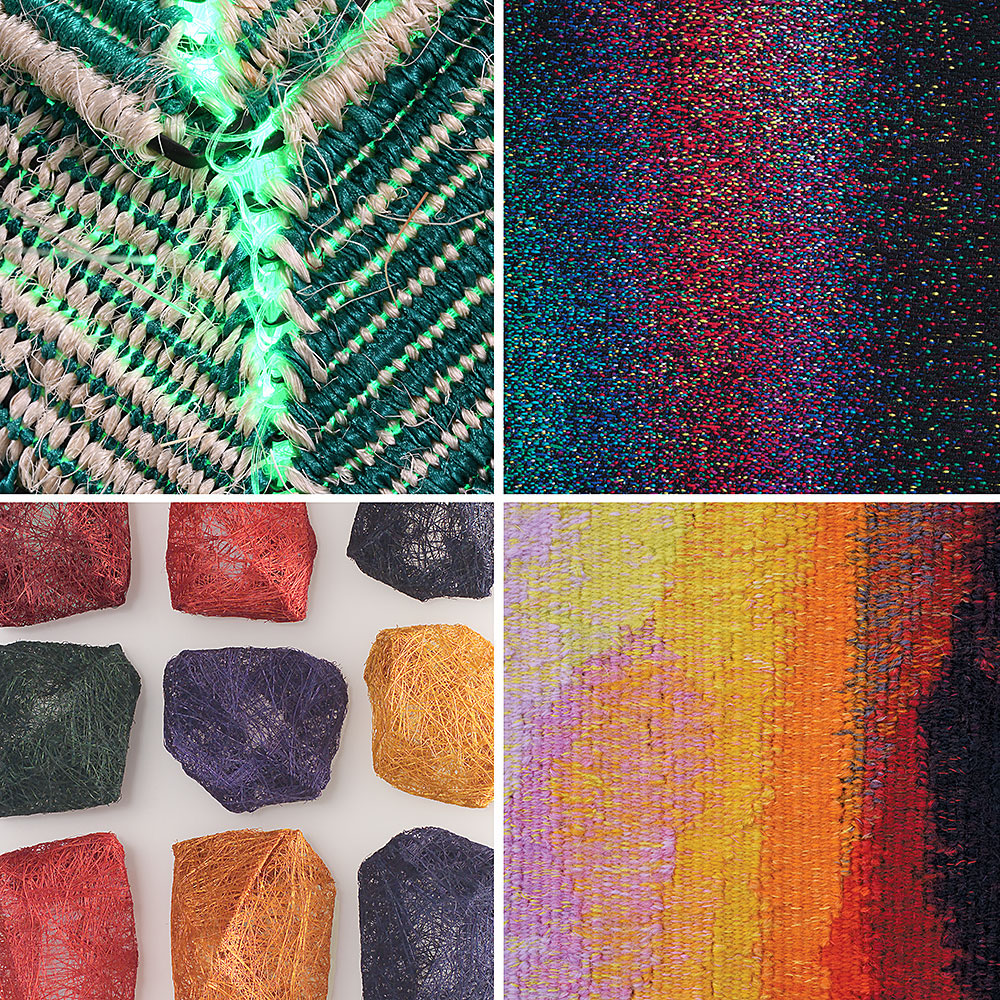

The Cordis Trust presents a special exhibition in conjunction with Visual Arts Scotland at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh. Over Under : Under Over explores weave in its widest context through the work of six contemporary artists: Elizabeth Ashdown, Celia Pym, Dail Behennah, Sue Lawty, Sarah Jane Henderson and Sadhvi Jawa.

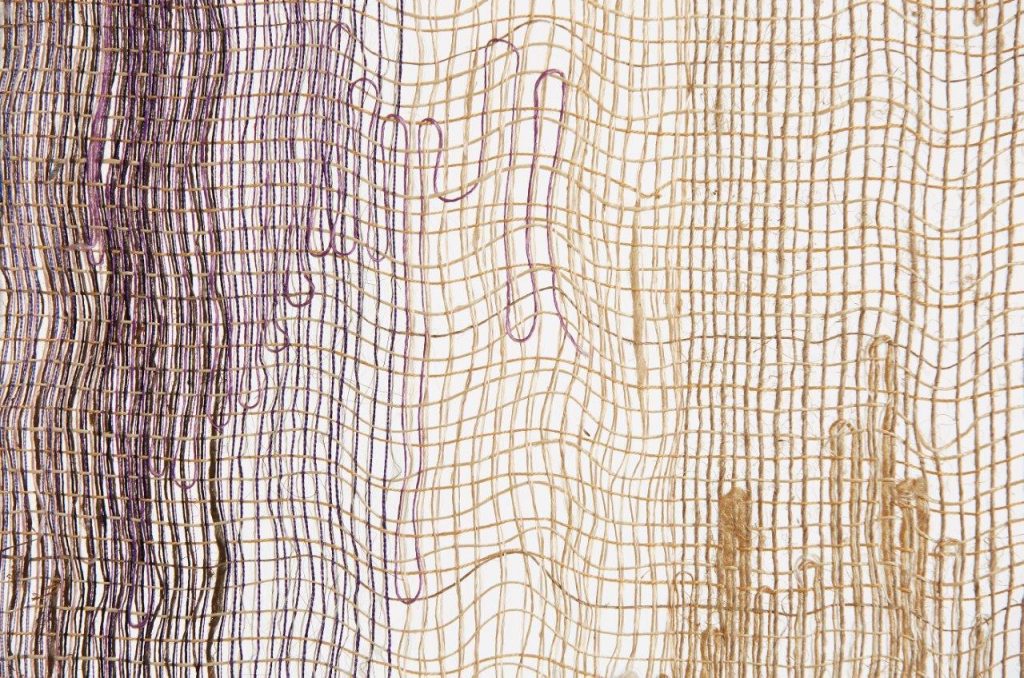

Cordis states: “Straying from their usual adherence to the traditional principles of woven Gobelin tapestry, this project aims to explore the wider applications of the woven form.” The artists were chosen because their work is constructed in a similar way to tapestry, or because they use techniques that resonate with the principles of weaving, whether that be through the interlacing of materials or of repetitive gesture.”

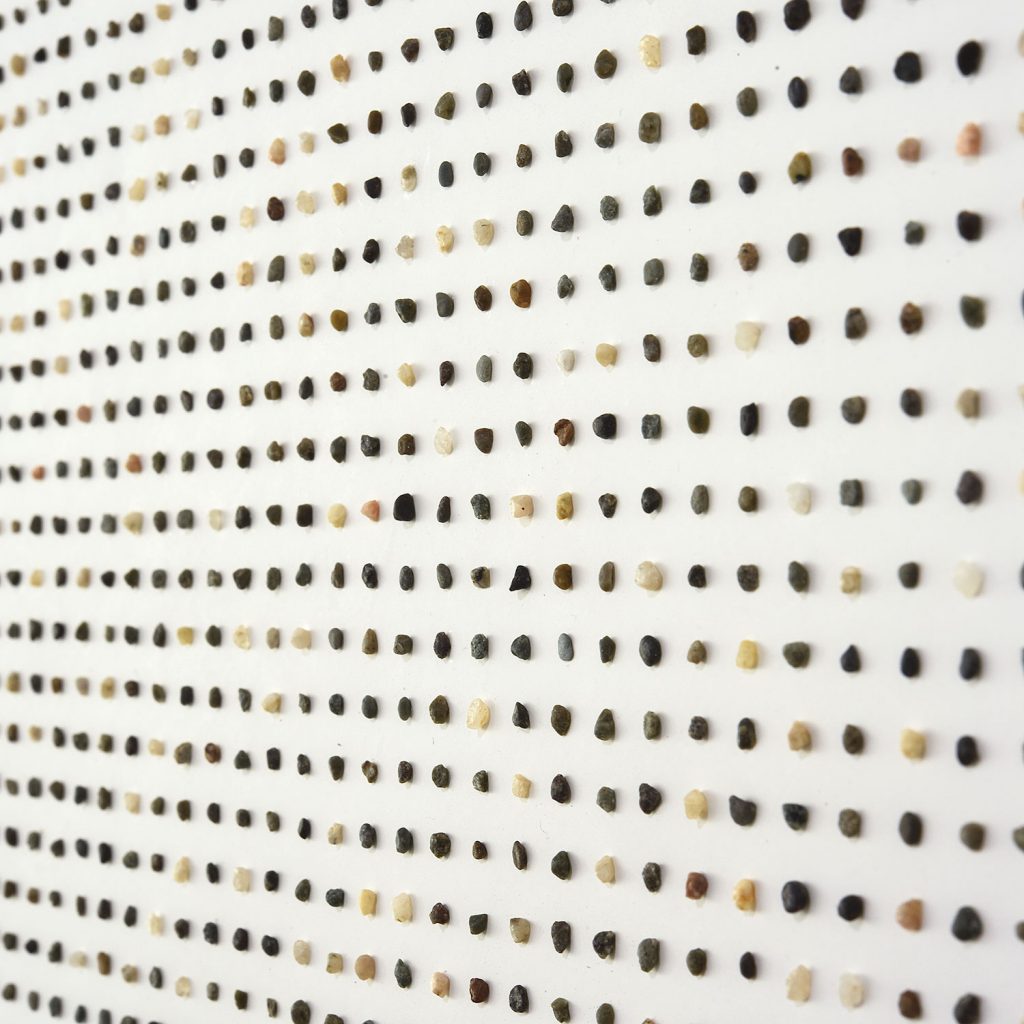

Sue Lawty’s work In this exhibition is made of found stones. She collects, organizes and orders thousands of tiny rock fragments to create a kind of pixilated cloth. Among Dail Behennah’s works in this exhibition are pieces paper, made with a three-dimensional, three-directional plaiting technique.

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, Upper Galleries through January 30th 2020.