The National Museum of Women in the Art’s new exhibition Heavy Metal comes to an end this Sunday, September 16th. Heavy Metal is the fifth installment of the NMWA’s Women to Watch exhibition series, which seeks to increase the visibility of female artists who are working in innovative ways within a wide variety of creative communities.

Why metal? Well, because “metal is a material that is typically associated with the work of men,” points out associate curator Ginny Treanor. Metal is “a material that often requires physical strength and endurance to bend, shape and mold.” Nonetheless, women have a long history of working with metal. Additionally, metal is indispensable to our everyday lives, it holds up the buildings we live and work in, forms the frame of the cars we drive every day and adorns our bodies.

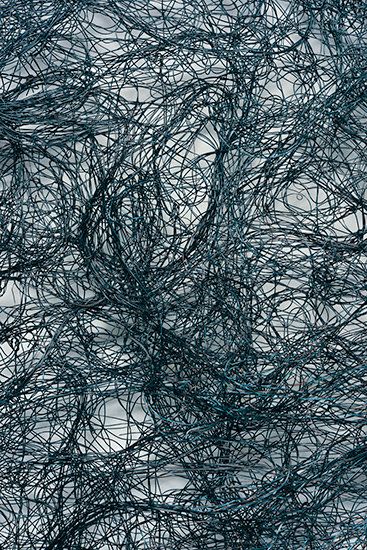

Women artists who work with browngrotta arts work in all manners of metal, including bronze, copper, steel and titanium. Kyoko Kumai is one of many browngrotta arts artists that use metal as their material. In making Blue/Green as a metaphor Kumai combined titanium tapes and stainless steel fibers to create a metal weaving. Kumai prefers using these materials because of their light, fade-resistant and hard properties which allows them to retain the image she gives them for many years.

Mary Giles preferred working with metals is because of their varying physical properties. Giles used a variety of metals in her work, including copper, tinned copper, iron, lead and brass. The malleability of these metals when heated allowed Giles to not only alter their shape but their color. Giles was able to alter the blend colors from dark to brights, which enabled her to recreate the natural gradients which she was seeing in real life.

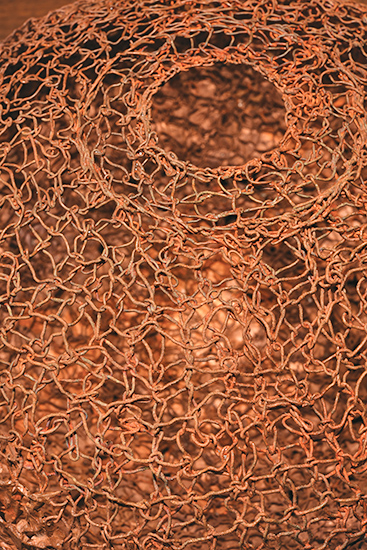

Metalworking has long been a family affair for Canadian artist Carol Fréve. Fréve followed in the steps of her grandfather, a blacksmith in Quebec in the early 1900s who forged shoes for the horses that pulled copper from mines. Over the years, Fréve has taken the traditional skills and methods her grandfather once used and experimented with them to create her own artistic process. When creating one of her wire sculptures, Fréve electro forms her copper wire knittings so they have a three-dimensional shape.

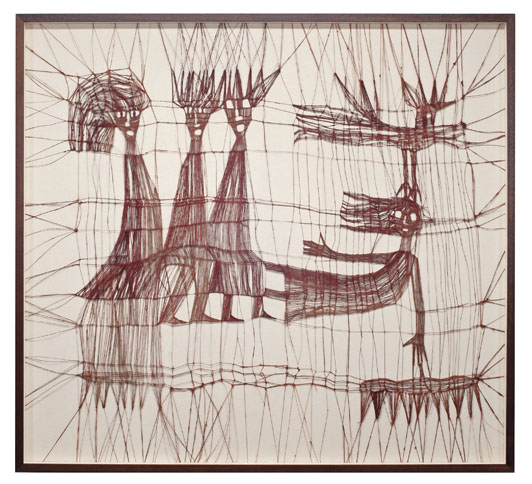

Linked copper and stainless steel wire are the materials of choice for sculptor Tsuruko Tanikawa and weaver Nancy Koenigsberg. When placed in light, the lace-like layers of wire in Koenigsberg’s Solitary Path, create an array of shadows and space. The open, yet connected nature, of the metals aid Tanikawa and Koenigsberg in exploring space, shade and light. “I am interested both in a part in light and in a part in shadow,” explains Tanikawa.“The shape of my work is made by deleting a part from a complete form.”

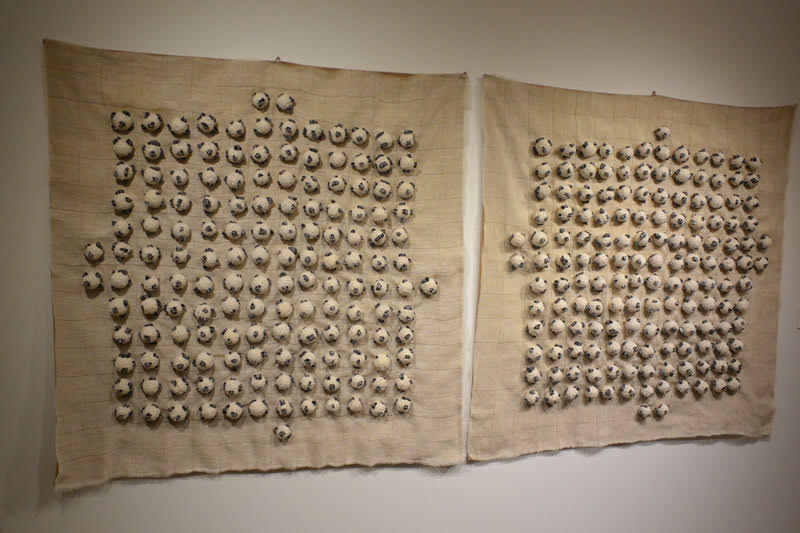

Artist Tamiko Kawata collects discarded metal materials, such as safety pins, when creating her assemblage inspired pieces. Kawata’s use of discarded safety pins as her sole material elevates the pins’ “prosaic object-roles and endows them with elegance and grandeur.” Just as Kawata breaks the utilitarian role of safety pins by using them as a material to create fine art, women are altering the masculine narrative associated with metalworking.

Heavy Metal will be on display at NMWA through Sunday, September 16th. For more information on the exhibition and the museum’s hours of operation click HERE.