As we approach the Thanksgiving holiday tomorrow, we want to take a moment to express our gratitude for the continued support from all of you. November has been a wonderful month at browngrotta arts, and we are thrilled to share the exciting developments we’ve been working on. Our highly anticipated winter exhibition Japandi Revisited: Shared Aesthetics and Influences opens on December 7, 2024, at the Wayne Art Center in Wayne, Pennsylvania. This exhibition revisits a theme we explored three years ago—how Japanese and Scandinavian artists, from Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark, draw inspiration from shared cultural and aesthetic influences. We uncovered so many fascinating stories and references that we are excited to revisit this dialogue again this winter. We hope to see you there!

In the meantime, November has been a month full of incredible features. Our New This Week series introduced the work of four incredibly talented artists: Paul Furneaux, Sue Lawty, Polly Sutton, and John McQueen. Here’s a look back at these remarkable individuals and their contributions to the world of art.

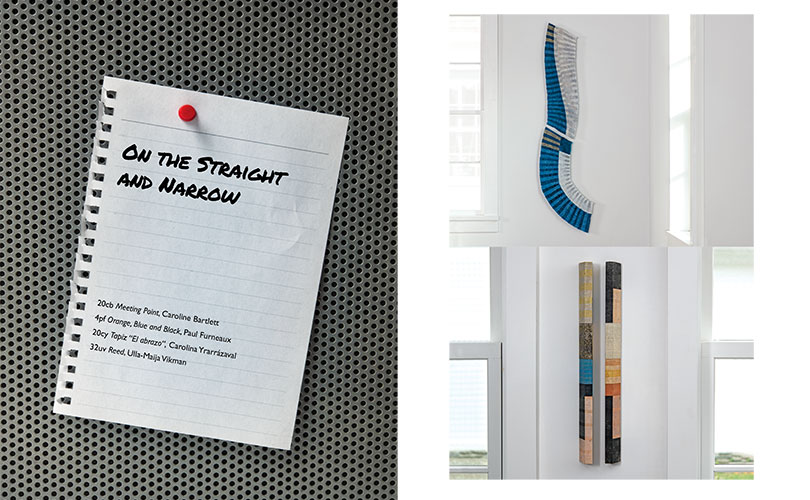

Kicking off the month, we featured the talented Scottish artist, Paul Furneaux. For over a decade, Furneaux has been exploring traditional Japanese woodblock printing techniques, particularly mokuhanga. His journey with this medium began when he received a scholarship to Tama Art University in Tokyo, where he was first introduced to the intricate art of watercolor woodblock printing. Furneaux’s work took a significant turn during a residency in Norway, which inspired a conceptual shift — moving from traditional, flat printed works to creating prints as “skins” that clothe three-dimensional sculptures. This innovative approach bridges the gap between two-dimensional and three-dimensional art, transforming the print into a more dynamic, sculptural form.

He combines his technical skill in mokuhanga with elements of texture, abstraction, and narrative, resulting in pieces that are not only visually striking but also rich in meaning. His work continues to evolve, drawing from both cultural traditions and modern interpretations, creating a unique fusion of art and craftsmanship.

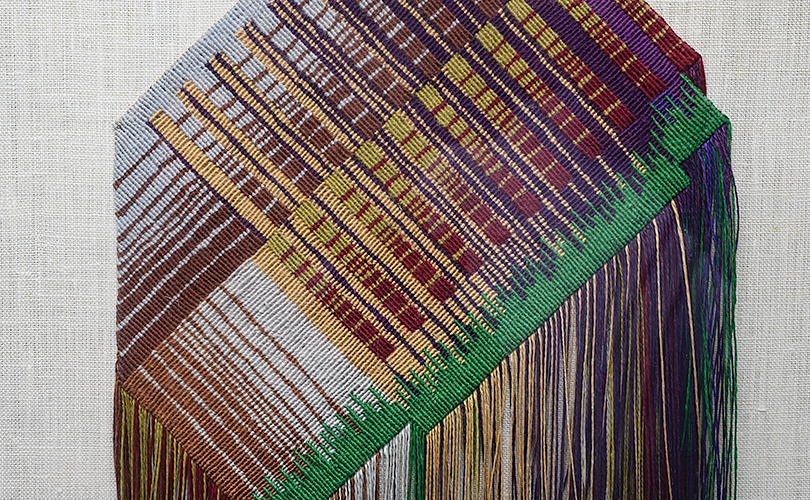

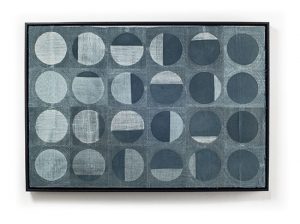

Next, we turned our spotlight to Sue Lawty, a highly experienced artist, designer, and educator whose work has been celebrated worldwide. Known for her deep emotional and physical connection to the land, Lawty’s practice explores the subtleties of material and construction to create unique textual languages through meticulous weaving. Her works often reflect a profound connection to nature, with her thoughtful use of wool and other fibers highlighting her commitment to the tactile, slow process of creation.

Throughout her career, Lawty has built a distinguished body of work exhibited internationally, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where she held a year-long residency. Her art also resides in prestigious collections, including those of the Smithsonian Museums and the University of Leeds. Lawty’s work has appeared in numerous exhibitions in the UK and beyond, including the International Triennial of Tapestry in Lodz, Poland, and the Victorian Tapestry Workshop in Melbourne, Australia. Her use of natural materials and her emotionally charged process have made her an influential figure in contemporary textile art.

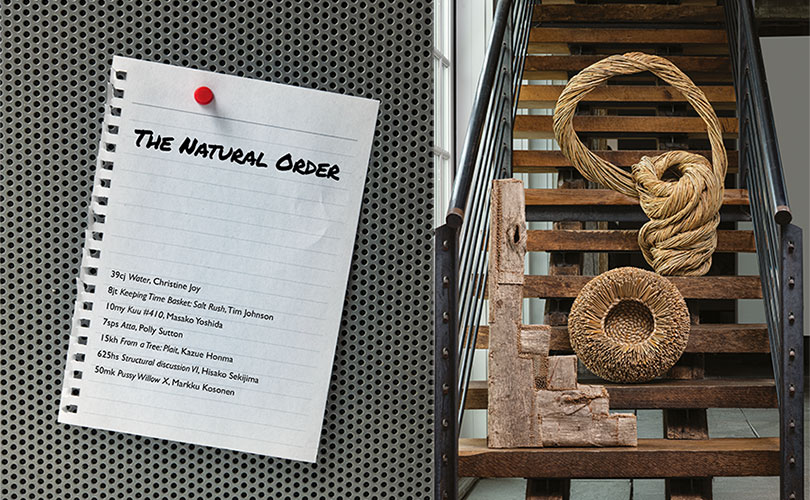

Mid-month, we highlighted the work of Polly Sutton, a talented artist known for her exceptional use of natural materials sourced from the Pacific Northwest. Sutton’s basketry work is often created from fibers of native Washington species, including cedar bark gathered from freshly logged forests and sweet grass collected from the tide flats of the Pacific Ocean. These materials are not just functional, but also deeply rooted in the natural world, often reflecting her personal connection to the land.

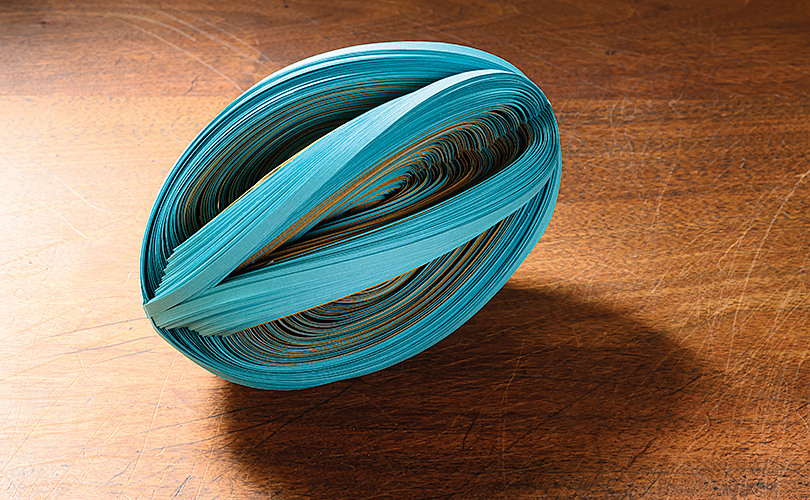

Polly Sutton is especially known for her sculptural, free-form baskets, which are created using the inner bark of Western Red Cedar trees. There are no preconceived notions about the final form; instead, Sutton’s process is one of discovery. “The work begins when I have located a logging source where, with permission, I can harvest inner bark,” she says. “The outer bark is split off in the woods, and I bring home several coils of fresh cedar bark.” Her work emphasizes pleasing, curvilinear forms, which are often asymmetrical and free-flowing, echoing the natural world that inspires her.

Finally, we spotlighted John McQueen, a renowned sculptor and artist whose work often explores the relationships between natural materials and their structural possibilities. McQueen’s piece Grapple, created in 2023, features a combination of strip willow and white pine figures. His intricate arrangements challenge the boundaries of sculpture, creating forms that feel both organic and deliberate. His approach to weaving natural materials into sculptural pieces has made McQueen a beloved figure in contemporary art, inspiring countless viewers to reconsider the role of natural elements in art.

As we wrap up November, we are incredibly grateful for your continued interest and support. Stay tuned for more exciting updates as we gear up for Japandi Revisited in December. We can’t wait to share these unique works with you and look forward to seeing you at the exhibition soon!

Art & Identity: A Sense of Place

In our 2019 Art in the Barn exhibition, we asked artists to address the theme of identity. In doing so, several of the participants in Art + Identity: an international view, wrote eloquently about places that have informed their work. For Mary Merkel-Hess, that place is the plains of Iowa, which viewers can feel when viewing her windblown, bladed shapes. A recent work made a vivid red orange was an homage to noted author, Willa Cather’s plains’ description, “the bush that burned with fire and was not consumed,” a view that Merkel-Hess says she has seen.

The late Micheline Beauchemin traveled extensively from her native Montreal. Europe, Asia, the Middle East, all influenced her work but depictions of the St. Lawrence River were a constant thread throughout her career. The river, “has always fascinated me,” she admitted, calling it, “a source of constant wonder” (Micheline Beauchemin, les éditions de passage, 2009). “Under a lemon yellow sky, this river, leaded at certain times, is inhabited in winter, with ice wings without shadows, fragile and stubborn, on which a thousand glittering lights change their colors in an apparent immobility.” To replicate these effects, she incorporated unexpected materials like glass, aluminum and acrylic blocks that glitter and reflect light and metallic threads to translate light of frost and ice.

Mérida, Venezuela, the place they live, and can always come back to, has been a primary influence on Eduardo Portillo’s and Maria Davila’s way of thinking, life and work. Its geography and people have given them a strong sense of place. Mérida is deep in the Andes Mountains, and the artists have been exploring this countryside for years. Centuries-old switchback trails or “chains” that historically helped to divide farms and provide a mountain path for farm animals have recently provided inspiration and the theme for a body of work, entitled Within the Mountains. Nebula, the first work from this group of textiles, is owned by the Cooper Hewitt Museum.

Birgit Birkkjaer’s Ode for the Ocean is composed of many small woven boxes with items from the sea — stones, shells, fossils and so on — on their lids. ” It started as a diary-project when we moved to the sea some years ago,” she explains. “We moved from an area with woods, and as I have always used materials from the place where I live and where I travel, it was obvious I needed now to draw sea-related elements into my art work.”

“I am born and raised in the Northeast,” says Polly Barton, “trained to weave in Japan, and have lived most of my life in the American Southwest. These disparate places find connection in the woven fabric that is my art, the internal reflections of landscape.” In works like Continuum i, ii, iii, Barton uses woven ikat as her “paintbrush,” to study native Southwestern sandstone. Nature’s shifting elements etched into the stone’s layered fascia reveal the bands of time. “Likewise, in threads dyed and woven, my essence is set in stone.”

For Paul Furneaux, geographic influences are varied, including time spent in Mexico, at Norwegian fjords and then, Japan, where he studied Japanese woodblock, Mokuhanga “After a workshop in Tokyo,” he writes, “I found myself in a beautful hidden-away park that I had found when I first studied there, soft cherry blossom interspersed with brutal modern architecture. When I returned to Scotland, I had forms made for me in tulip wood that I sealed and painted white. I spaced them on the wall, trying to recapture the moment. The forms say something about the architecture of those buildings but also imbue the soft sensual beauty of the trees, the park, the blossom, the soft evening light touching the sides of the harsh glass and concrete blocks.”