We first met the talented and charming artist, Hiroyuki Shindo in 1995. Shindo was one of the artists in the east-west textile dialogue that Sheila Hicks crafted at browngrotta arts’ original location. Entitled Sheila Hicks, joined by seven artists from Japan, Shindo was one of the exhibition artists who created, in Hicks’ words, “strictly abstract, nonfolkloric works … Major statements in modest formats. Livable art. More than livable — inspirational and elevating, magnets of meditation.” Shindo and his wife, Chikako, came to Wilton, Connecticut from Japan, as did artist Chiyoko Tanaka, to install the exhibition with Hicks. Shindo served as an invaluable translator and witty raconteur. We learned about the virtues of cold sake, offerings made to the indigo gods, and his adventures in Broken Bow, Nebraska. (He had travelled, he told us, to Nebraska because it was where Sheila Hicks was born.)

We also learned in 1995 about Shindo’s remarkable art process. Shindo worked with indigo, which he first encountered as a student at Kyoto City University of Fine Arts in the late 1960s. An older artisan had told Shindo that he was the last of 14 generations of indigo dyers — Shindo was determined to prevent this art form’s extinction.

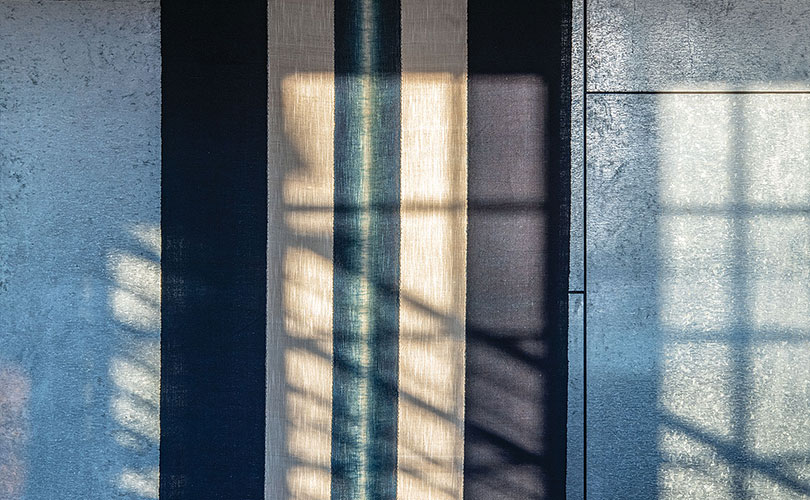

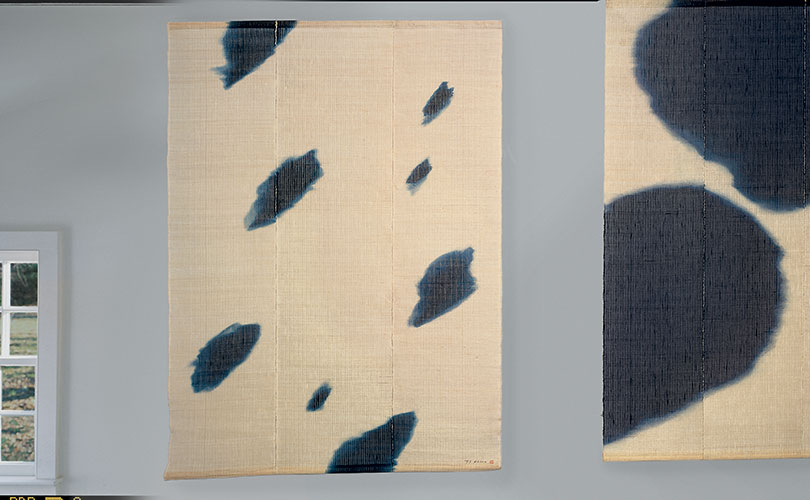

Shindo used only natural indigo for his work, which involved an elaborate ritual of his own formulation. He would first ferment the dye, pour it into a cement pool that contained pebbles. Next, he would move pebbles in a trough into the configuration he liked. Finally, he would press linen or flax into the trough of pebbles and dye, revealing the shapes and blurred edges he envisioned — from areas of nearly black to nearly invivible blue shadows. Shindo also made fascinating “thread balls” of wound thread where certain areas were highlighted with dye. As Hicks described the result, ”He is painting. He is sculpting. He is creating entire environments.” The white was as important to these works as the indigo Shindo believed. “If the white is not brilliant enough, or the undyed portion is not the right proportion, the balance is broken, and so I insist, white is as important to my work as is indigo.” Once dyed, the balls were placed in a nearby stream for rinsing, a process that is beautifully filmed in the video Textile Magicians by Cristobal Zanartu.

Shindo’s work has been exhibited widely. At the North Dakota Museum of Art, he created a series of panels responding to the flat landsape of the plains. He was among the artists included in Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and Textile Wizards from Japan at the Israel Museum of Art in Jerusalem. His work is in a large group of museum collections including the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, Museum of Arts and Design, New York, New York, and Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City. In 1997, he became a professor and head of the textile department at the Kyoto College of Art.

In 2005, Shindo founded the Little Indigo Museum, in an old thatched-roof house, in the village of Kayabuki-no-Sato, north of Kyoto. This private art museum includes examples of indigo works not only from Japan, but also from Asia, Africa, Europe, and Central America — a representation of indigo dye culture from all over the world. The collection features indigo textiles found by the artist among discarded belongings, collected during field trips, and pieces received “from people along the way.”

We are among the people he met along the way. He will indeed be missed.