We are off to spend some of August in Maine.

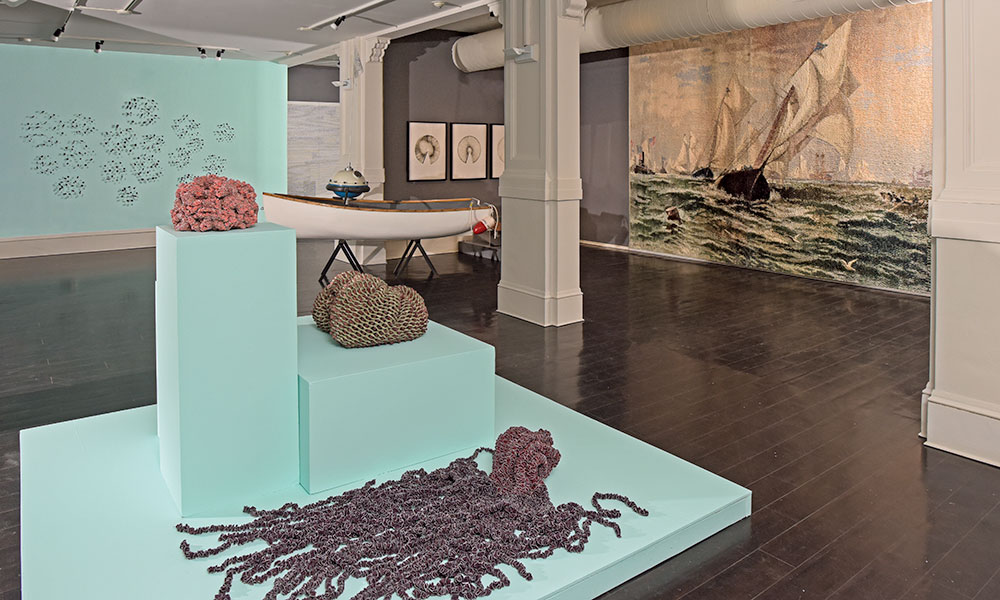

We are using this week’s arttextstyle to share some images of art that reflects some of our favorite things about the place.

Fish would be one. Watching, catching, and eating them.

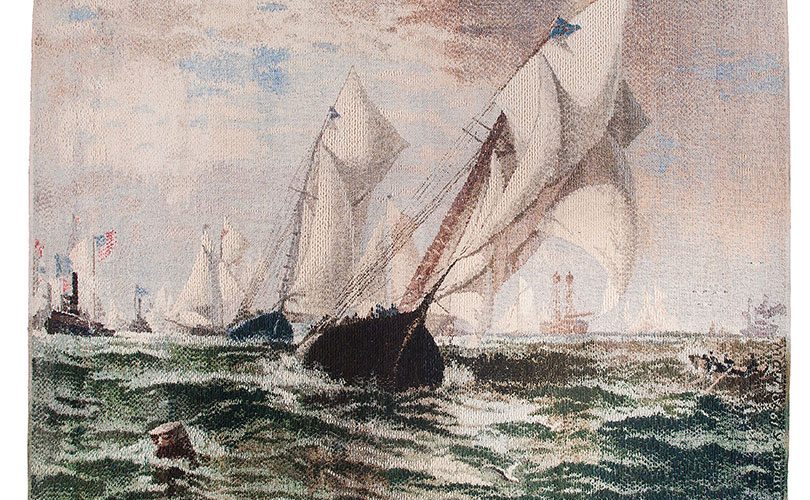

Water travel is another. We love to watch boats and kayak.

We love to watch boats and kayak.

We’ll be back next week with Art Assembled.

Happy Summer!!

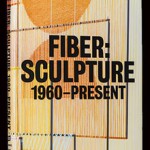

Books Make Great Gifts 2016

Another year of widely divergent books. Art, biology, history and biography are all represented in the answers we received to the questions we asked of artists that work with browngrotta arts: What books cheered you? Inspired you? Provided an escape?

Dona Anderson, wrote that she is reading Herbert Hoover: A Life by Glen Jeansonne (NAL, New York, 2016) who calls Hoover the most resourceful American since Benjamin Franklin. “I recently had a birthday and remember that my mother went to vote on the day I was born, November 6th, and she voted for Herbert Hoover. Consequently, I started to think about what the political atmosphere was like then — as ours was so crazy and even more so now. When I went to the library in October, the Hoover book was brand new and it appealed to me.” Rachel Max is reading Materiality, edited by Petra Lange-Berndt (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2015), one of the latest additons to the Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art series. It’s a fantastic series. Each volume in the series focuses on a specific theme and contains many thought-provoking essays from theorists and artists. Materiality not only addresses key geographical, social and philosophical issues, but it also examines how artists process and use materials in order to expand notions of time, space and participation. As the publisher notes, “this anthology focuses on the moments when materials become willful actors and agents within artistic processes.” Max has also been dipping into the diaries of Eva Hesse. “They are extremely private and were never meant for publication. But, as a huge fan of her work it is interesting to read her thoughts,” Max writes.

Rachel Max is reading Materiality, edited by Petra Lange-Berndt (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2015), one of the latest additons to the Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art series. It’s a fantastic series. Each volume in the series focuses on a specific theme and contains many thought-provoking essays from theorists and artists. Materiality not only addresses key geographical, social and philosophical issues, but it also examines how artists process and use materials in order to expand notions of time, space and participation. As the publisher notes, “this anthology focuses on the moments when materials become willful actors and agents within artistic processes.” Max has also been dipping into the diaries of Eva Hesse. “They are extremely private and were never meant for publication. But, as a huge fan of her work it is interesting to read her thoughts,” Max writes.

Nimura’s skillful crafting of a can’t-put-it-down narrative of their experiences on two sides of the Pacific is a vividly rich visual, as well as historical, account. She produced for the reader, through captivating descriptions illuminating the startling differences between these two very different cultures, the contrasting worlds we could easily visualize.

Stacy Shiff, Pulitzer Prise-winning author of Cleopatra wrote: “Nimura reconstructs their Alice-in-Wonderland adventure: the girls are so exotic as to qualify as ‘princesses’ on their American arrival. One feels “enormous” on her return to Japan.” It is just this Alice-in-Wonderland aspect of their story that caught my imagination. As in Louis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it is the environment and the material culture that sets the stage for remarkable events. The tangible aspects of two vastly contrasting cultures – intellectually, technically, behaviorally and in terms of the accoutrements of every day life, express well the often conflicting, peculiar and unexpected events in the girls’ lives. The girls move from Japanese clothing, furniture and customs to western style and then back again feeling more comfortable in western settings than in their birth homes kneeling on the floor and lavishly swathed in yards and yards of embroidered silks.

In the late 19th century the US was bursting with inventions and change. Planning begun in the 1850s for the Chicago World’s Fair was well under way, ushering in the Gilded Age of rapid industrial growth, design innovation and expansion of popular culture. A startlingly appropriate time for the girls’ cultural experiment to take place. Nimura, who moved to Japan for three years with her Japanese/American nesei husband, was adept at utilizing her keen sense of design and broad knowledge of the two disparate material cultures. She skillfully brought to life the vast differences between the two civilizations through masterful and insightful descriptions of clothing, hairstyles, furniture, interiors, architecture as well as the cities in which they existed. This, combined with her extensive research, presents the reader with many insights into the relations between the two countries and their intertwined histories through the lives of these exceptional girls and their extraordinary adventures.

As Miriam Kingsberg of the Los Angeles Review of Books wrote, “Daughters… is, perhaps, less a story of Japanese out of place in their country, than of women ahead of their time.” Laky adds that while she was a professor of art and design at the University of California, Davis, she encouraged her students to study abroad. “This book illustrates how education and experience in a foreign country enhances understanding of other cultures and peoples – perhaps more important today than in the 1870s and 80s. I believe travel also greatly inspires creativity.”

It is a sad and exciting story about a typical lonely man in today’s Denmark, she wrote. “Written in a wonderful language – so one can just imagine him, by reading it and it is just as sad as Stoner.

As always, enjoy!