War and violence are often influences for artistic works. In the last of our three columns on Art and Politics we look at three works in which artists have commented on specific conflicts and three that address the futility violence in differing contexts.

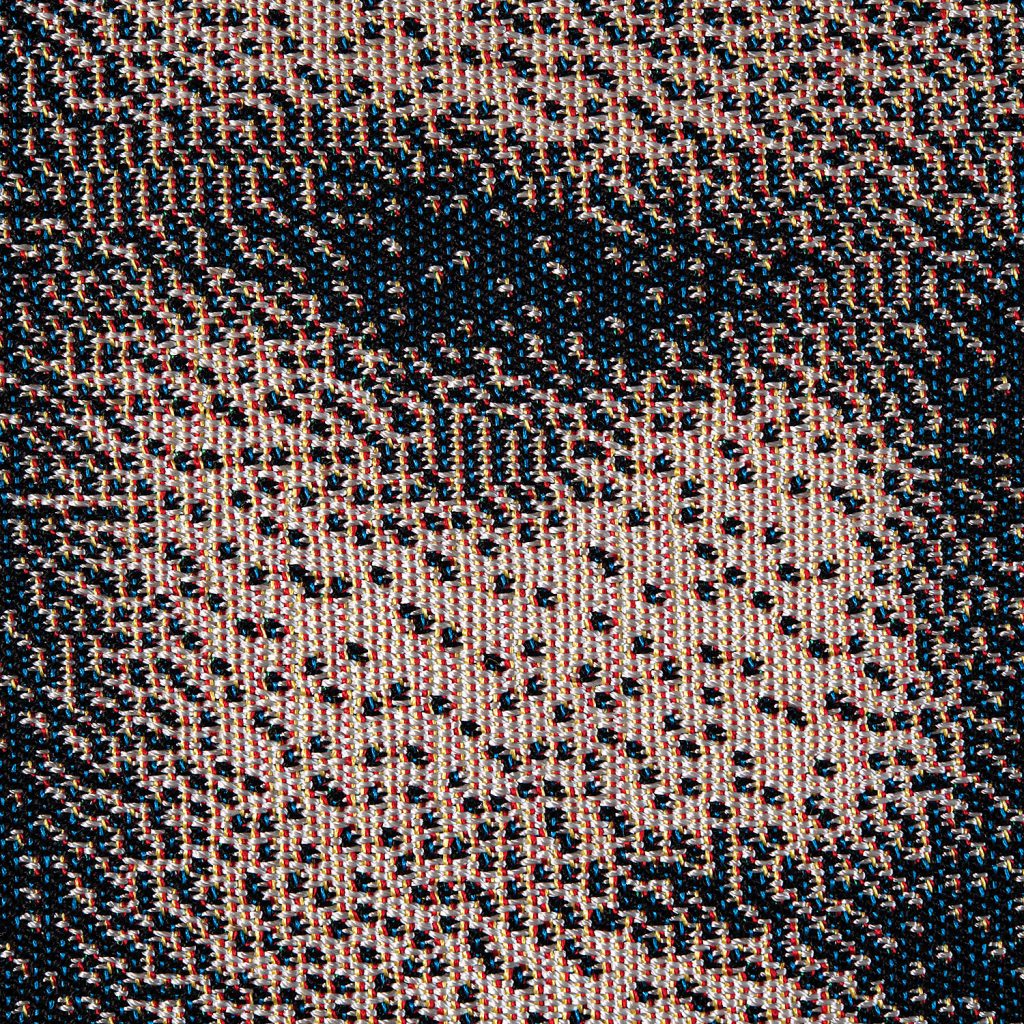

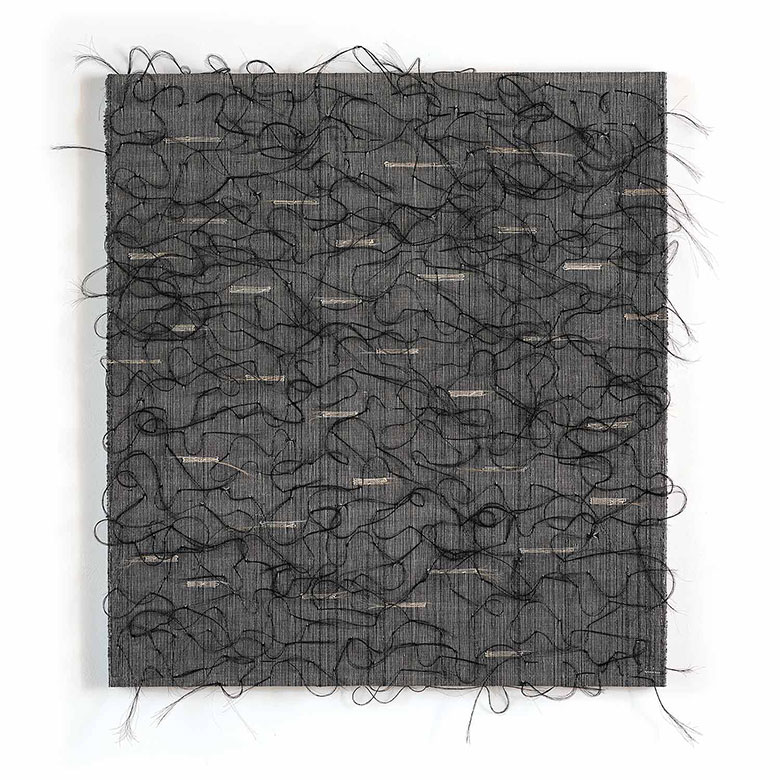

Concerns about war animate Compound, a work by Norma Minkowitz a large panel that chronicles a nightmare scenario, the last moments of Osama Bin Laden’s life. It features a tiny-mesh crocheted surface. It has a powerful push me/pull me effect once the subject matter– which includes stylized soldiers, SEALS parachuting from a helicopter, the compound where Bin Laden was hiding, and the World Trade Center — clarifies itself. This whole is an unforgettable image.

Responding to a call for art for a browngrotta arts’ exhibition entitled Stimulus: art and its inception in 2011, Norma Minkowitz began, as she usually does, to sketch. “I began in a spontaneous, unplanned manner,” Minkowitz explains, “arranging lines and subtle patterns, until I had a feeling of the direction it would take. Suddenly, I realized that the linear image had become the apparition of an aerial view of the compound where Osama Bin Laden was found, which I had seen in a newspaper article. Compound combines a replica of the space and my vision of the event.“

“This is not my usual way of working,” she says. It is more literal because of its historic significance. I enjoyed this different approach and found it quite timely as we remembered the attack on our country on September 11, 2001. I wanted to commemorate courage, justice and the resolve of the USA.”

The war in Iraq influenced Dona Anderson, as well and resulted in a series of “armor” pieces, including Women Warriors. Anderson’s granddaughter was in the army stationed in Japan while the granddaughter’s husband was in Iraq. When he came home for a break, he said he did not have any body armor. Anderson was so bothered by this information that she used her art to create some stylized armor for him.

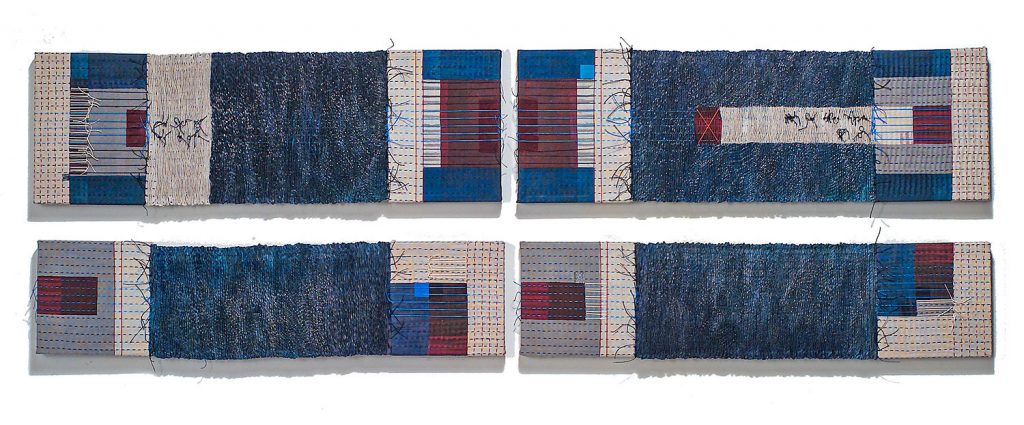

A previous conflict in Latin America led to the creation of a textile construction, El Salvador, by Ed Rossbach in 1984. Here, the artist using very simple materials constructed a powerful anti-war statement. The death squads in El Salvador killed many thousands of people before the civil war ended. Rossbach pushed the bounds of conventional 1950’s design. His art used raw materials — like camo mesh — to create forms that explore context, scale and juxtaposition to create irony

Gyongy Laky, a student of Rossbach’s, regularly addresses political issues in her work. Laky is a powerful advocate for the environment as well as a proponent of the hiring of more women at the University of California, Davis where the artist taught for many years. Through Globalization IV Collateral Damage, she speaks with great force and conviction about the utter waste of blood and treasure that is war. Constructed of ash and commercial wood scraps the three letters spell WAR but can also be rearranged to create other vivid elucidations of the subject: MAR, ARM, RAW, and RAM. Bullets for building and red paint are also used in the construction to dramatic effect.

In Help-Siring Soldiers to Sacrifice, Judy Mulford, has created a female figure with bullet casings making up her skirt to illustrate the tragedy for mothers in war zones, whose children are served up as fodder for never-ending conflicts. “My art honors and celebrates the family,” says the artist. “It is autobiographical, personal, graphic and narrative. Each piece I create becomes a container of conscious and unconscious thoughts and feelings, one that references my female ancestral beginnings.”

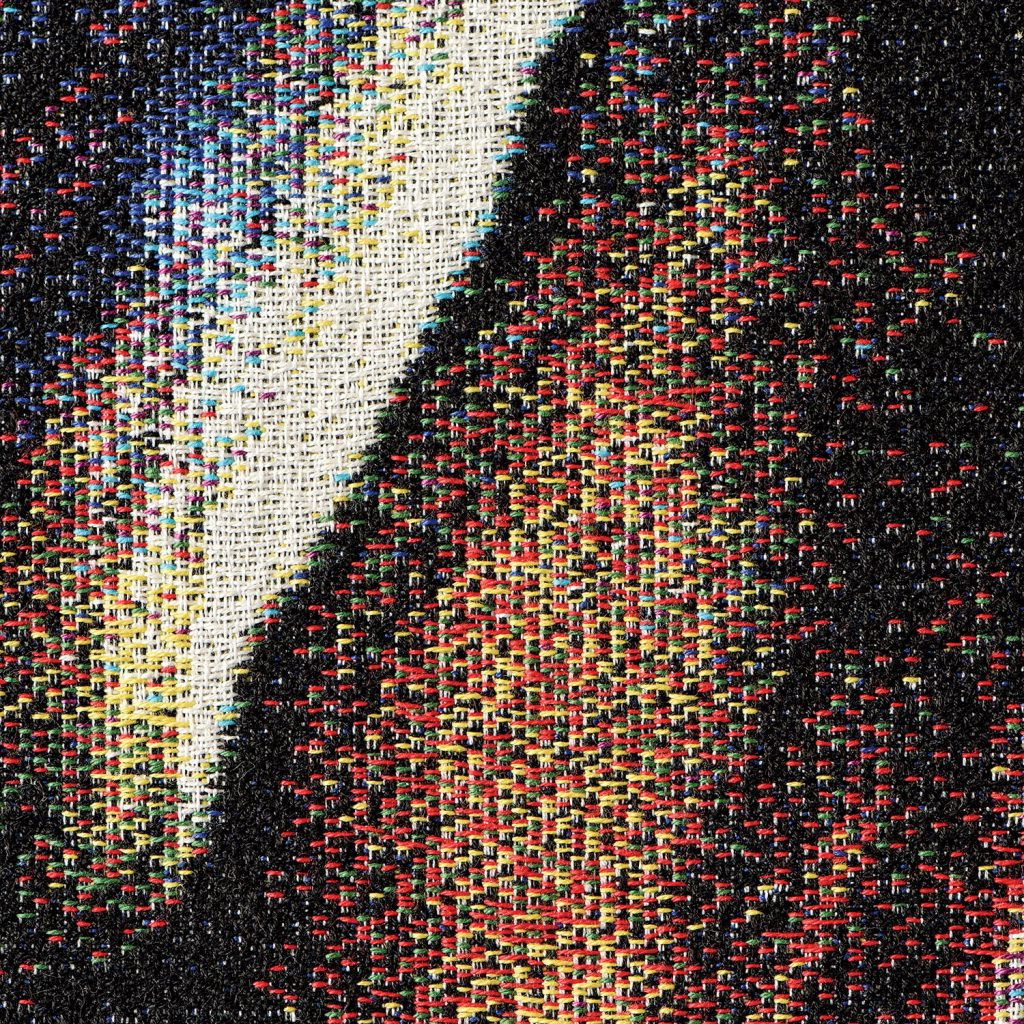

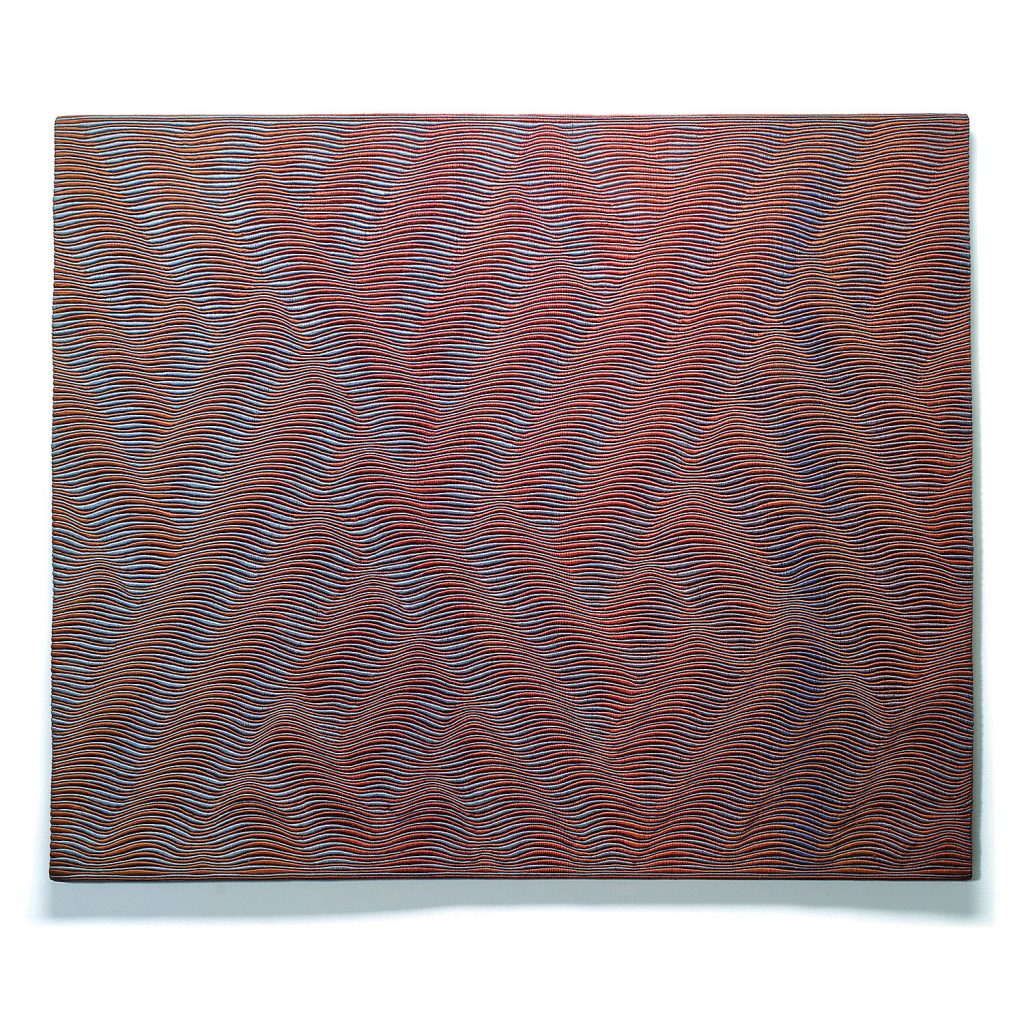

James Bassler commented on gun violence in schools in a series of vests that make up NRA Approved. “The cloth I wove, batik dyed and stitched, was inspired by the 19th Century Japanese fireman’s jacket,” he explains. “It was also inspired by our 21st Century public debate about gun violence and what we, as a nation, could do to make our schools safe from the tragic incidents of our times. The NRA has openly suggested that teachers and students wear bullet-proof vests. Often, our young students do wear waterproof aprons when doing creative work. Here, in these woven sculptural forms, I have added camouflage to help conceal children in harm’s way. Camouflage, indeed, has been used throughout.”

Artists can — and do — share their political observations through their work. The rest of us can do the same through our votes. Please do!