From City Tree Trimmings to Industrial Harvest, Artist Gyöngy Laky’s Textile Architecture Addresses Contemporary Environmental Issues

Kristina Ratliff and Ryan Urcia

While many artists work conceptually to inspire awareness and address issues of climate change, artists of Fiber Art and Modern Craft have a unique and inherently harmonious relationship with the environment, from their intimate use of natural materials to the fundamentally “slow art” process of hand craftsmanship.

In terms of the materials they use, they most often come from the earth, from private garden cultivation and harvesting to regional sourcing of plant life – such as bamboo, willow and cedar, and their earthy “scraps” such as branches, grasses, bark and twigs – impress an intrinsic awareness of the origin of things. This, coupled with the preservation of age-old techniques such as weaving, knotting, tying and bundling, earn these creatives rightful acclaim as stewards at the interconnection of art and nature.

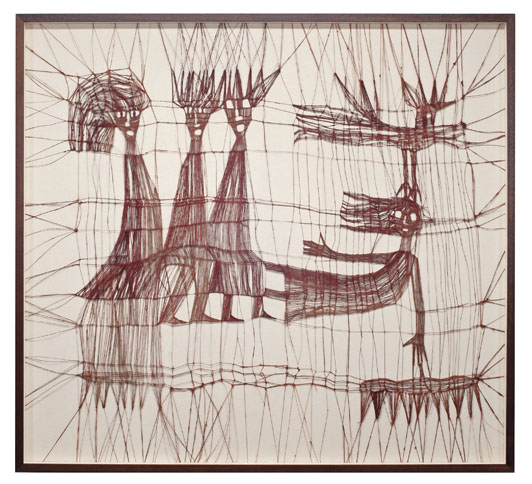

San Francisco-based artist Gyöngy Laky (most people call her Ginge, with a soft “g”) is known for her sculptural vessels, typographical wall sculptures, and site-specific outdoor works composed of materials harvested from nature — such as wood gleaned from orchard pruning, park and garden trimmings, street trees and forests of California — and discarded objects she considers “industrial harvest” such as recycled materials and post-consumer bits from surplus such as screws, nails, telephone wire.

“These annually renewable linear elements are regarded as discards,” Laky notes. “In my studio practice, however, they are employed as excellent and hardy materials.”

Born in Hungary in 1944, the physical and emotional effects of war impacted Laky from a very young age and her works often have underlying themes of opposition to war and militarism as well as climate change and the environment, gender equality. Her family emigrated to the US in 1949, resettling in Ohio, Oklahoma and eventually, California.

“After escaping the ravages of war as refugees,” she remembers, Nature’s embrace slowly healed my family,”

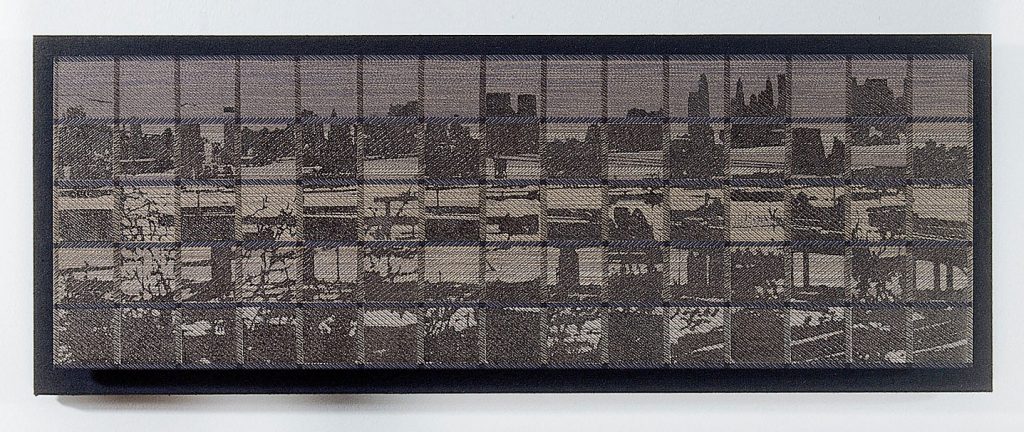

As a professor at the University of California, Davis for 28 years, Laky was instrumental in developing Environmental Design as an independent department (now the Department of Design). Here, she became fascinated by grids, latticework, tensile structures, strut-and-cable construction and other architectural and engineering linear assemblages. Coupled with her extensive background in textiles, she uses hand-construction techniques based in textile work to build sculptures invigorated by her attraction to the human cleverness of building things. She calls this discipline “Textile Architecture”.

“The vertical and horizontal elements of textile technology – ubiquitous in textile constructions of all sorts – underpins so much of human ingenuity about making things and led us, eventually, to the age of computers. In the context of a personal examination of our complex relationship with the world around us, my work often combines materials sourced from nature with screws, nails or ‘bullets for building’ (as the drywall screws I like are, ironically, called). The incongruity of hardware protruding from branches hints at edgy relationships as well as the flux of human interaction with nature,” says Laky.

Laky is also known for her outdoor and temporary site-specific installations, including land art works in Italy, which have all addressed nature and environmental sustainability issues. In 2008, she was commissioned by The New York Times to create sculptures for their “green” issue dedicated to Earth Day. This cover work, titled Alterations, contrasts natural apple wood and grapevine with rough industrial materials, tenuously joined by metal screws, nails, bullets and wire which figuratively, literally and symbolically represent direct and subtle messages about the interdependence of man and nature.

Laky’s works are in the permanent collections of museums including MoMA in New York, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Smithsonian. She has had solo exhibitions at Officinet Gallery, Danish Arts and Crafts Association in Copenhagen and Royal Institute of British Architects Gallery, Manchester, and has shown at San Francisco Museum of Art, Renwick Gallery, De Young Museum, and International Biennial of Tapestry in Lausanne, to name a few. She is the recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Grant and a fellow of American Craft Council. For a full list visit browngrotta.com.

For the upcoming exhibition Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber Art for Three Decades at browngrotta arts in Wilton, CT (September 12-20), Laky continues her personal examination of the complex relationships we have with the world around us and will be presenting three works – Deviation, We Turn and Traverser.

Laky’s typographical wall sculpture, Deviation, is made of apple trimmings, acrylic paint and screws. It portrays many meanings, from functioning like diacritical marks representing “Oh, Why?” to the myriad implications and emotions of the word “Oy” – the Yiddish word meaning woe, dismay or annoyance – or, if flipped, “Yo” – a slang salutation for “hello” or representing “good luck” rolling an 11 in the game of craps, the only number that always wins.

See more in our exhibition, Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber Art for Three Decades at browngrotta arts in Wilton, CT (September 12-20), http://www.browngrotta.com/Pages/calendar.php

Art & Identity: A Sense of Place

In our 2019 Art in the Barn exhibition, we asked artists to address the theme of identity. In doing so, several of the participants in Art + Identity: an international view, wrote eloquently about places that have informed their work. For Mary Merkel-Hess, that place is the plains of Iowa, which viewers can feel when viewing her windblown, bladed shapes. A recent work made a vivid red orange was an homage to noted author, Willa Cather’s plains’ description, “the bush that burned with fire and was not consumed,” a view that Merkel-Hess says she has seen.

The late Micheline Beauchemin traveled extensively from her native Montreal. Europe, Asia, the Middle East, all influenced her work but depictions of the St. Lawrence River were a constant thread throughout her career. The river, “has always fascinated me,” she admitted, calling it, “a source of constant wonder” (Micheline Beauchemin, les éditions de passage, 2009). “Under a lemon yellow sky, this river, leaded at certain times, is inhabited in winter, with ice wings without shadows, fragile and stubborn, on which a thousand glittering lights change their colors in an apparent immobility.” To replicate these effects, she incorporated unexpected materials like glass, aluminum and acrylic blocks that glitter and reflect light and metallic threads to translate light of frost and ice.

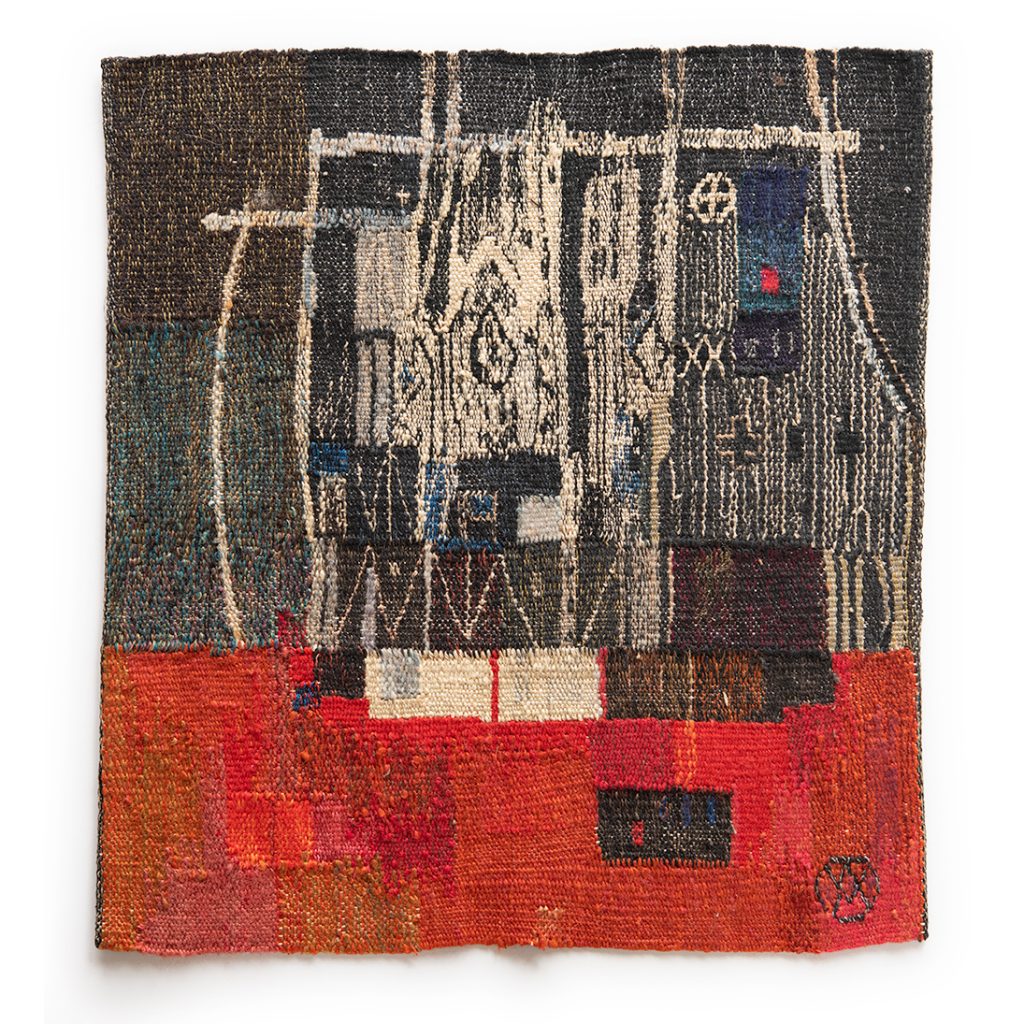

Mérida, Venezuela, the place they live, and can always come back to, has been a primary influence on Eduardo Portillo’s and Maria Davila’s way of thinking, life and work. Its geography and people have given them a strong sense of place. Mérida is deep in the Andes Mountains, and the artists have been exploring this countryside for years. Centuries-old switchback trails or “chains” that historically helped to divide farms and provide a mountain path for farm animals have recently provided inspiration and the theme for a body of work, entitled Within the Mountains. Nebula, the first work from this group of textiles, is owned by the Cooper Hewitt Museum.

Birgit Birkkjaer’s Ode for the Ocean is composed of many small woven boxes with items from the sea — stones, shells, fossils and so on — on their lids. ” It started as a diary-project when we moved to the sea some years ago,” she explains. “We moved from an area with woods, and as I have always used materials from the place where I live and where I travel, it was obvious I needed now to draw sea-related elements into my art work.”

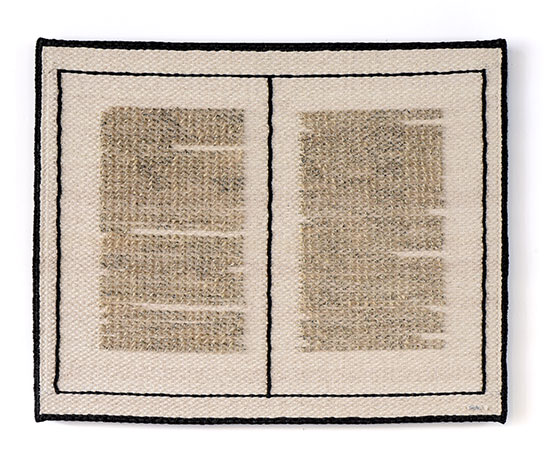

“I am born and raised in the Northeast,” says Polly Barton, “trained to weave in Japan, and have lived most of my life in the American Southwest. These disparate places find connection in the woven fabric that is my art, the internal reflections of landscape.” In works like Continuum i, ii, iii, Barton uses woven ikat as her “paintbrush,” to study native Southwestern sandstone. Nature’s shifting elements etched into the stone’s layered fascia reveal the bands of time. “Likewise, in threads dyed and woven, my essence is set in stone.”

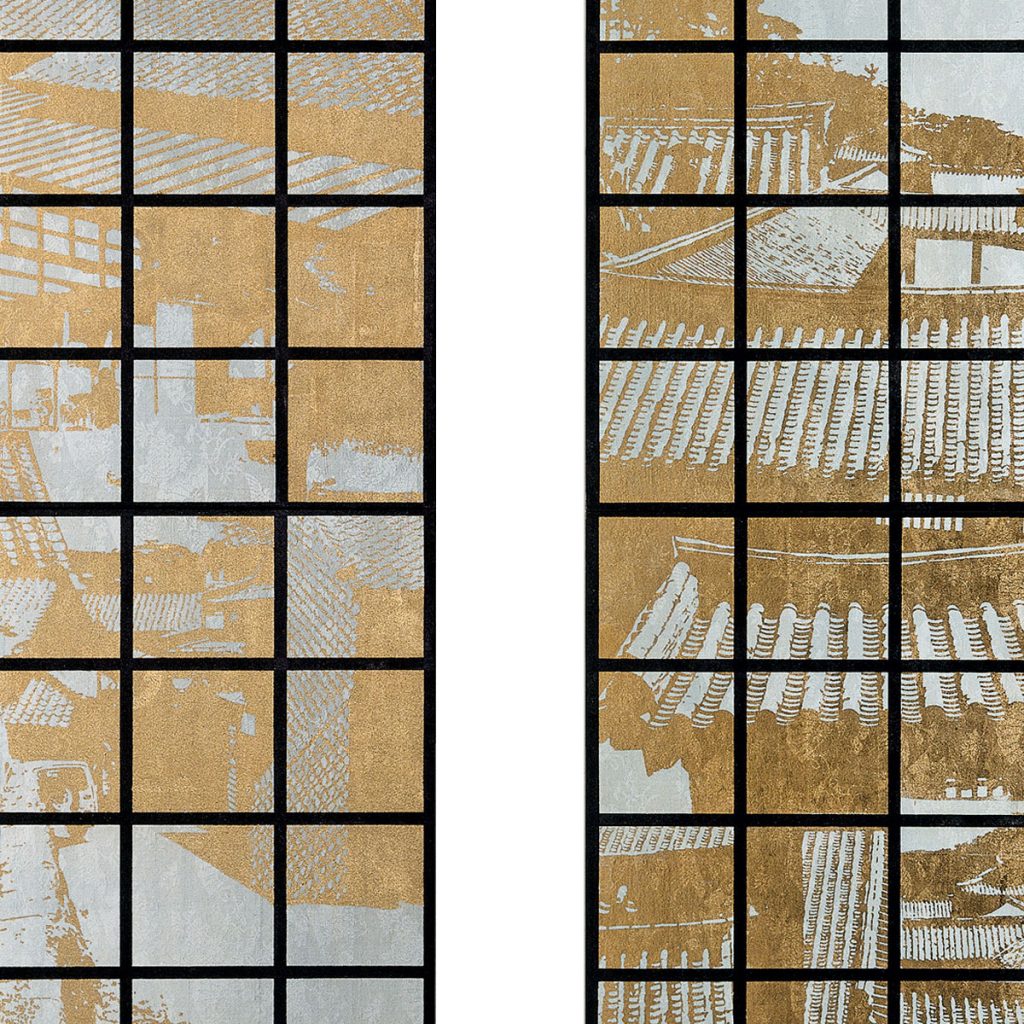

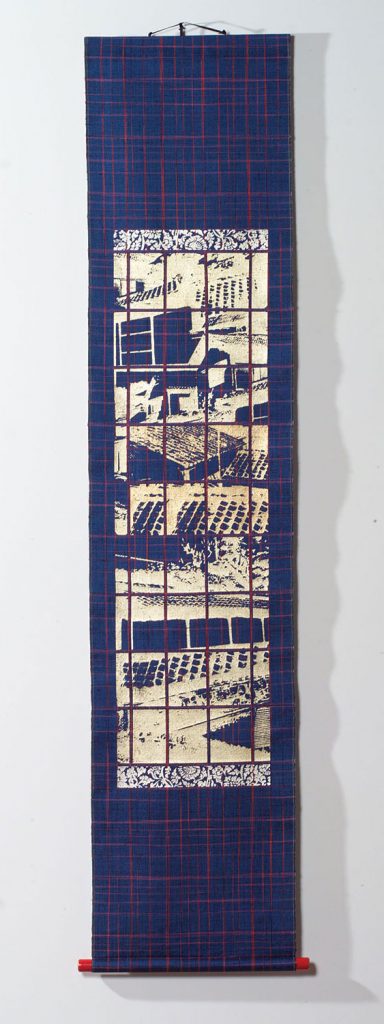

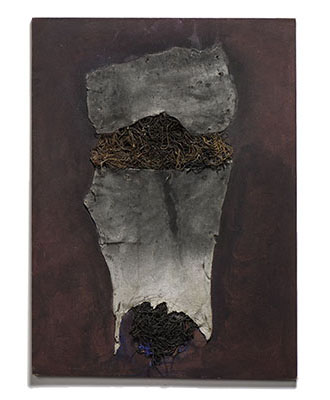

For Paul Furneaux, geographic influences are varied, including time spent in Mexico, at Norwegian fjords and then, Japan, where he studied Japanese woodblock, Mokuhanga “After a workshop in Tokyo,” he writes, “I found myself in a beautful hidden-away park that I had found when I first studied there, soft cherry blossom interspersed with brutal modern architecture. When I returned to Scotland, I had forms made for me in tulip wood that I sealed and painted white. I spaced them on the wall, trying to recapture the moment. The forms say something about the architecture of those buildings but also imbue the soft sensual beauty of the trees, the park, the blossom, the soft evening light touching the sides of the harsh glass and concrete blocks.”