“Many artists have used maps to tell wide-ranging stories about conflict, migration, identity, and social, cultural, or political networks,” notes the Museum of Modern Art in New York (Maps, Borders and Networks). “While we often regard maps as objective representations, they are in fact laden with subjective views of the world. And maps change over time. Borders and boundaries are constantly in flux, shifting with wars and politics and in response to changes in international relations.” Numerous names have been suggested for various strains of this intersection: “psychogeography,” “locative media,” “experimental geography,” “site specific art,” “new genre public art,””critical cartography,” and “critical spatial practices.” (Art and Cartography online). We coined “mapmatics” and we like it. Like the study of math, it suggests an abstract view of number, quantity, and space taken by maps in art. Like math, mapmatics may be studied in its own right or as applied in collage or sculpture.

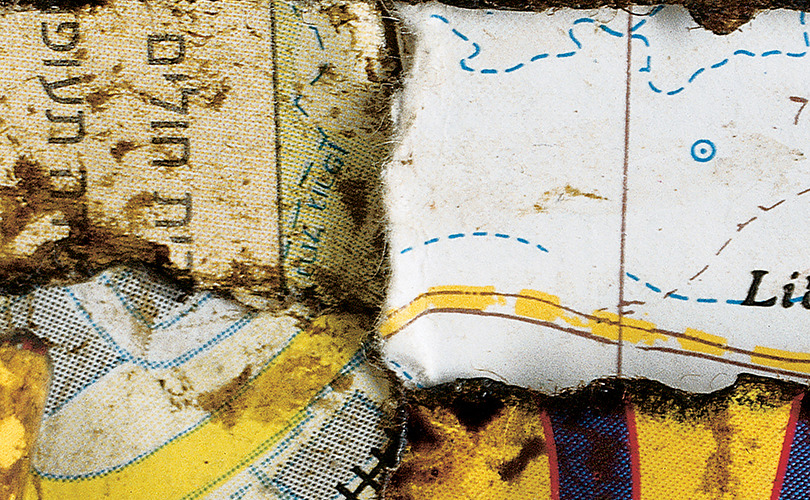

Toshio Sekiji of Japan, for example, uses maps to explore the merge of cultures in collage/weavings — as well as repurposed newspapers and book pages. His works have included weavings of maps of New York streets, and the subway system and of Jerusalem where ancient and modern cultures collide. “New stories are created atop the old,” he says, by reading the strips of papers and the areas he has enhanced, by selection and sometimes with lacquer. When the strips are woven, the result is a tapestry of almost-symbols, a tapestry that vanishes at the border of meaning.

In I Am Here, the late Marian Hildebrandt makes a personal statement about her artistic identity. Hildebrandt gathered materials for her baskets and structures exclusively from riverbeds, ravines, meadows, and woods near her home in Napa Valley, California. That process is reflected in her use of a topographical map of Napa to create this work.

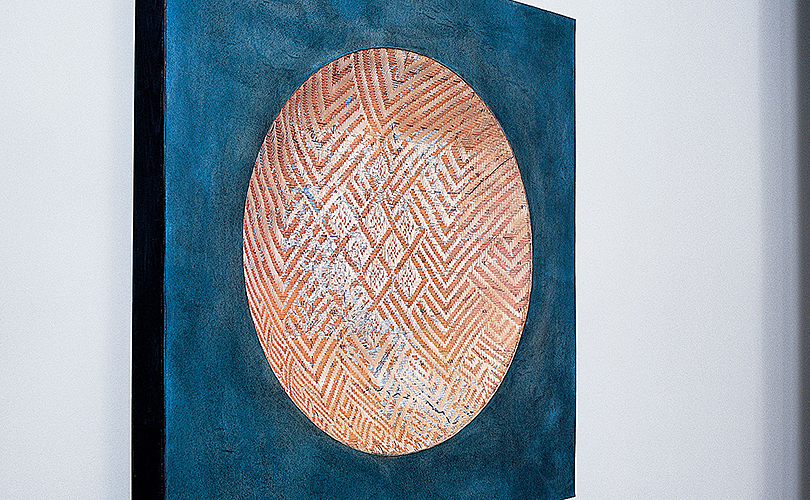

Chris Drury uses maps — preprinted and hand drawn — as a “schematic way of mapping place and experience.” In Ladakh I, he has mixedEarth-pigmented paper and maps woven into a convex bowl, mounted into paper covered board with blue water color and charcoal to document a trip there.

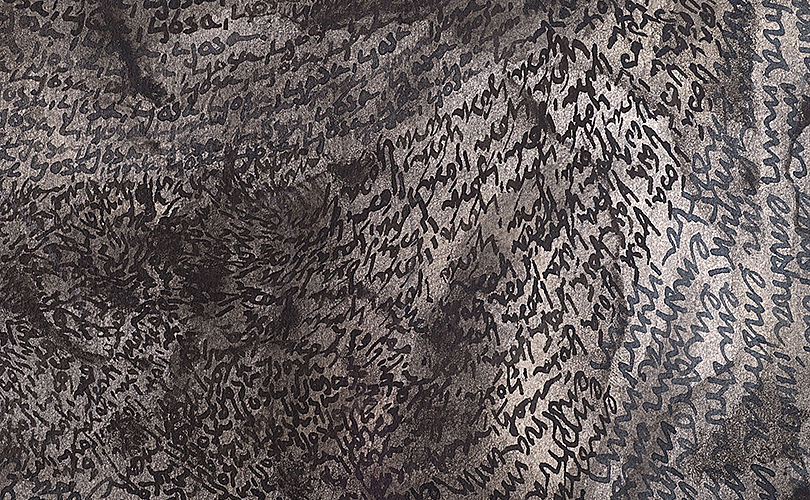

In Crossing and Re-Crossing the Rivers of Iceland, Drury used hand-written text in ink, on canvas-backed, peat-impregnated paper, to list and repeat all the rivers crossed on a six-day walk from Porsmork to Landmanalauga. “My friend Phil,” Drury explains, “a climber who had developed a heart condition, came with me on this walk. On the fourth day we were hit by a storm and waited out the night in a hut. Anchoring Crossing and Re-Crossing the Rivers of Iceland is a satellite image of that storm. The following day, we started for the next hut, crossed a cold river and climbed 2000 feet to a snow-covered plateau where the storm returned. Phil, who was cold and tired, announced he wasn’t going to make it.” He was, in fact, having a heart attack – his heart was shutting down. He swallowed pills, given him by his doctor for just such an emergency, which saved his life and made it to the hut. “The double vortex in Crossing and Re-Crossing is a pattern called a ‘Cardiac Twist,’ ” Drury says, “a term referring to blood flows in the heart. The storm we were caught in had that same pattern.”

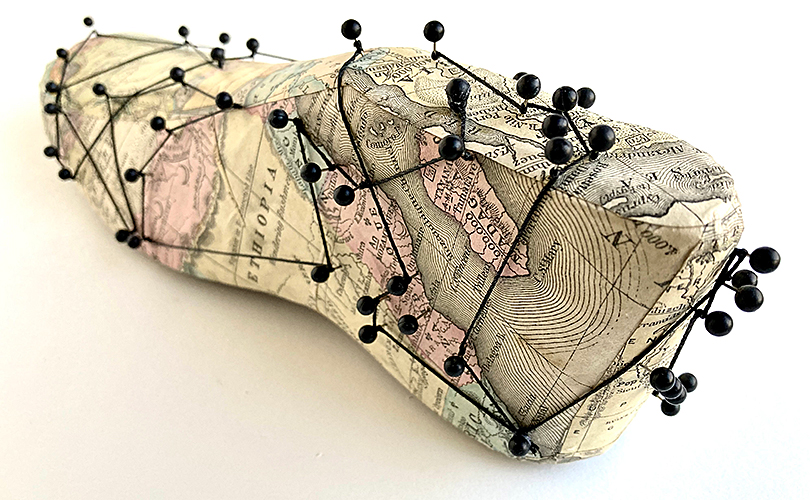

By contrast, Carole Kunstadt, a collagist, painter, book arts and fiber artist, maps a more metaphysical journey. By combining disparate found objects, ephemera, antique maps, and illustrations she aims to present new levels of involvement. “Beyond the experience of a specific space/time, we are brought to other places, fantasies and experiences through these combinations,” she writes. Such imaginings include the whimsical map-wrapped foot that makes up Migration, which leaves the viewer wondering where has it been and where it is going. Kunstadt’s work is currently on display at the Olive Free Library in West Shokan, New York in cARTography: alternate routes, through May 6th. “By altering the context, format, and purpose of a map,” the curator explains, “this group of ten artists presents a diversity of approaches that are thought provoking and visually exciting.”

Want to learn more? Visit Maps as Art an online exhibition at the University of Michigan or MoMA Learning: Maps, Borders, and Networks.

Rhonda Brown