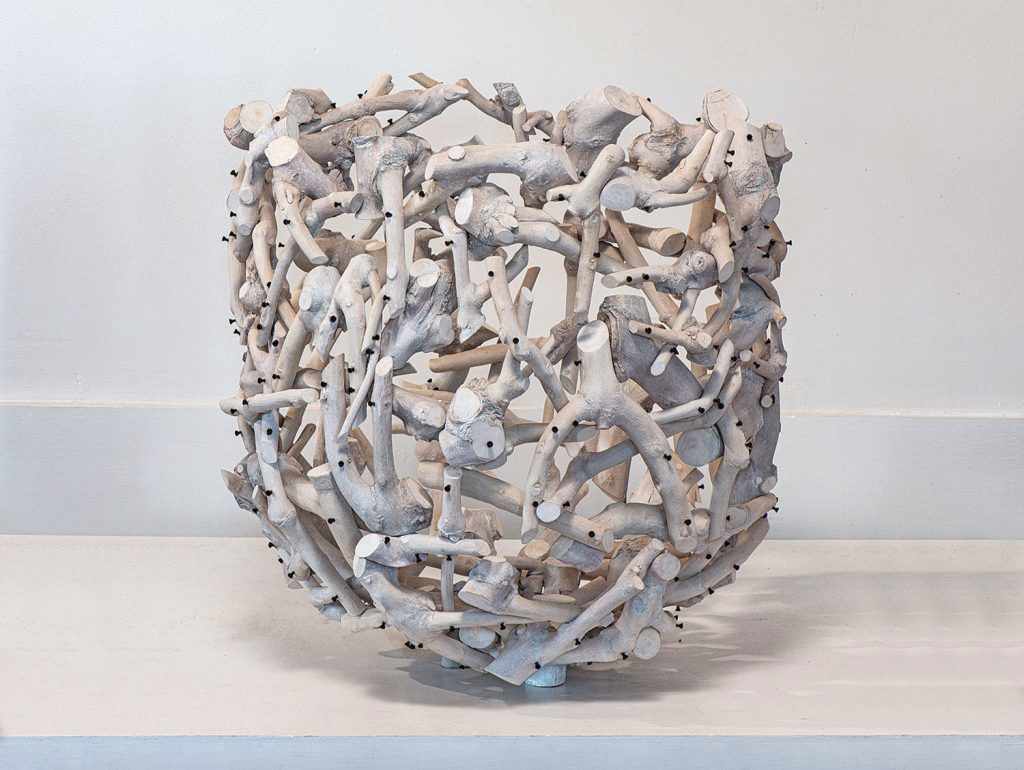

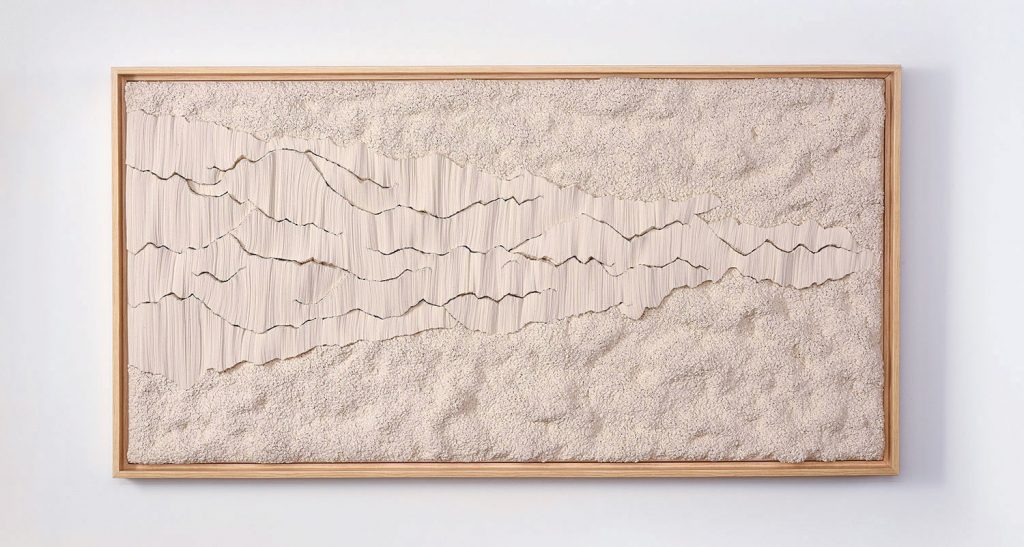

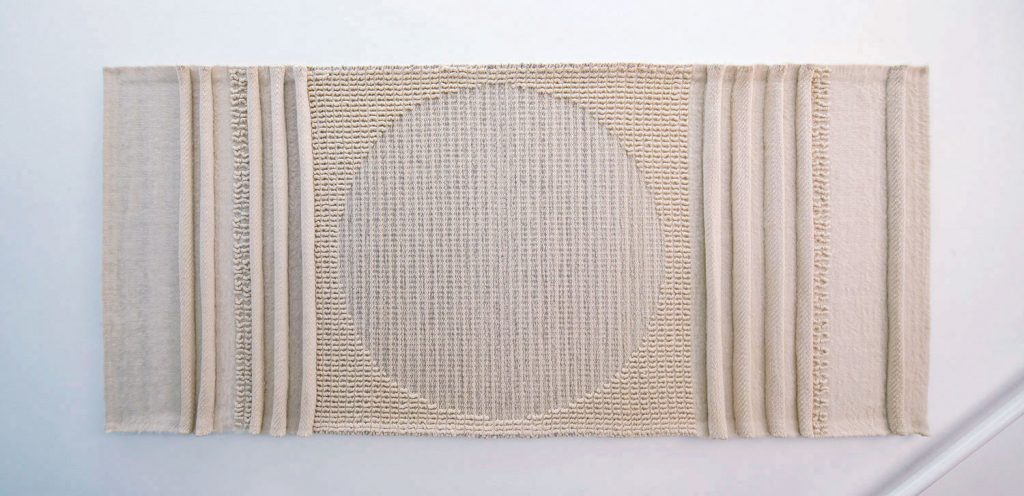

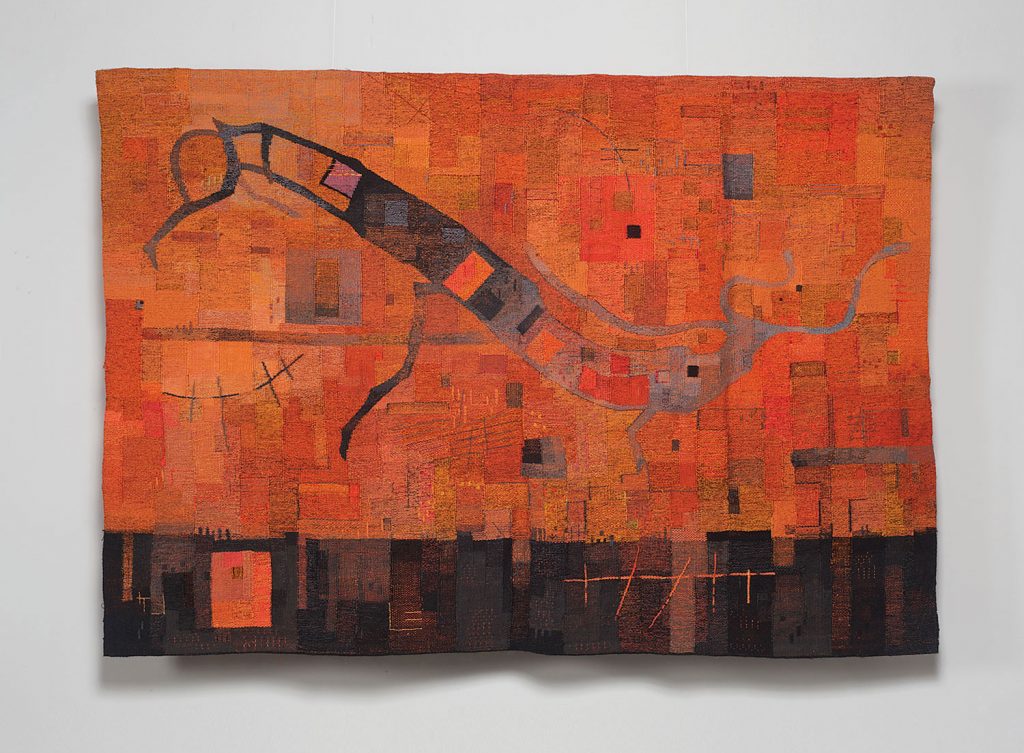

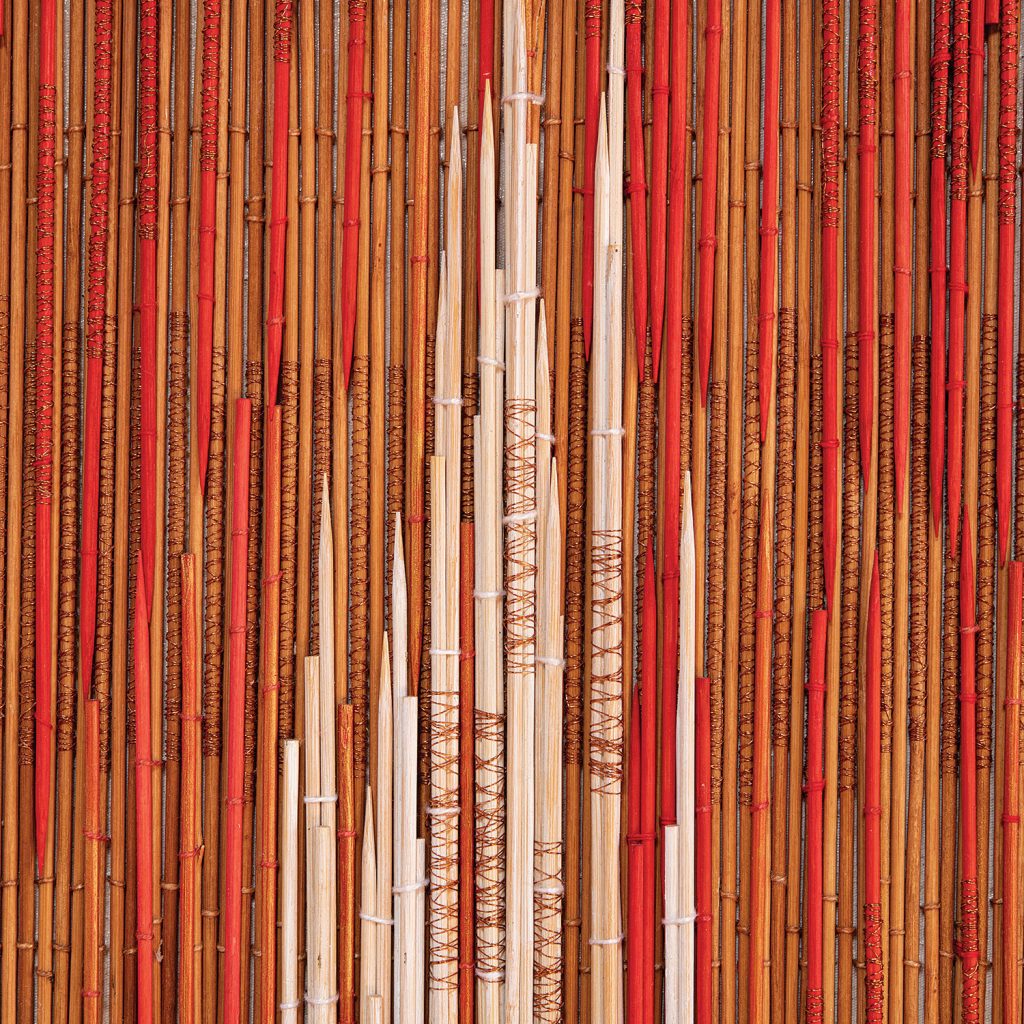

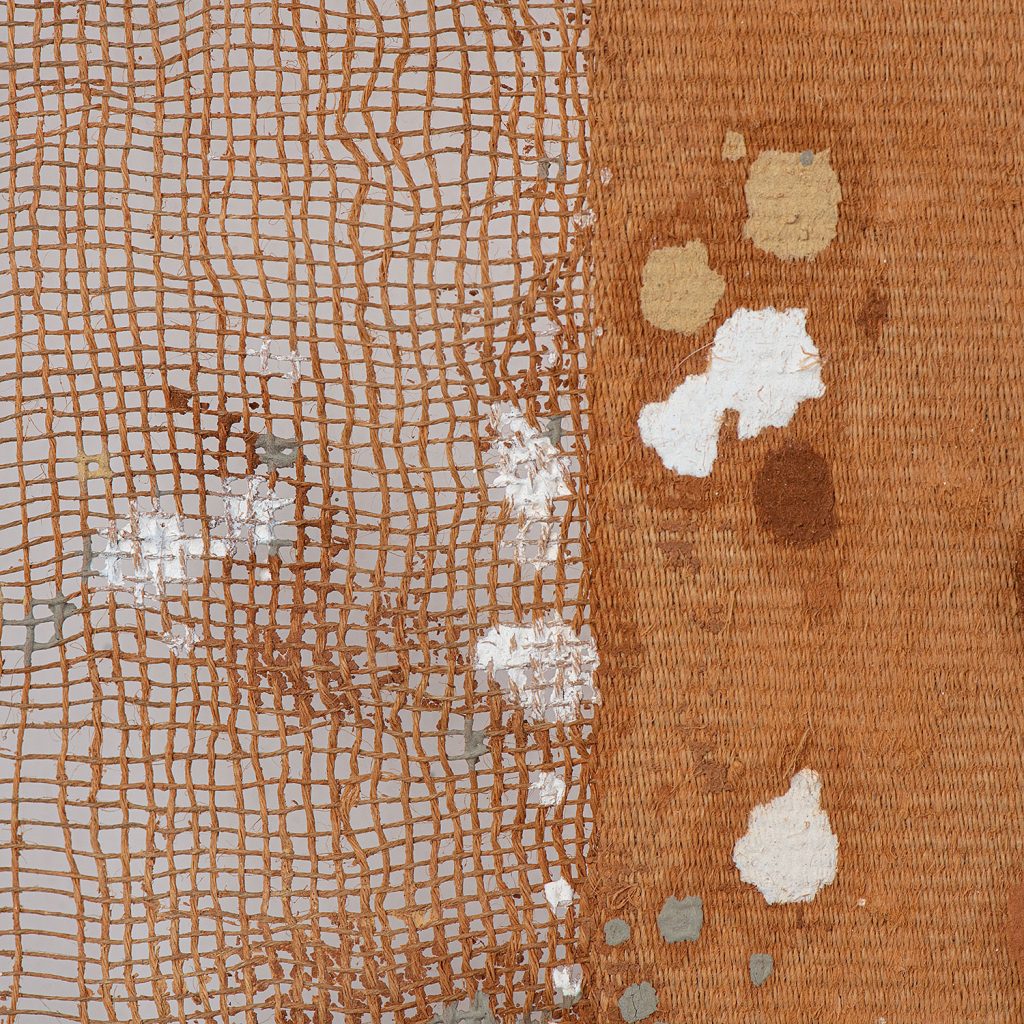

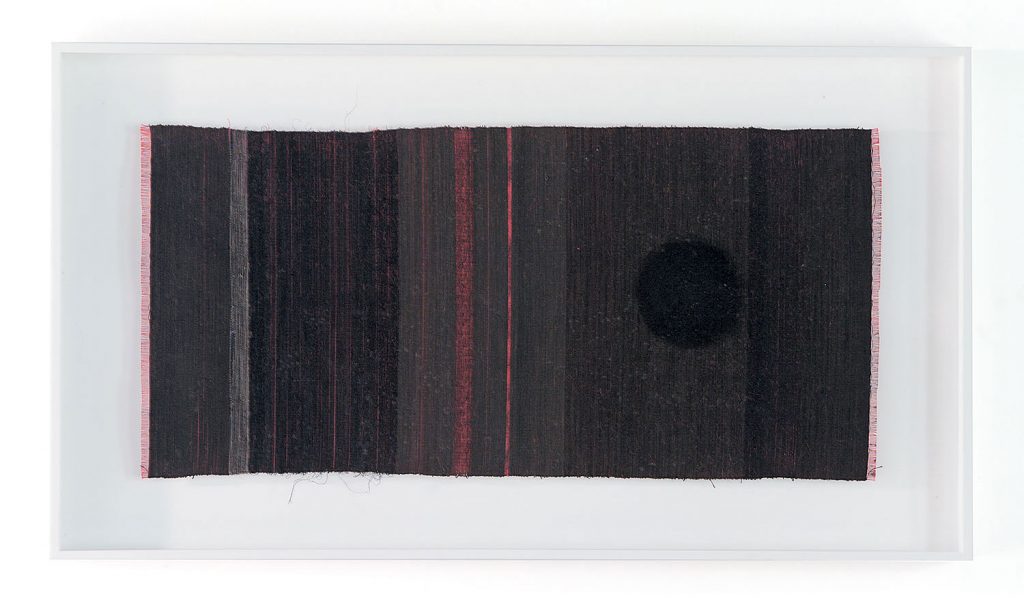

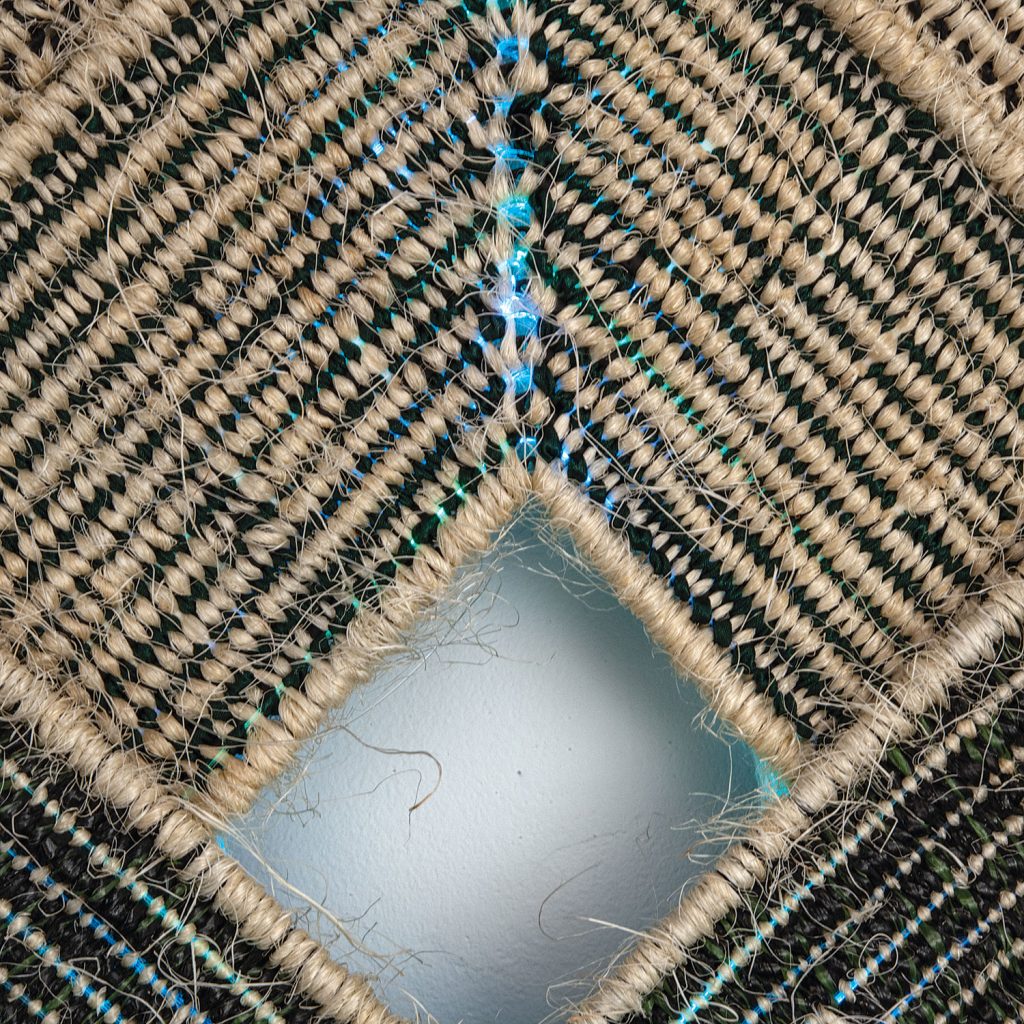

Japanese artist, Naoko Serino, our focus this week, works in jute, a remarkably adaptable material that provokes references to other biological structures. Jute’s golden sheen and sinuous strands “yield a most spectacular softness and luminosity,” notes author Moon Lee (http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/naoko-serino-spins-vegetable-fiber-into-golden-sculptures). In Serino’s work, “the natural fibers are spun densely or pulled thin, making for infinite gradations of densities. Irregular shapes in varying degrees of transparency provoke an effect that is strongly biological. Spheres, tubes, tubes contained within spheres, spheres contained within cubes, and rows of coiled strands evoke thoughts of phospholipid bilayers of cell membranes, veins, sea sponges, and so forth.”

Serino creates her sculptures by first covering molds with jute fibers, which she removes when they have dried, creating a final work combining individual fiber elements. Some of the works that Serino creates are small individual pieces, while others are installations that are large enough to fill an entire room. Despite the fragile appearance of the jute fibers, the works have an imposing presence.

“I moved to a seaside town 30 years ago. I felt the light and wind there and my feelings were stirred by my proximity to Nature,” Serino says. “I began to see with new eyes and I discovered a material, jute. I think the discovery was inevitable. In and through my hands, a dignified hemp produces a shape that contains both light and air. I am grateful that I came across this material. It is a joy for me to express things with jute that stir deep emotions in me. I see myself continuing to express my feelings in this form.”

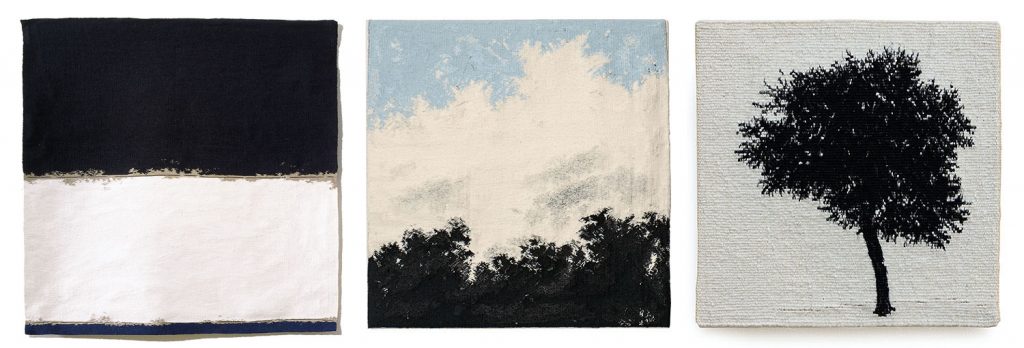

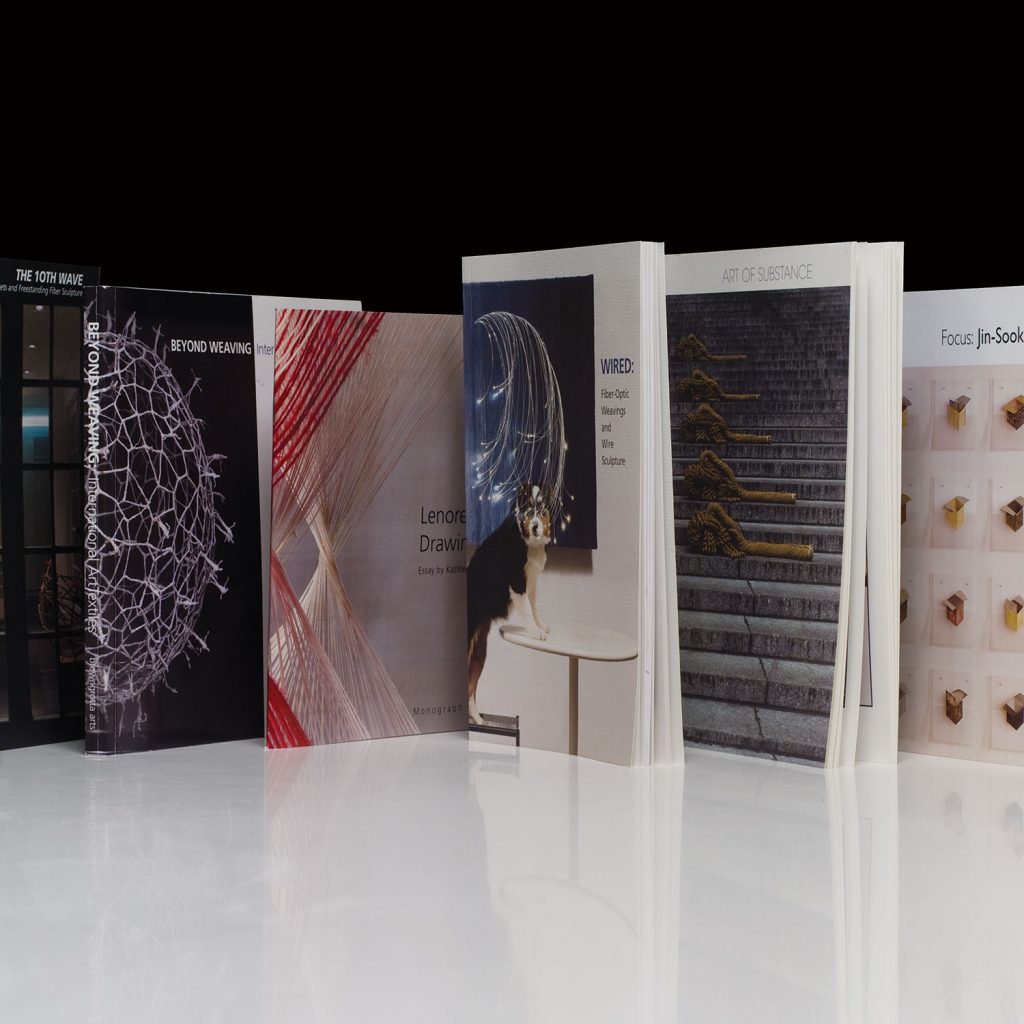

Serino’s work was included in the Fiber Futures: Japan’s Textile Pioneers exhibition which traveled from Japan to New York, Milan, Copenhagen and other venues. She was awarded the Silver Prize in the 10th Kajima Sculpture Competition and the Encouragement Award in the 16th Kajima Sculpture Award in 2020. She was a awarded the first prize in the Collection Arte & Arte alla Torre delle Arti di Bellagio, Como, Italy in 2014, the Silver Prize in the 10th Kajima Sculpture Competition and the Encouragement Award in the 16th Kajima Sculpture Award in 2020.

Serino is one of the artists whose work is included in browngrotta arts’ next Art in the Barn exhibition, Adaptation: Artists Respond to Change (May 8th – May 16th) http://www.browngrotta.com/Pages/calendar.php. Her work for the exhibition, Generating-Mutsuki, came out of her desire to create a work along the lines of the large-scale sculpture she created for Kajima Sculpture competition in a smaller size.