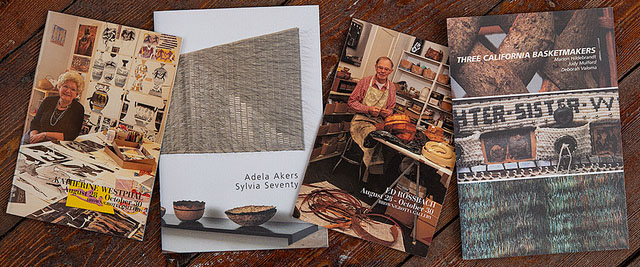

Ed Rossbach | Katherine Westphal | Marion Hildebrandt | Judy Mulford | Deborah Valoma | Adela Akers | Sylvia Seventy

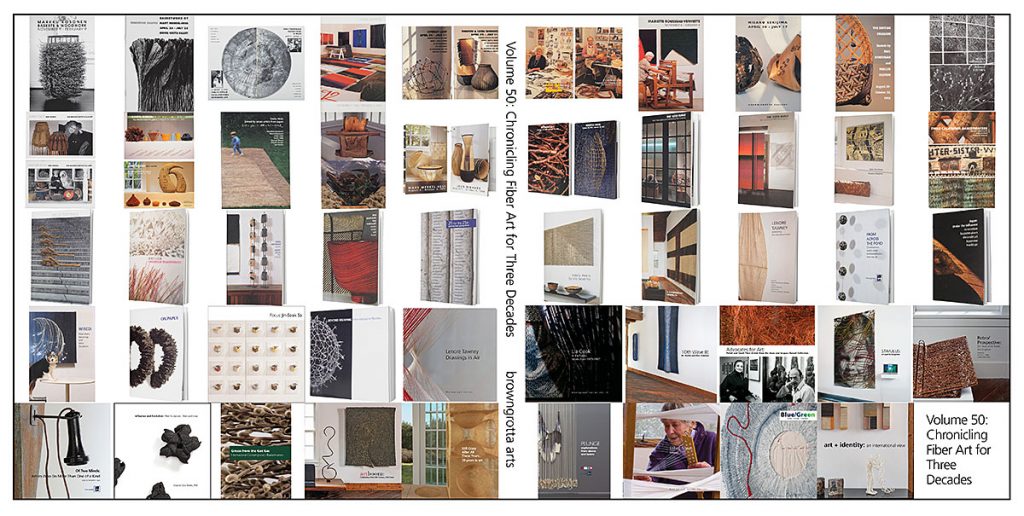

California has played a seminal role in both the history of the Contemporary Fiber Arts Movement and artists from California have played an equally significant role in browngrotta arts’ exhibition archive. You’ll find California artists represented in nearly all our group catalogs: Lawrence LaBianca in Stimulus: Art and its Inception (vol. 36); Carol Shaw-Sutton in 25 for the 25th (vol. 25); Nancy Moore Bess in 10th Wave I (vol. 17) and 10th Wave II (vol. 18); Karyl Sisson in Karyl Sisson and Jane Sauer (vol. 12) and Ferne Jacobs in Blue/Green: color/code/context (vol. 44).

California Dreamin’, an online exhibition on Artsy from May 11 to June 5th, features seven artists: Ed Rossbach, Katherine Westphal, Marion Hildebrandt, Judy Mulford, Deborah Valoma, Adela Akers and Sylvia Seventy. The exhibition borrows from three browngrotta catalogs (vols. 6, 20, 26) and highlights decades worth of art.

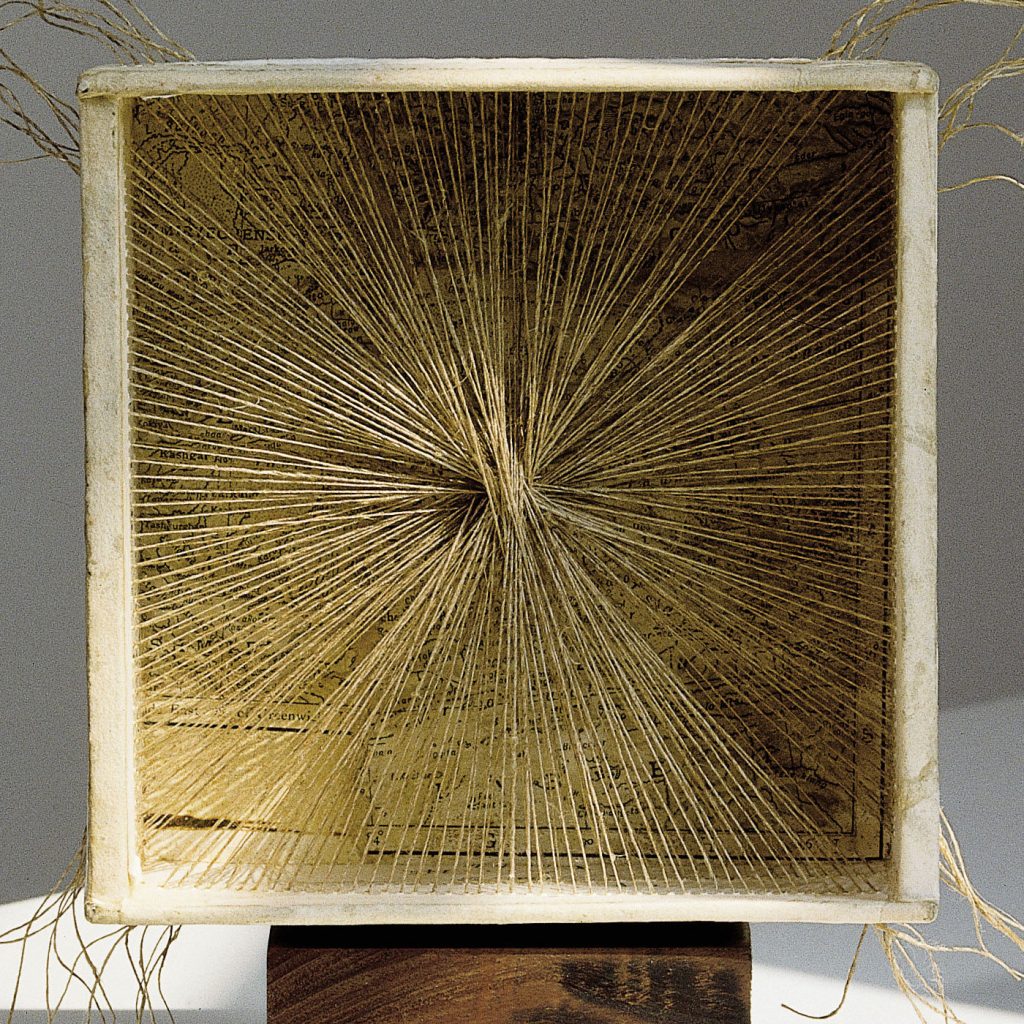

Best-known of the group, Ed Rossbach, completed his graduate studies at Cranbrook in 1946. He, along with Marianne Strengell worked within the narrow parameters of Euro-Bauhaus-Scandinavian weaving traditions for industry. “In reaction to this tight definition of textiles,” Jo Ann C. Stabb wrote in Retro/Prospective: 25+ Years of Art Textiles and Sculpture (vol. 37), “Rossbach became fascinated by indigenous textile processes and the use of found materials as he studied artifacts in the anthropology collection at University of California, Berkeley, as a faculty member from 1950 to 1979. Noted for creating three-dimensional, structural forms from unexpected, humble materials including plastic, reeds, newspaper, stapled cardboard, twigs, Rossbach inspired a renaissance in basketry and vessel forms and influenced other artists, including his students Gyöngy Laky and Lia Cook.”

Katherine Westphal, who was married to Rossbach, generated experiments of her own. In the late 60s she was among the first artists to use photocopy machines to make images for art. In the 1970s, in addition to drawings to baskets, she began creating wearable art, which, according to Glenn Adamson, former director of the Museum of Arts and Design. was a genre she essentially invented. She wanted it said of the graments she created: “there wasn’t another one like it in the world, and most people probably wouldn’t be caught dead in it.” Few were worn, most were hung on the wall like paintings. Her work displayed wide-ranging, autobiographical themes, arising from her travels: Native American art from trips through the Southwest, cracked Greek pots viewed on a trip to the Met, portraits of geishas after visiting Japan. “I want to become a link in that long chain of human activity, the patterning on any surface available,” she said.

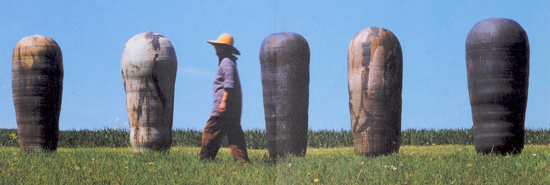

Also in the 70s, Sylvia Seventy, inspired in part by her studies of the art of the Pomo Indians, was exploring her own innovative techniques in paper making. In 1982, The New York Times said of her works, “The vessel forms of Sylvia Seventy, all produced over molds, are rich, earthy bowl shapes, with embedded bamboo, cotton cord and sisal. From a distance they appear to be hard, perhaps stoneware; on closer inspection, they are fragile works.” Her vessels feature an accretion of items: compositions of beads, feathers, fishhooks, googly eyes, hand prints, and buttons, creating what Charles Tally called “emotionally poignant landscapes within the interior of the vessel[s].” (Artweek, November 29, 1990).

Deborah Valoma, author, art historian and creator of both textile and sculpture, heads the Textiles Program at the California College of Arts and Crafts (Oakland). Valoma credits numerous influencers for her work: “I first learned to knit in Jerusalem from a Polish refugee of the Holocaust. I learned to stitch lace from my grandmother, descendant of Armenian survivors of the Turkish massacres. I learned to twine basketry from one of the few living masters of Native American basketweaving in California. These dedicated women tenaciously pass the threads of survival forward. When their memory fails, my hands remember. My hands trace the breathless pause when I teeter on the sharp edge of sorrow and beauty.” Using hand-construction techniques and cutting-edge digital weaving technology, her work hugs the edges of traditional practice. She upholds traditional customs and at the same time, unravels long-held stereotypes. Valoma believes that students must locate themselves within historical lineages in order to understand the historical terrain they walk — and sometimes trip — through daily.

Marion Hildebrandt lived and worked in Napa Valley, gathering most of the plant material used in her baskets from the region until her death in 2011. “My works are a coming together of my life experiences,” Hildebrandt said. “My basketmaking reflects a longtime interest and study of native California flora and fauna.” Hildebrandt employed the same materials that Native Americans used when they inhabited the area. “It is still possible to find plants here that were used by basketmakers 4000 years ago,” she noted. Although she never attempted to replicate their baskets, she shared a similar appreciation for the natural materials that surrounded her. “Ever so subtly, plants cycle from winter to summer,” she observed. “Each day, week, month brings changes that effect the materials that I collect and use for my baskets.”

Further down the California coast, Judy Mulford continues to create her narrative sculptures and baskets of gourds. Mulford studied Micronesian fiber arts and in the 70s was one of a group of women who worked on Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party. She says each piece she creates “becomes a container of conscious and unconscious thoughts and feelings: a nest, a womb, a secret, surprise or a giggle. And always, a feeling of being in touch with my female ancestral beginnings.” Her sculptures integrate photo images, drawings, script, buttons and small figures. Mulford explains: “The gourds are surrounded by knotless netting – an ancient looping technique – symbolic because it is also a buttonhole stitch historically rooted in the home.”

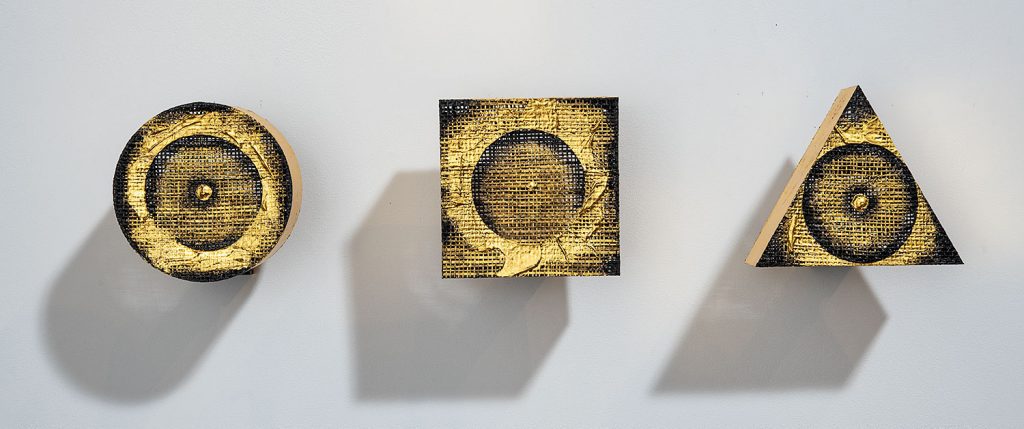

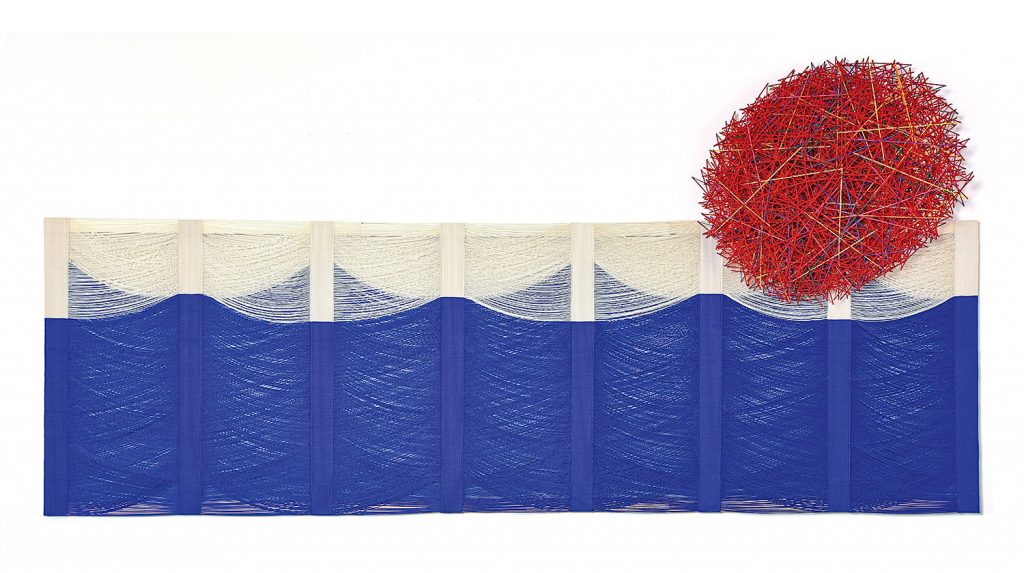

In the 1970s, Adela Akers on the East Coast teaching at Temple University, but she has been creating art as a resident of Califonia for the last 25 years. Drawing inspiration from African and South American textiles, Akers creates woven compositions of simple geometric shapes, bands, zigzags and checks. Many of her works incorporate metal strips — meticulously measured and cut from recycled California wine bottle caps. Her techniques and materials produce images that change under different lighting conditions. Akers also frequently incorporates horsehair into her weavings, adding texture and dimensionality. Over time, Akers’ work has evolved in scale, material and construction. Yet, several themes reoccur, notably the use of line which, in conjunction with light, brings forth the transformative quality that uniquely characterizes her work.

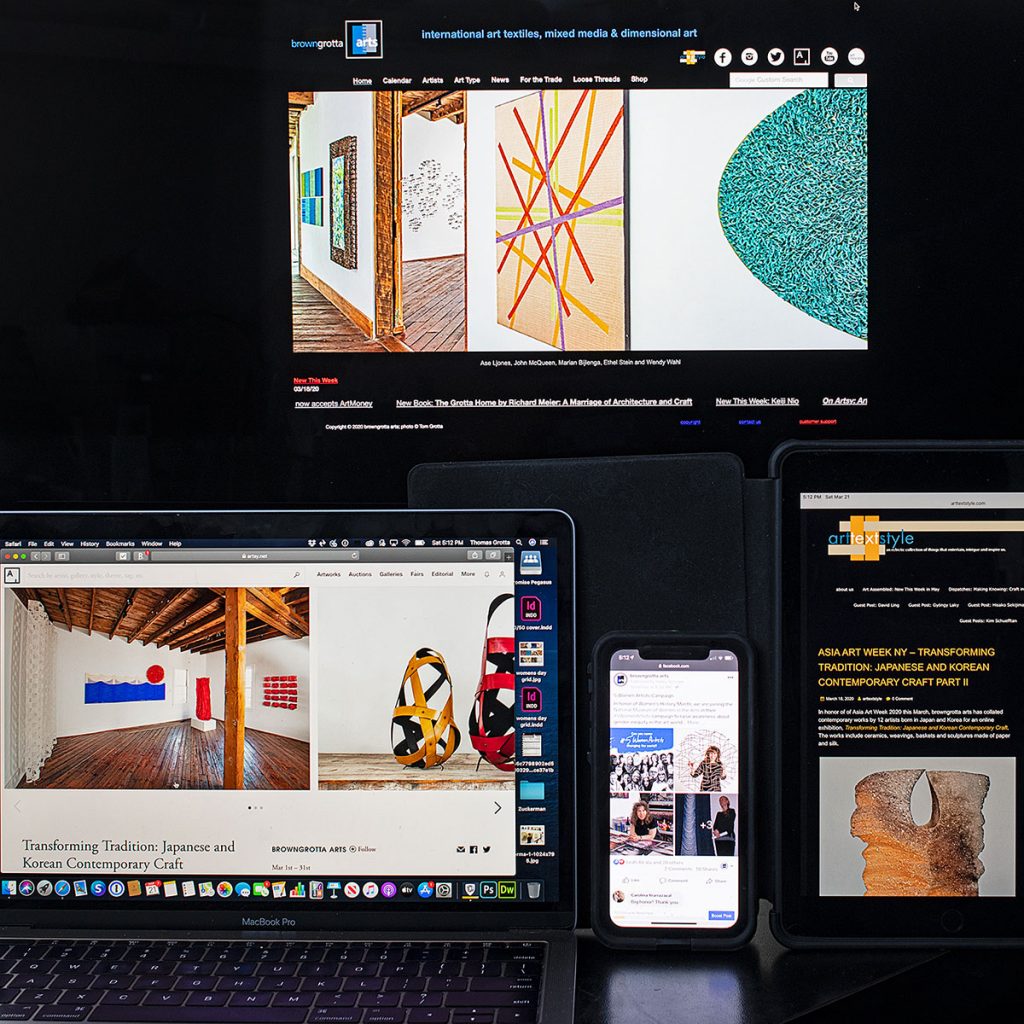

From May 11th to June 7th, view an assortment of works by these artists at California Dreamin’ on Artsy

Art & Identity: A Sense of Place

In our 2019 Art in the Barn exhibition, we asked artists to address the theme of identity. In doing so, several of the participants in Art + Identity: an international view, wrote eloquently about places that have informed their work. For Mary Merkel-Hess, that place is the plains of Iowa, which viewers can feel when viewing her windblown, bladed shapes. A recent work made a vivid red orange was an homage to noted author, Willa Cather’s plains’ description, “the bush that burned with fire and was not consumed,” a view that Merkel-Hess says she has seen.

The late Micheline Beauchemin traveled extensively from her native Montreal. Europe, Asia, the Middle East, all influenced her work but depictions of the St. Lawrence River were a constant thread throughout her career. The river, “has always fascinated me,” she admitted, calling it, “a source of constant wonder” (Micheline Beauchemin, les éditions de passage, 2009). “Under a lemon yellow sky, this river, leaded at certain times, is inhabited in winter, with ice wings without shadows, fragile and stubborn, on which a thousand glittering lights change their colors in an apparent immobility.” To replicate these effects, she incorporated unexpected materials like glass, aluminum and acrylic blocks that glitter and reflect light and metallic threads to translate light of frost and ice.

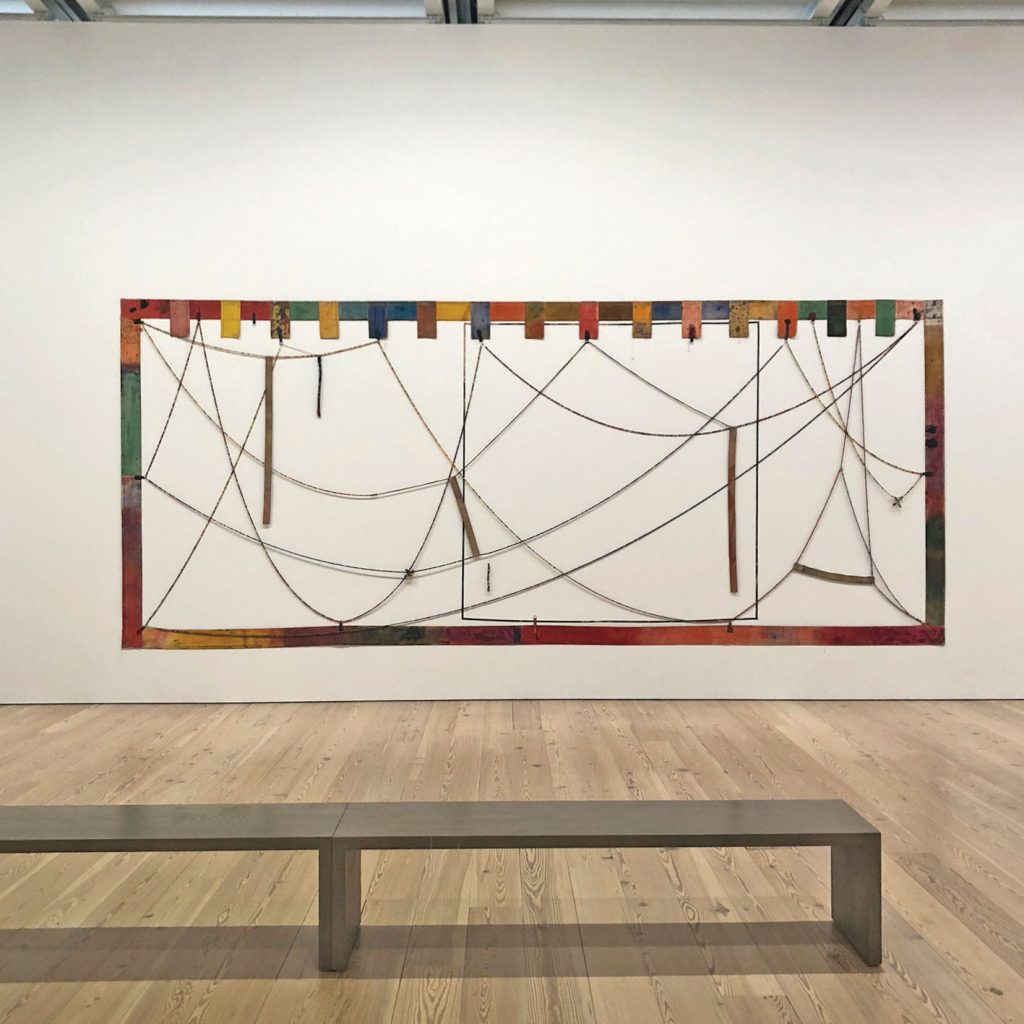

Mérida, Venezuela, the place they live, and can always come back to, has been a primary influence on Eduardo Portillo’s and Maria Davila’s way of thinking, life and work. Its geography and people have given them a strong sense of place. Mérida is deep in the Andes Mountains, and the artists have been exploring this countryside for years. Centuries-old switchback trails or “chains” that historically helped to divide farms and provide a mountain path for farm animals have recently provided inspiration and the theme for a body of work, entitled Within the Mountains. Nebula, the first work from this group of textiles, is owned by the Cooper Hewitt Museum.

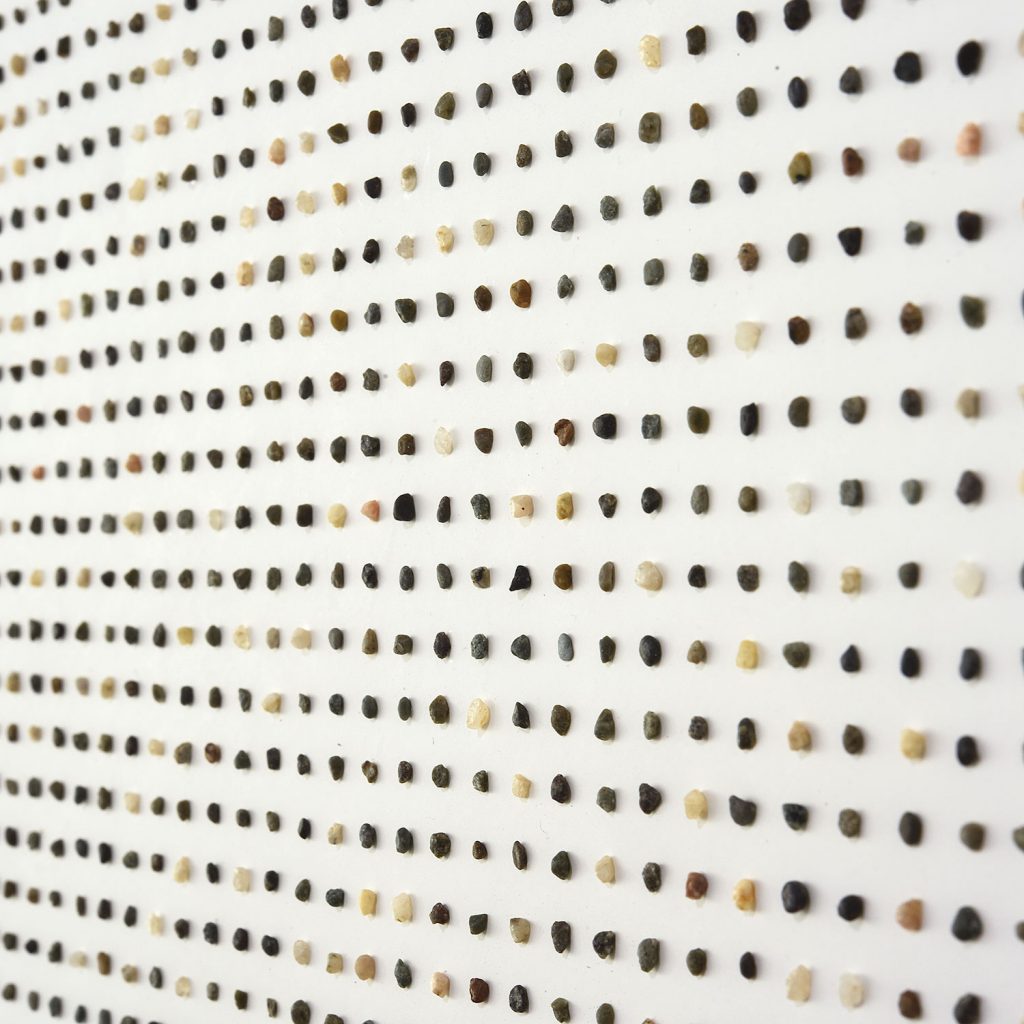

Birgit Birkkjaer’s Ode for the Ocean is composed of many small woven boxes with items from the sea — stones, shells, fossils and so on — on their lids. ” It started as a diary-project when we moved to the sea some years ago,” she explains. “We moved from an area with woods, and as I have always used materials from the place where I live and where I travel, it was obvious I needed now to draw sea-related elements into my art work.”

“I am born and raised in the Northeast,” says Polly Barton, “trained to weave in Japan, and have lived most of my life in the American Southwest. These disparate places find connection in the woven fabric that is my art, the internal reflections of landscape.” In works like Continuum i, ii, iii, Barton uses woven ikat as her “paintbrush,” to study native Southwestern sandstone. Nature’s shifting elements etched into the stone’s layered fascia reveal the bands of time. “Likewise, in threads dyed and woven, my essence is set in stone.”

For Paul Furneaux, geographic influences are varied, including time spent in Mexico, at Norwegian fjords and then, Japan, where he studied Japanese woodblock, Mokuhanga “After a workshop in Tokyo,” he writes, “I found myself in a beautful hidden-away park that I had found when I first studied there, soft cherry blossom interspersed with brutal modern architecture. When I returned to Scotland, I had forms made for me in tulip wood that I sealed and painted white. I spaced them on the wall, trying to recapture the moment. The forms say something about the architecture of those buildings but also imbue the soft sensual beauty of the trees, the park, the blossom, the soft evening light touching the sides of the harsh glass and concrete blocks.”