In 1980, Norie Hatakeyama began studying basketmaking with Hisako Sekijima in Japan. Sekijima, who had studied basketry with Sandra Newman, John McQueen, and Ken and Kathleen Dalton in the US, was known for the innovative and nontraditional direction of her work. Hatakeyama felt “surprise and bewilderment, even joy,” when she encountered Sekijima’s methods. What most attracted her was Sekijima’s way of thinking was “that you must adopt an openminded approach to the basket.”

After a 40 prolific and successful years of art making, we’ve compiled Norie Hatakeyama’s thoughts on her basketry for this edition of Process Notes.

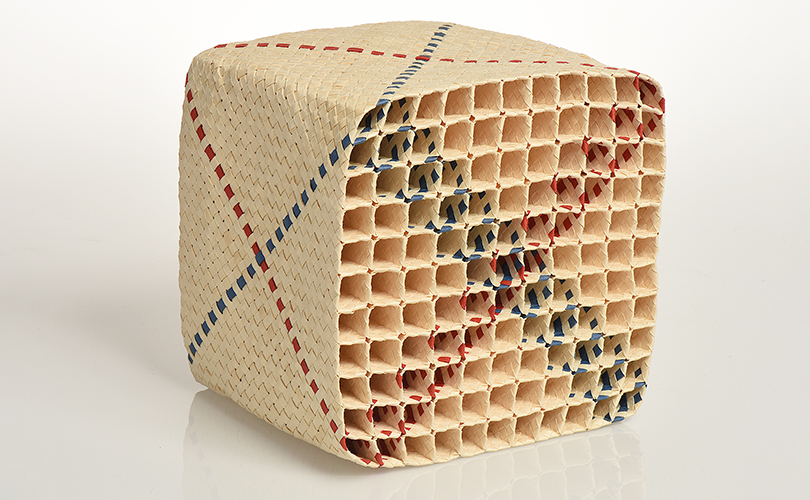

My work involves creating three-dimensional forms using basketry techniques—taking materials in my hands and weaving them together.

Basketry has a long history and has been practiced around the world using materials available in each region. The techniques themselves have changed very little over time. Because the entire process can be seen visually from beginning to end, it is easy to understand, and in principle anyone can make a basket. However, if one simply accepts and applies the technique without question, the result tends to be the same form regardless of who makes it, leaving seemingly little room for creation.

Imitating technique is one form of learning and is highly effective for improving skill, but it offers limited potential for creating new forms. As an artist, in order to develop my own approach to form-making, I try not to be bound by fixed ideas. I question existing techniques themselves and re-examine them. While maintaining a calm and attentive eye toward what is happening in the process, I consider ways to resolve the questions that arise from within it. Through this reflection, I continue weaving.

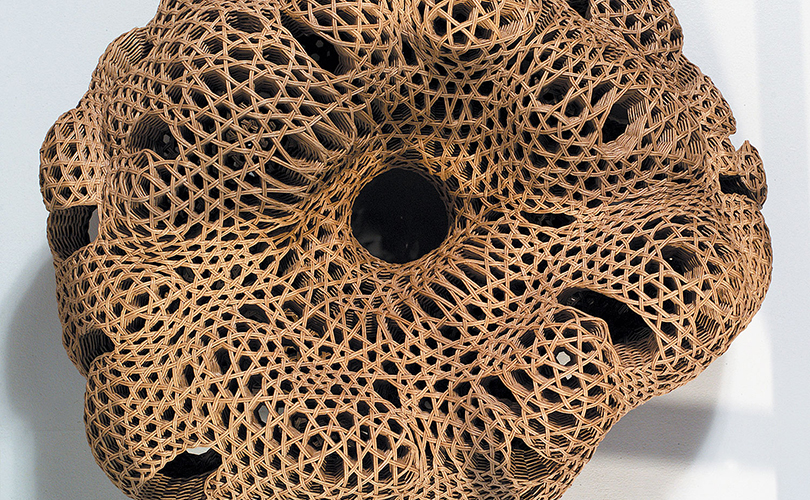

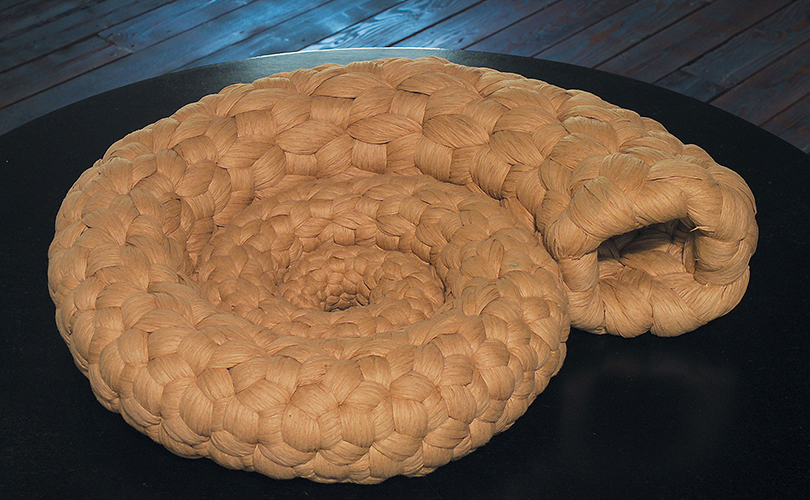

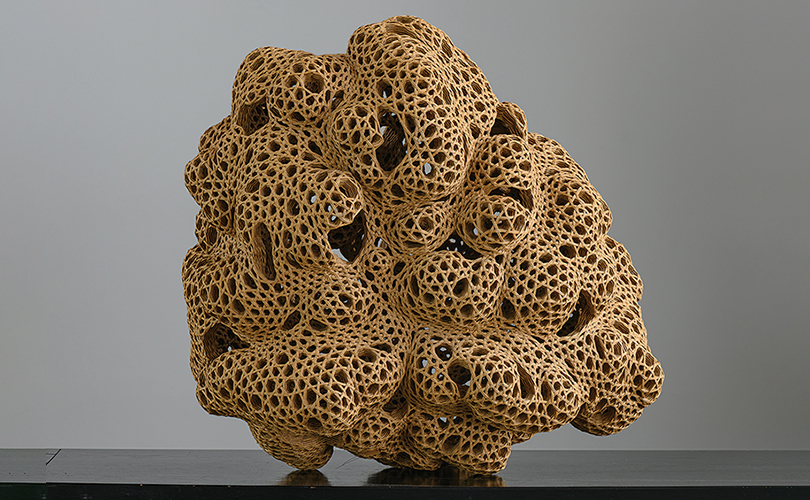

Eventually, as if a dam has burst, the forms begin to change, and shapes beyond my expectations emerge. These are not forms I intentionally designed; rather, they are forms generated by the material and the method. When the material changes, the form changes, too. The forms appear—they come toward me. I feel less that I ‘made’ them, and more that I was ‘made to make’ them. In this process, the artist’s own consciousness is altered, and self-transformation occurs.

I came to realize that the forms and formative processes of many of my works—though not created as intentional imitation—closely resemble living beings found in nature (and their generative principles). That was a moment when the activity of life and my work of making forms resonated with each other.

The accumulation of small acts of ‘re-examining methods’ has brought many realizations. That became the catalyst for the emergence of my own new approach to form-making. How rich with surprise and joy the repetition of simple actions can be. My days of creation are filled with treasures of questions and wonder. All of these rest within my hands as I continue weaving, again and again.

From a mathematical point of view, my baskets turn out to polyhedra shapes abstracted in pure geometry. However, that doesn’t mean I created the form using geometrical structure. It means the form has appeared as redefined. Geometry might be incorporated into the method, but it would seem that the forms come out from another world.

In basketry, the expanse is infinite. Making baskets is not just denying the chaotic world and one’s own inconsistency; it reaffirms those things. There is no point in asking whether my work is mathematics, art, or science, because I would say that the basketry formula is the very formula itself for nature.

Norie Hatakeyama

1999 and 2026

Norie Hatakeyama’s work Complex Plaiting Series – Connection I-9609 will be included in browngrotta arts’ up coming exhibition, Transformations: dialogues in art and materials (May 9-17, 2026).