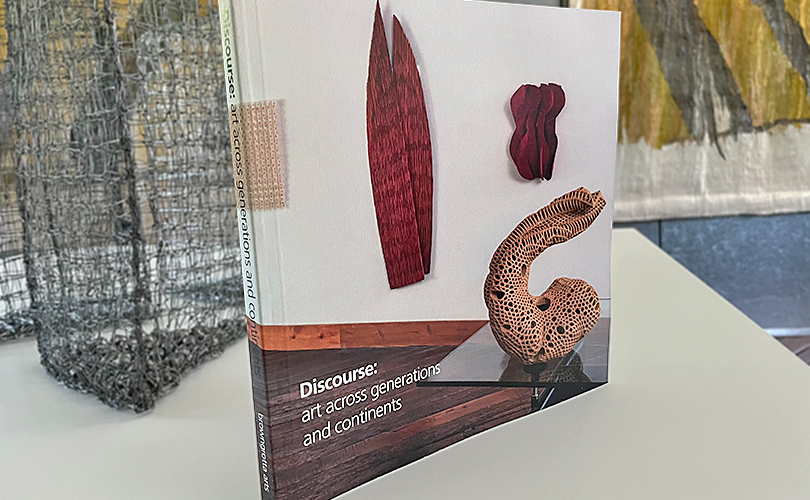

Between exhibitions and catalog production we — Tom and Rhonda at browngrotta arts — try to get out and take in some art and entertainment. This October and November are no exception. We’ve been able to visit five exhibitions over the last few weeks. Three of them close shortly — on Sunday, the fourth in December. A sixth that we recommend is open until next May. We urge you to get out to see them while you can.

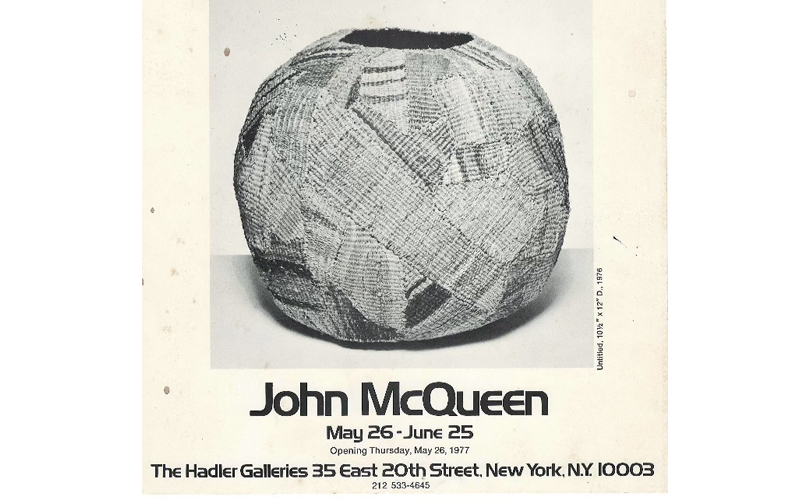

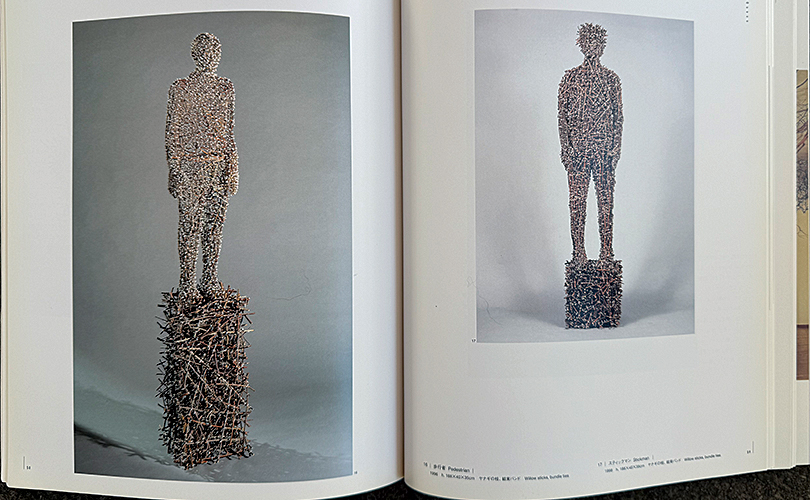

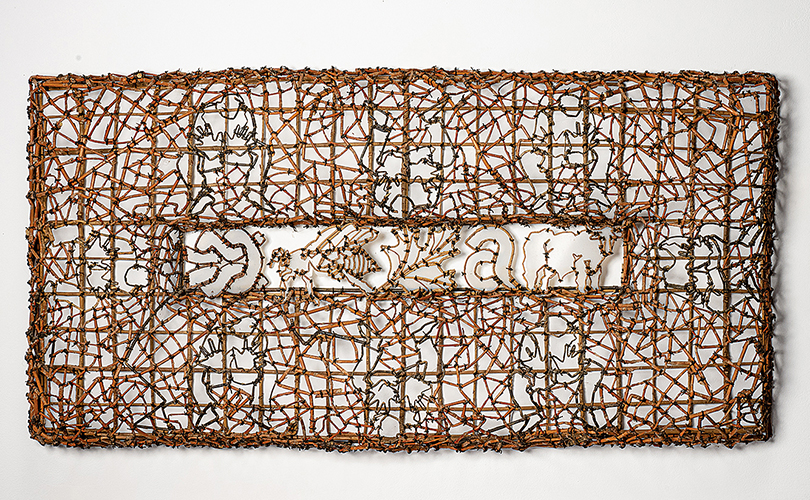

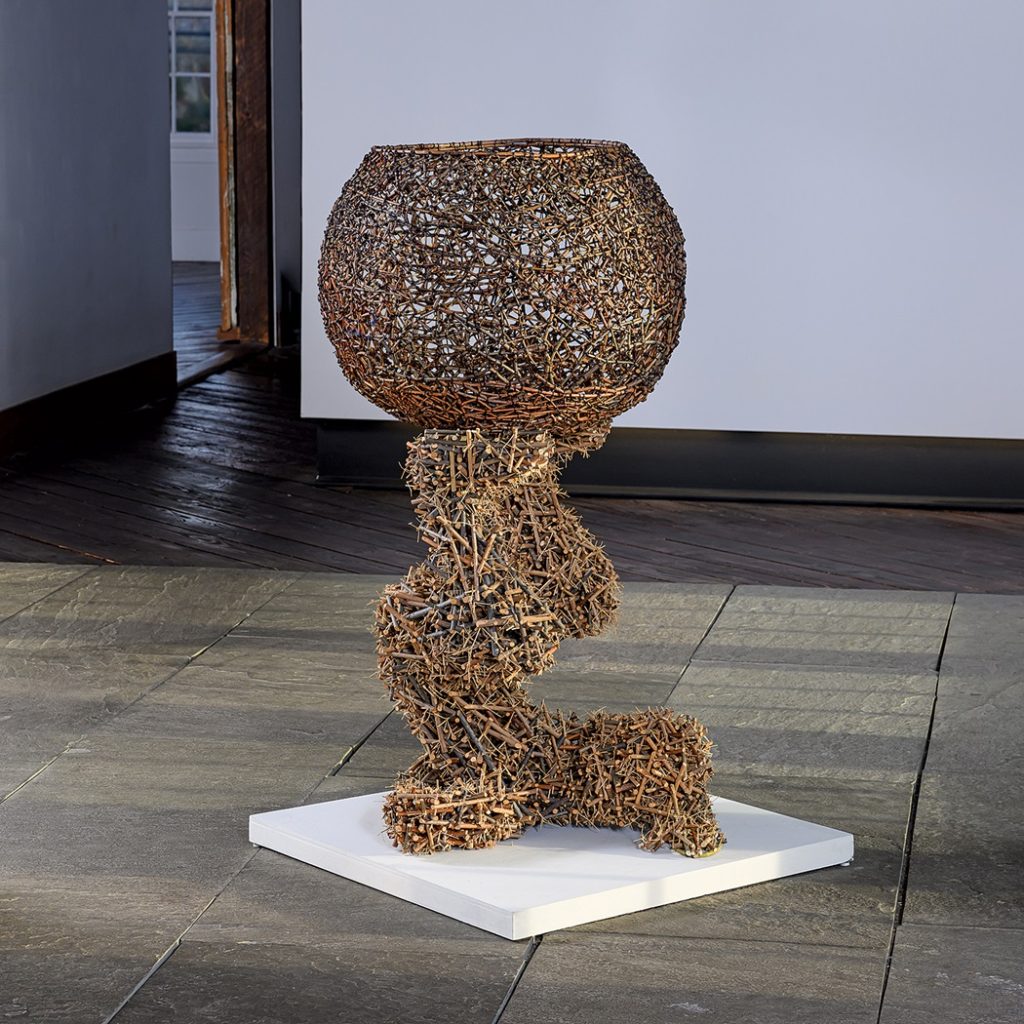

John McQueen Memorial Exhibition

The Tang Museum

Skidmore College

Saratoga Springs, NY

Through November 9th

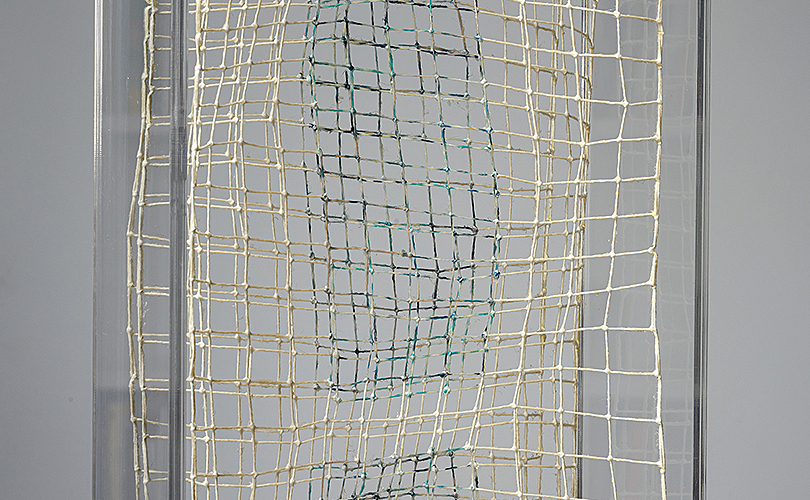

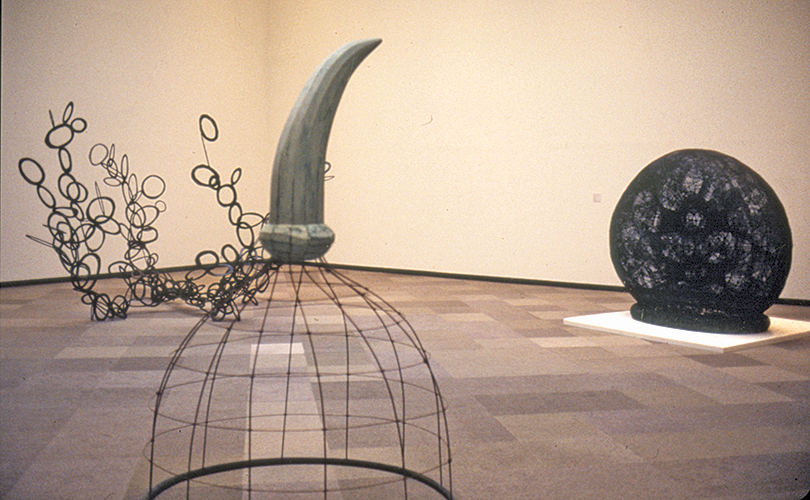

In honor of John McQueen (1943-2025), the Tang presents the John McQueen Memorial Exhibition from November 2–9. McQueen was a conceptual fiber artist whose work was featured in the Tang exhibitions Affinity Atlas (2015) and The World According to the Newest and Most Exact Observations: Mapping Art and Science (2001). The works selected for the Memorial exhibition include McQueen’s first basket from 1975, Caught Out, a self portrait completed 35 years later, and, A Tree and its Skin. a reflective diptych sculpture that was among the artist’s favorites.

Crux of the Matter: Work by Margo Mensing and Sayward Schoonmaker

The Schick Art Gallery

Skidmore College

Saratoga Springs, NY

Through November 9th

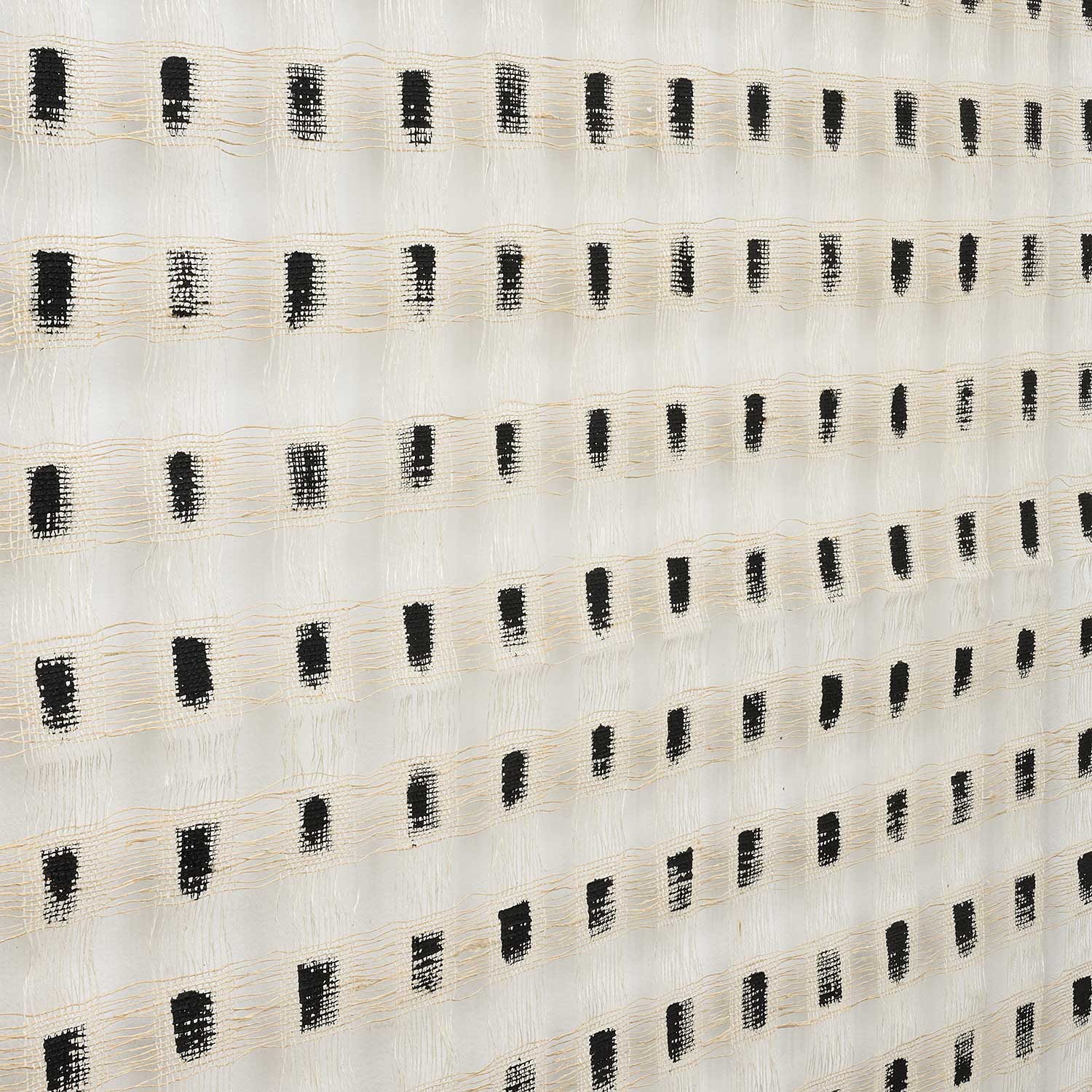

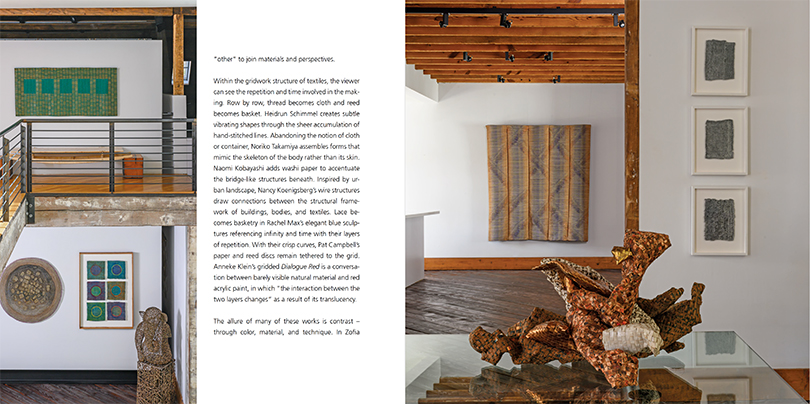

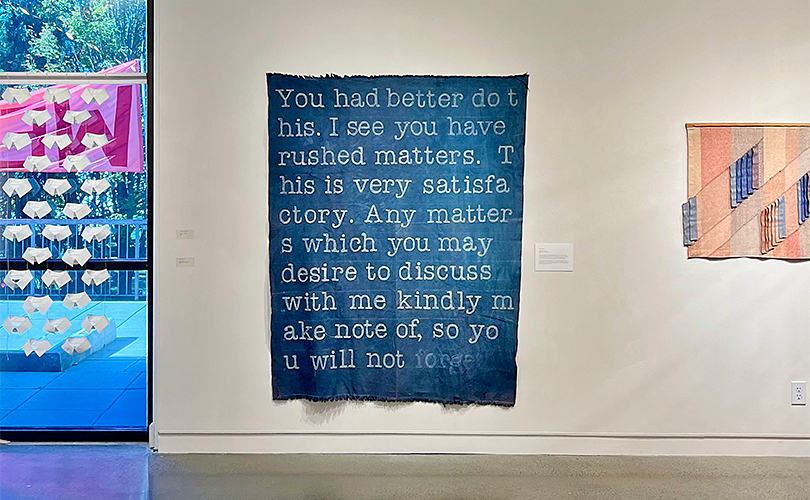

Crux of the Matter presents work by Margo Mensing, (1941 – 2024), Skidmore College Fiber Arts professor, interdisciplinary artist and poet and Sayward Schoonmaker, Skidmore ’06, interdisciplinary artist, writer, and former student of Mensing. “Both artists play with language,” the Art Gallery notes, “using subtle humor as underpinning, and both approach their work through a conceptual lens, starting with an idea and then finding the physical form to best serve it.” Mensing’s works range from weavings and quilts to her sculptural response to Ghiberti’s 15th Century Gates of Paradise, monumental bronze doors that feature ten Old Testament scenes in square panels. Mensing’s wooden doors, also monumental, feature ten household tips (such as, “Tenderize tough meat in 1 Tbsp vinegar and 1 pint water”) each incised in a square linoleum panel.

As Mensing’s son, J. Shermeta notes, her magnum opus was her “Dead at” series. Each year beginning on her birthday, October 4th, Mensing created a presentation, or a performance centered on the life and accomplishments of a famous person who died at her current age. Starting with J Robert Oppenheimer at age 63 in 2004, Margo created artwork, poetry, and organized group performances about the lives and work of Joan Mitchell, Elizabeth Bishop, Denise Levertov, Walt Disney, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Donald Judd ,and Louis Armstrong. To celebrate the life and magic of Louis Armstrong, for example, Mensing choreographed STOPTIME: Louis Armstrong Festival, bringing together musicians, artists, and performers to create over a dozen events from 4 to midnight on July 6, 2011. The Horns of Hudson band played, art teachers hosted a “Rhythm! Color! Collage!” workshop for kids, tap dancers performed and joy–inspired by the music of Louis Armstrong–was shared by all.

The Schick exhibition includes a wide range of thought-provoking works, early abstract weavings, the lovely lyrical machine-embroidered poem, you had better do this, items from the Dead at series and from other of Mensing’s projects including a group of glass pipes created as part of A Very Liquid Heaven, a multimedia installation and performance event that examined science and the universe. Also included in Crux of the Matter, are intriguing works by Sayward Schoonmaker. As the Art Center describes the collection, “from poems written in letters formed by pencil shavings, to Slice, a table with a glittering black surface interrupted by slivers of white substructure, she employs exquisite craftsmanship throughout. Her works feel like unadorned truths, simultaneously urgent and familiar, plainly-stated and enigmatic.”

Vietnam: Tradition Upended

Flinn Gallery

Greenwich, CT

Through November 9th

In collaboration with the Art Vietnam Gallery in Hanoi, the Flinn Gallery has organized Vietnam: Tradition Upended. The exhibition was curated by Debra Fram and Barbara Richards, who have worked with browngrotta arts on previous exhibitions at the Flinn, and Suzanne Lecht from Art Vietnam Gallery. The exhibition’s origins are several years old. Fram and Richards had travelled to Vietnam in 2019 and in Hanoi met Lecht, who it turned out, had lived in Greenwich on the 80s. The three remained in contact and over the next four years, Vietnam: Tradition Upended took shape. The exhibition features nine interdisciplinary artists who work in a variety of mediums and styles. We were excited by the diversity on display and particularly taken by the mixed media works of Nguyen Cam (b.1944, Haiphong, Vietnam) and the calligraphic statements of Pham Van Tuan (b.1979, Thanh Hoa province, Vietnam), 35 years his junior.

As The Flinn notes, the artists in Vietnam: Tradition Upended all take time-honored traditions and materials and rework them in a modern context, acknowledging the past while simultaneously breaking away. With 2025 marking exactly half a century since the end of the Vietnam War, and 30 years since the normalization of relations between Vietnam and the U.S., this is an opportune time to acquaint ourselves with the art and culture of a country that has undergone extraordinary change; a country with one of the most interesting and vibrant art scenes in Southeast Asia.

Stitching Time: The Social Justice Collaboration Quilts Project

Fairfield Gallery Art Museum/Walsh Gallery

Fairfield, CT

Through December 13, 2025

Stitching Time features 12 quilts created by men who are incarcerated in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola Prison. We listed the exhibition here a few weeks ago, but having the chance to see the creativity and careful creation of these works in person was a treat. These works of art, and accompanying recorded interviews, tell the story of a unique inside-outside quilt collaboration. The exhibition focuses our attention on the quilt creators, people often forgotten by society when discussing the history of the U.S. criminal justice system. Also on view in the gallery is Give Me Life, a curated selection of strong works from women artists presently or formerly incarcerated at York Correctional Institution, a maximum security state prison in Niantic, Conn., courtesy of Community Partners in Action (CPA). The CPA’s Prison Arts Program was initiated in 1978 and, operating since 1875, it is one of the longest-running projects of its kind in the United States. The quilts and CPA artworks are poignant, hopeful, and often aesthetically impressive. If you can’t visit by December, check out the exhibition’s website where you’ll find images, videos, and a flip-through catalog.

Jeremy Frey: Woven

The Bruce Museum

Greenwich, CT

Closed

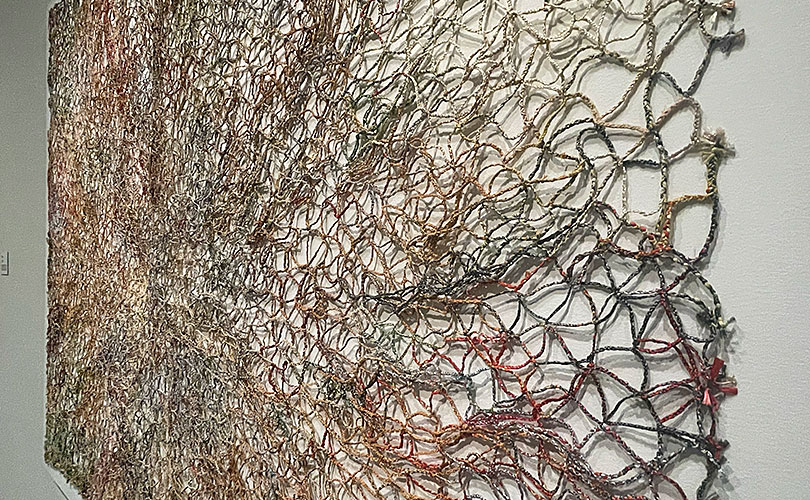

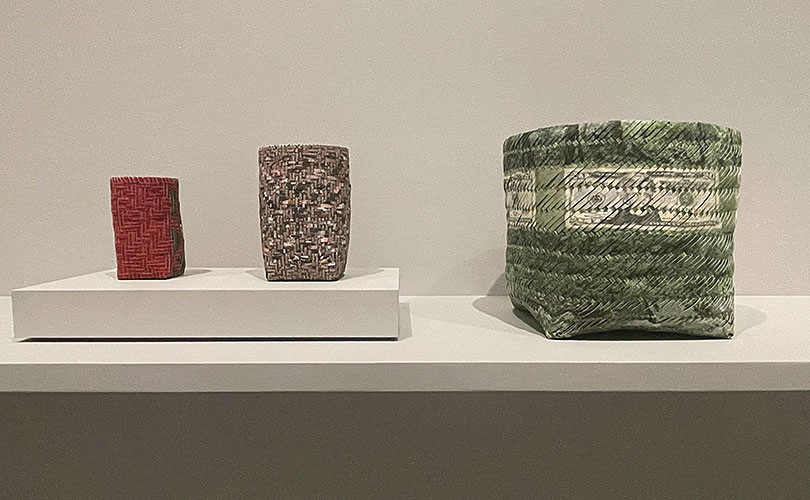

We visited Jermey Frey: Woven at the Bruce Museum just before it closed at the end of October. Frey’s virtuosity as a seventh-generation basketmaker, steeped in the Passamaquoddy tradition, was clearly evident in this remarkable retrospective. However, we were also excited and surprised to see Frey’s prints, which were striking. The exhibition had traveled from the Portland Museum of Art and if you missed it in Maine or Greenwich, there are many resources you can access to see the works that were included and learn about Frey’s meticulous process. There are images of 18 works and links to several articles from ArtDaily to The New York Times on the PAM website. There are also links to videos about the artist.

Uman: After all the things

The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

Ridgefield, CT

Through May 10, 2026

We have not had a chance to visit Uman: After all the things at the Aldrich Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut but we will. As the Museum observes, “Uman’s practice, which spans painting, works on paper, murals, sculpture, and glass, is about color that is felt and content that is experienced. Under the influence of memories, dreams, and change, her visual language is intuitive, multilayered, adaptable, and free; neither exclusively abstract nor metaphorical, it proliferates in the indeterminate and transcendent.” Uman says that her work “offers an escape …. [m]y work is its own activism.” She wants her work to “feel good for the audience.” This is an approach also taken by some of the artists in browngrotta arts’ recent exhibition, Beauty is Resistance: art as antidote. We look forward to being engaged, uplifted, and inspired.

Hope you’ll get a chance to view one or more of the exhibitions, in-person or online.