating Cast of Craft Masterpieces,” by Casey Lesser https://www.artsy.net /article/artsy-editorial-collecting-couple-lives-rotating-cast-craft-masterpieces. Tom got a shout out, too. The author shared Lou’s collecting advice to “do your homework” as he recalled being told that “you have to see 50 works by an artist before you can start to understand what’s good.” Thanks to the internet, that’s much easier today than it was when he and Sandy started out. “Don’t fall in love with the latest stuff,” the author quotes Grotta. “Decide who you like and what you like.”

April also saw the Grotta house and book featured in Dwell online https://www.dwell.com /home/the-grotta-house-0257ab73 and in Archello https://archello.com/project/the-grotta-house. In progress (fingers crossed), a piece on The Grotta House by Richard Meier, a Marriage of Architecture and Craft in INTERIOR+DESIGN, a Russian publication.

We hope to get press coverage for our upcoming events:

Online in June: Cross Currents – Arts Influenced by Rivers and the Sea, Vols. 38, 35

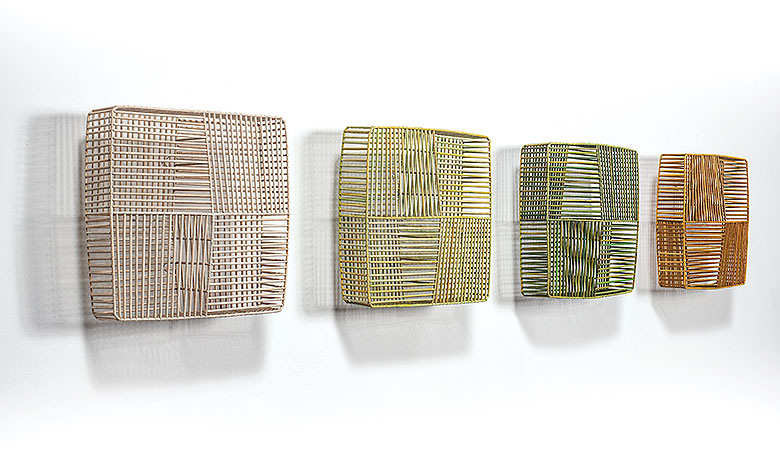

Online in July: Fan Favorites — Sekimachi, Sekijima, Laky and Merkel-Hess, Vols. 24, 19, 2, 3, 8, 5, 15, 16, 19

Online in August: Cataloging the Canon – Tawney, Stein, Cook, Hicks and So, Vols. 13, 28, Monographs: 1-3; Focus: 1

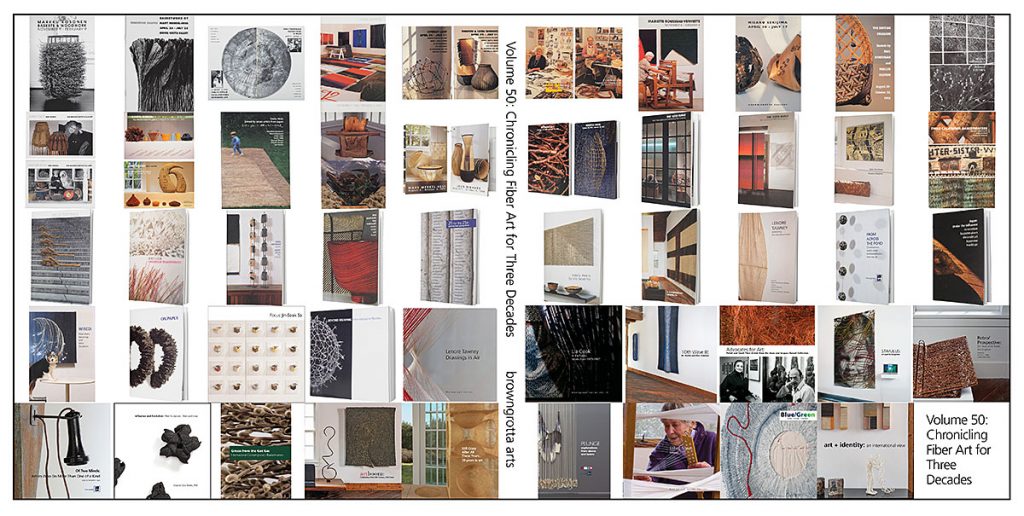

Live in September: Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber for Three Decades. Now rescheduled for September 12 -22. Details on how we will mix art viewing and safe practice to come.

Hope you’ll join us for all or some of these.

Stay Safe, Stay Distanced, Stay Inspired!!