We were deeply saddened to learn of the death of John McQueen last week. He was a remarkable artist. We had long admired his work from afar and over the years had placed several works that he showed at other galleries. We got to know him personally when he began to exhibit with browngrotta arts more than 15 years ago. He visited us in Wilton on several occasions and we traveled to upstate New York to see him and photograph him at work.

McQueen created three-dimensional items of twigs, branches, bark, and sometimes plastic and cardboard, all of material he harvested and collected. These objects included books, fish, birds, lions, and human figures, and vessels and structures, some basket like, others not. McQueen insisted that he was not a sculptor, but a basketmaker. Containment was a consistent interest. “Baskets connect with the definition of a container — a very broad concept. This room is a container. I am a container. The earth is being contained by its atmosphere. This is so open. I don’t need to worry about reaching the end of it.” (Quoted on the relationship in the catalog for his solo exhibition at the Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Language of Containment, in 1992).

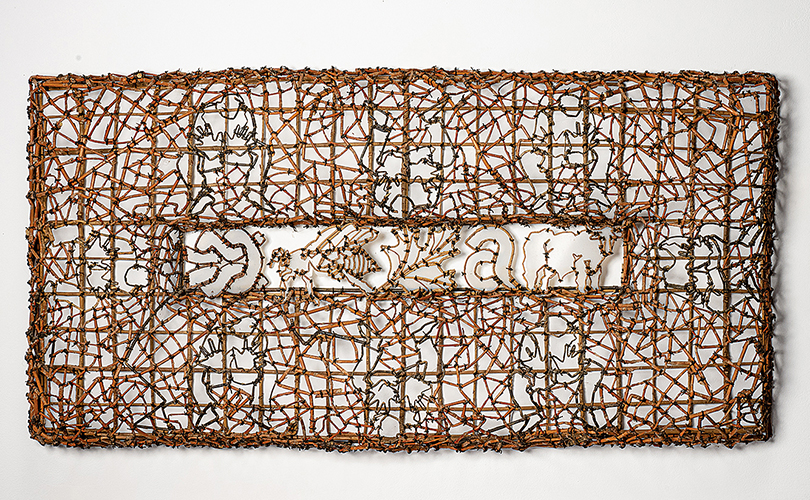

McQueen pushed the boundaries of his art form of choice throughout his working life. He created forms of pieced bark, using forms made of cardboard, “paintings” of plastic contained within frames of twigs and branches, and integrated sly and subtle messages throughout his works. Words entered his works in 1979 in Untitled #88, in which a web of words creates the container in part and conveys an idea — “Always is always a ways away.” His subsequent works abounded with puns, rebuses, and messages to be deciphered.

Man’s fruitless efforts to control nature were a frequent subject of McQueen’s art. As Vicki Halper observed in The Language of Containment, for McQueen “[t]he basket becomes an agent for investigating the fragile truce between humans and nature.” In Falling Fruit, for example, tiny stick figures are mounted beside sharks and palm trees made of twigs. We may think we can control our world, but McQueen’s camouflage-like scene suggests otherwise. As Nature does, McQueen offers surprising combinations that remind us that life is not predictable.

In 2022, McQueen decided to take on a project that would take him a year. This was an approach regularly taken by his life partner, artist Margo Mensing, who would choose a subject — generally a person — and spend a year creating artworks, poetry, performances, and multi-media installations in response. For McQueen, the result of his year’s work was 1000 Leaves, an assemblage of individually crafted structures that paid homage to trees, the source of the material that gave life to his work.

McQueen was born in Oakland, Illinois in 1943. He received a Bachelor’s degree from the University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida (where Jim Morrison was his roommate). After college he went to New Mexico where his interest in basketmaking began. Courses in weaving were a logical entry point to basketry so he enrolled in the Master’s program at Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, where he studied with Adela Akers among others. He received many awards in his career including an artist fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts, a Visual Artist Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, a United States/Japan Friendship Commission Fellowship, a Virginia A. Groot Foundation Award, the Master of the Medium Award from the James Renwick Alliance, and the Gold Medal from the American Craft Council. His work is found in numerous permanent collections, including that of the Museum of Arts and Design, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Kunstindustrimuseum, Trondheim, Norway, Detroit Institute of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

McQueen’s art stirs powerful feelings in viewers, forcing them to think about construction and words, metaphysically and literally. “McQueen’s genius lies in finding a simple declarative means of speaking about paradox, essences, and fundamental truth,” Elizabeth Broun, then-director of the National Museum of American Art observed. His genius will be greatly missed.

A rock star in the fiber world, a genius of the natural world. How I loved his basketmaking techniques that evolved into art.

Dear Friend, and great artist, we will miss you and your spirir and your devotion to our natural world.