The opening of our Fall 2025 “Art in the Barn” exhibition, on October 11, is just a few weeks away.

Despite headwinds from tariff confusion and new shipper policies, we have compiled an expansive group of works from Europe, Asia, and North and South America. The few examples below illustrate the breadth of ways that the artists in Beauty is Resistance have made aesthetic attractiveness a purposeful mode of expression.

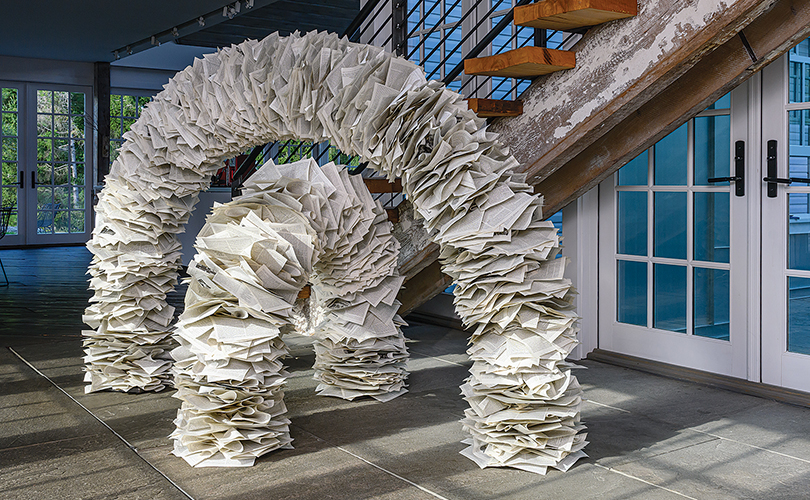

Twenty years ago, Wendy Wahl noticed that the printed and bound versions of encyclopedias were being disposed of at an alarming rate, and soon after, most encyclopedias were no longer obtainable in that format. Encyclopedias have existed for around 2,000 years. From the specific to the general, the encyclopaedia can be described as a summation of knowledge from a particular worldview. Wahl uses these discarded volumes to make art — such as the three pieces in this exhibition, Book Matched, Curiosity Under Fire, and Rebound Overlap — that brings awareness to what can happen when access to information is denied and discarded.

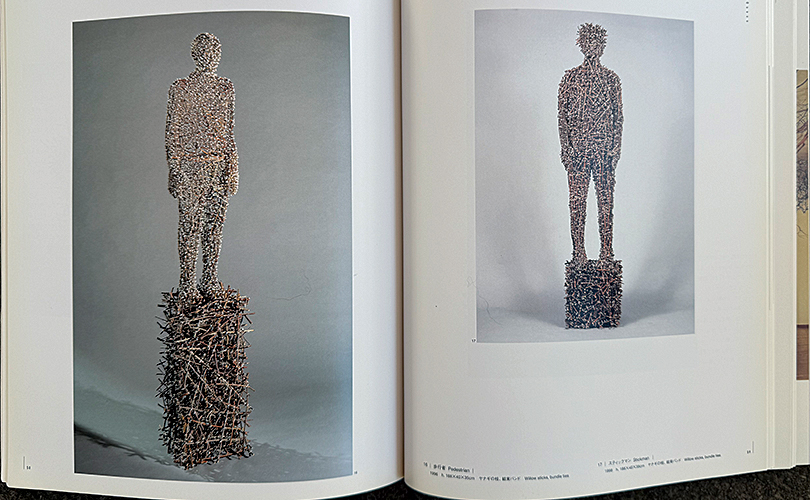

Artist, educator, and environmentalist Nnenna Okore who studied in Nigeria uses ordinary materials, repetitive processes, and varying textures to make references to everyday Nigerian practices and cultural objects. “ I am invested in changing the function, meaning, and historical or social context of my materials,” she says. “By transforming them from their original state of being and employing deconstructive and reconstructive techniques, these materials inevitably assume new lives, different personalities, and cultural significance.”

Neha Puri Dhir’s Luster of Time reflects on the beauty of aging and the stories embedded in the passage of time. The work, which involves pleating and stitch-resist dyeing on silk, reveals delicate lines and textures that evoke the growth rings of a tree or the patina formed on weathered metal. The deep circular form at the center suggests a meditative stillness, grounding the viewer amidst the rhythmic folds. Each stitch and crease becomes a quiet testimony to memory, impermanence, and transformation. “This piece celebrates time as a collaborator,” Dhir says, “turning fabric into a canvas where aging itself becomes a mark of grace and resilience.”

Masako Nakahira continues her exploration of stripes in these small but animated set of weavings. Inspired by “illusions,” a method of expression used in painting, these works are based on the theme of overlapping layers. Although this image appears to overlap visually, the layers do not actually exist in the structure. “This makes us wonder what human perception seeks between reality and illusion,” she says. “I would like to continue to question the boundary between the two through textiles.”

Join us in October to view work by these and 30+ other international artists who celebrate beauty as a form of defiance, cultural preservation, and political voice.

Exhibition Details: Beauty is Resistance: art as antidote

October 11 – 19

browngrotta arts

276 Ridgefield Road Wilton, CT 06897

Times:

Saturday, October 11th: 11AM to 6PM [Opening & Artist Reception]

Sunday, October 12th: 11AM to 6PM

Monday, October 13th through Saturday, October 18th: 10AM to 5PM

Sunday, October 19th: 11AM to 6PM [Final Day]

Safety Protocols: No narrow heels, please. We have barn floors.