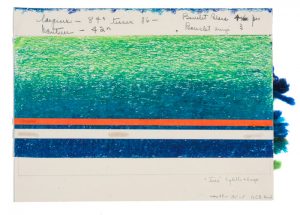

More of a mystery — the back of Lenore Tawney’s Untitled Collage, 9.125” x 9”,10/23/64. Photo: Tom Grotta

Though artists generally create artwork with the intent for just the front to be viewed, the backs of canvases and tapestries can provide collectors, curators, historians and viewers with an interesting narrative. Since the late 18th century, conservators have been paying attention to the backs of artworks. “Why?” you may ask. The answer is this: the face of a painting communicates its art, but it’s back carries the history of the artwork itself.

“On the backs of canvases, stretcher bars (the wooden framework holding the canvas in place), and the undersides of frames, careful examiners can often find inscriptions left by artists, last-ditch attempts to advocate for works once they’ve left the studio,” explains Karen Chernick of Artsy in a lengthy piece,“The Secrets Hidden on the Backs of Famous Artworks, (https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-secrets-hidden-backs-famous-artworks?utm_medium=email&utm_source=13995943-newsletter-editorial-daily-07-27-18&utm_campaign=editorial&utm_content=st-S Artists’ inscriptions serve as an important means of ensuring that the important details of a piece, such as its title, date and authorship, are preserved as the piece changes hands through time. In fact, “Versos are also frequently marked by dealers, collectors, and museums, with notations ranging from greased pencil notes to wax seals, exhibition labels, and inventory numbers,” writes Chernick. “Taken together, these markings are akin to a painting’s passport, representing its identity, travels, and even changes of address.”

However, it’s important to note that this practice is individual. There are artists who choose to provide meticulous details—notes, sewn labels, stitched informatio—and artists who leave the back of canvases or tapestries blank. For some artists, discovering provenance requires determined detective work, others offer an open book.

Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, for example, used a numbering system on that back of tapestries, which matched the meticulous files that she kept for the 640 signed works she created in her lifetime. Her files offer very detailed information about the nature of her working methods and the means by which she created and executed such commissions. Her commission for the curtain for the main hall of the National Arts Centre in Ottawa include the negotiations leading up to the contract awarded to her for the commission; original sketches documenting her various conceptions for the curtain, blueprints and plans, fabric and textile samples, diagrams relating to the means by which the design would be implemented, correspondence with craftsmen, manufacturers, and other individuals with whom she collaborated to complete the commission, and installation instructions.

The label for Mariette Rousseau-Vermette’s Joie 2 — the number links to her meticulously maintained files.

Photo: Tom Grotta.

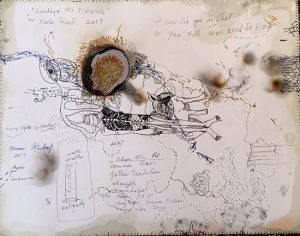

In some instances, the backs of art works can give you a peek into an artist’s artistic process. While creating their work, artists who have continually reworked canvases “may cross out bygone titles previously inscribed on stretchers, leaving hints about images cloaked beneath layers of superimposed brushstrokes.” For 20th-century artists, such as as Josef Albers, writes Chernick, the backs of canvases were the perfect place to leave explanatory appendices. Albers used the back of canvases to record detailed notes on the themes of his series. Chernick quotes Jeanette Redensek, a scholar who has reviewed hundreds of pieces of Albers’ work, used his extensive appendices to differentiate between the varying pigments used in each piece. In his series Homage to the Square, Albers methodically experimented with pigments, creating more than 2,000 variations over the course of 26 years. “When I see the backs of those paintings, I can see that he’s changed out pigments to get a yellow ochre that’s a little darker, a yellow ochre that’s a little lighter, a cadmium yellow, a cadmium yellow light. He’s playing with very fine distinctions in the colors, and so those color notes are essential,” explains Redensek. The backs of Norma Minkowitz’s works provide another example. Replete with thoughts, images, references, they provide an eye into her process.

The back for Norma Minkowitz’s Goodbye My Friend

Photo: Tom Grotta.

The information on the back of a canvas can also impact the value of a piece of art. After a piece is consigned to auction, house specialist scan the piece for indicators of authenticity and condition. In some cases, conservators use ultra-light and raking light to unveil hidden details. The extra information uncovered through this research aids collectors and conservators in proving the authenticity of a piece, therefore increasing the value.

The elements — lining, framing, notations — that restorers consider and what auction houses review once a work is consigned is described in detail in, “What the Back of a Painting Reveals About Its History,” from In Good Taste, https://www.invaluable.com/blog/painting-back/?utm_source=brand&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=weeklyblog&utm_content=blog082318.

The backs of canvases, drawings and tapestries not only provide collectors and conservators with the information needed to prove the authenticity of a work, but presents them with an opportunity to explore an uncharted area of art history.