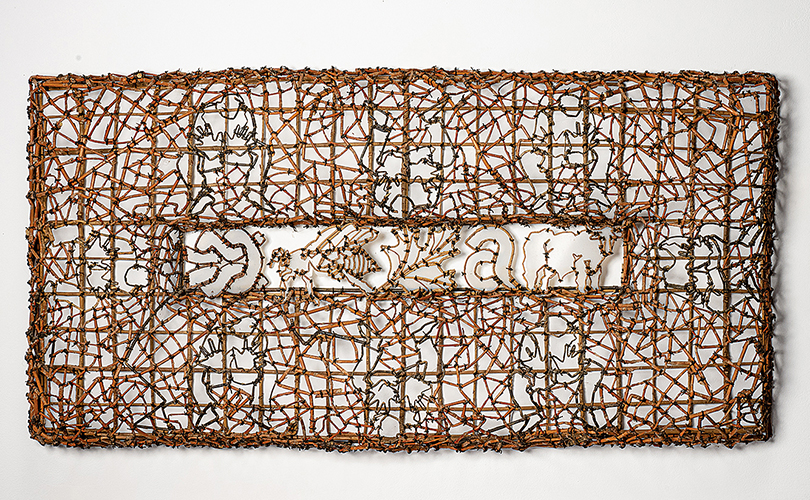

August was relaxed month for us but an active one for our New this Week features. First up was Chat by Jiro Yonezawa. Yonezawa reinterprets the traditions of Japanese bamboo craft, to create imaginative sculptural forms. Chat is from a series of works created to express conversation, communication and the acts of conveying feelings. Yonezawa wants to capture the atmosphere of these interactions. The artist says that he returned to this series, which he began a few years ago, because in today’s world, he sees conflicts and various troubles increasing. “I feel that genuine communication between people is becoming less frequent. This led me to visit this series once again, hoping that viewers can sense the atmosphere of dialogue and connection.”

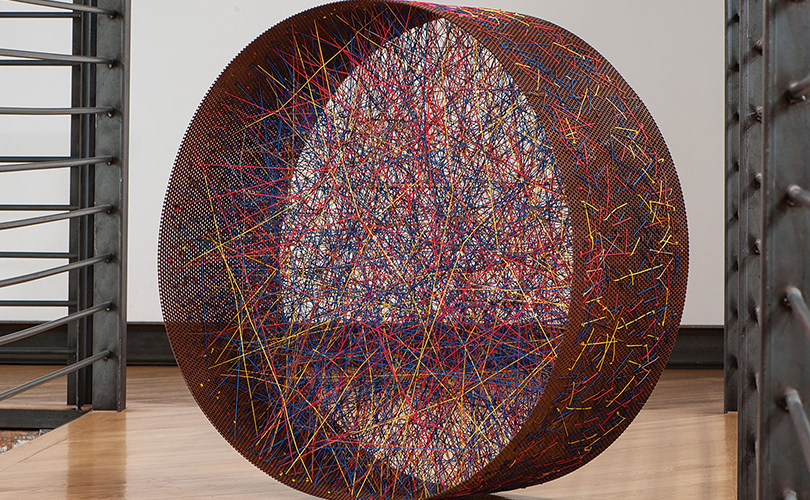

Self expression through weaving came about for Anneke Klein, she says, after she wrestled with cold hard materials during her education as a goldsmith. Her heart chose the warmth, softness, and comfort of yarns, and she retrained herself quickly in weaving techniques. Through weaving, she creates a variety of shapes, textures, and structures — looking through a symbolic lens at the everyday and the things that touch her emotionally. Her work reflects a fascination for rhythm and repetition. In Prospects for Hope, Klein uses pictograms to abstractly suggest various expressions of optimism. A widespread sense of discomfort is a concern for the artist, particularly among people she knows who are facing severe setbacks and suffering. Prospects for Hope offers a vision rooted in optimism. The work encourages viewers to see that after a dark period there always will be new perspectives.

Lizzie Farey grew up surrounded by countryside. In rural Scotland, where she developed a deep love and fascination for woodlands, coastal paths, and remote places. Through her work, primarily in willow, she seeks to immerse viewers in that landscape. In her work, Farey wants to recreate her intense feelings for the landscape. “I must capture the experience of being with nature when making a basket,” she says. Her experience has encouraged her to develop extensive knowledge of the plants featured in her work; she grows more than 20 varieties of willow.

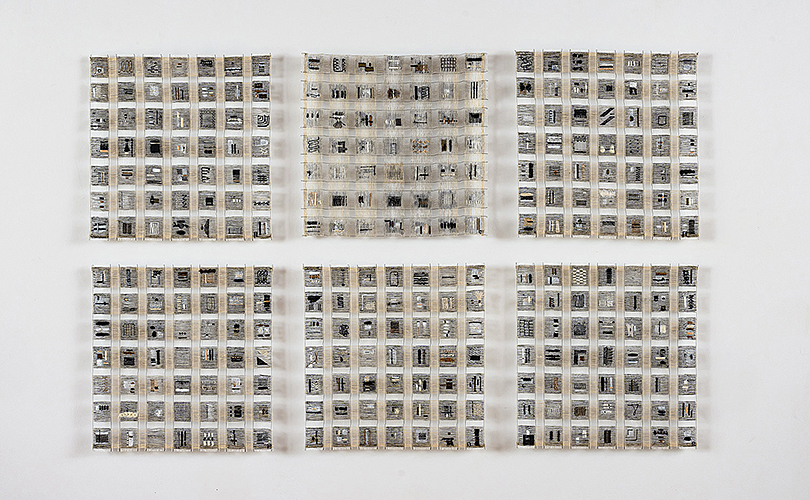

Coated in black acrylic paint, Scream by Norma Minkowitz is a crocheted object stiffened to create a plaster-like consistency, then enhanced by the application of thread. The process creates an intriguing surface, introducing a bas relief of concept, energy, and movement. Minkowitz has created highlights with paint. Her work speaks about enclosures and entrapment. Minkowitz often dwells on the cycles of death and regeneration. “As my work evolves,” she says, “one thing remains consistent: I am engaged in creating works that weave the personal and universal together.

More ahead in September …