This Spring in Connecticut brings an abundance of daffodils and in the US and abroad a slew of art exhibitions. From Scotland to San Francisco to Seoul, we’ve rounded up some suggestions for you:

Jane Balsgaard

April 6 – May 5, 2024

Vejle Kunstforening

Søndermarksvaj 1

Vejle, Denmark 7100

https://www.vejlekunstforeningmoellen.dk/

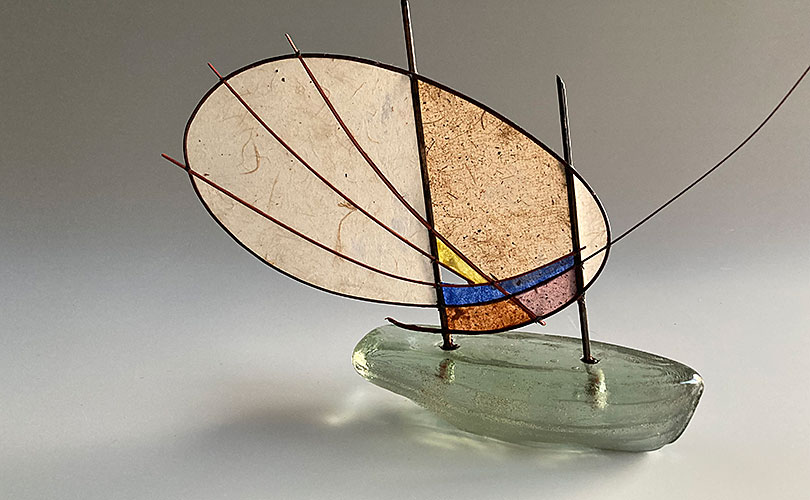

This exhibition of Jane Balsgaard’s art work of glass twigs and plant paper will open in Velje, Denmark this April.

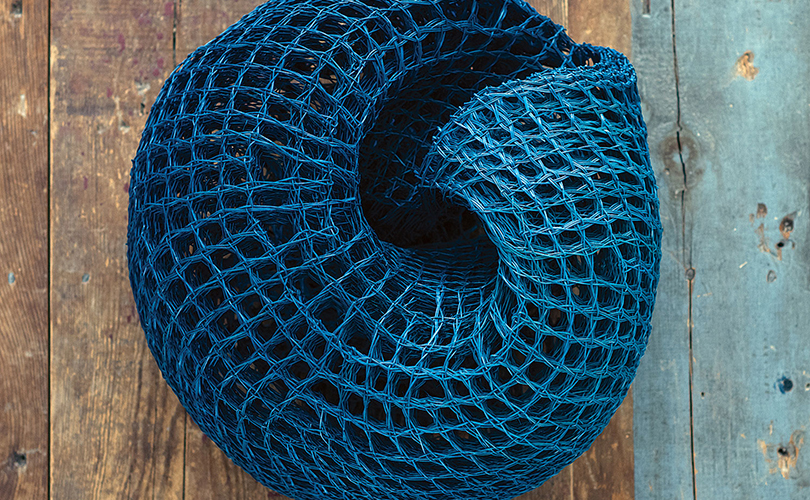

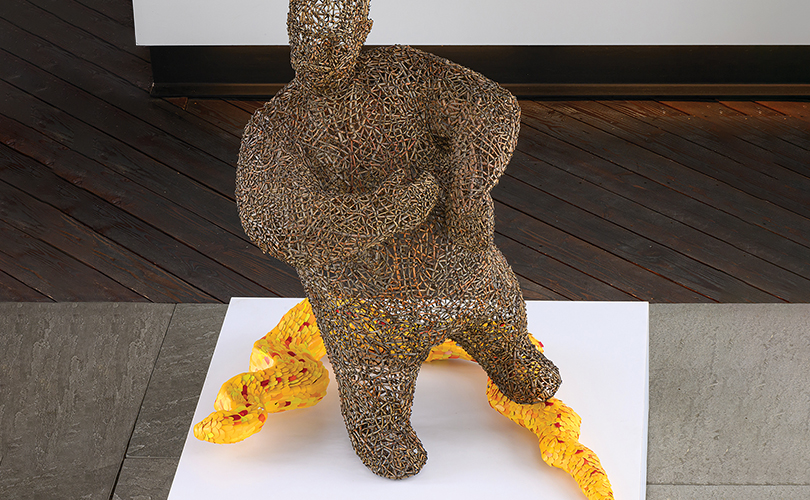

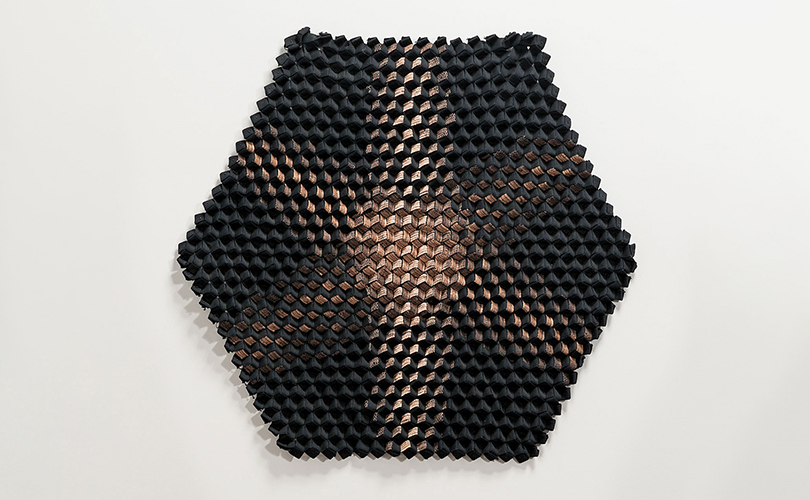

Four Stories of Swedish Textile: Inger Bergstöm, Jin Sook So, Katka Beckham Ojala, Takao Momijama

March 20 – April 2, 2024

Suaenyo 339,

339 Pyeongchang-gil, Jongno-gu

Seoul, Korea

http://sueno339.com/?ckattempt=1

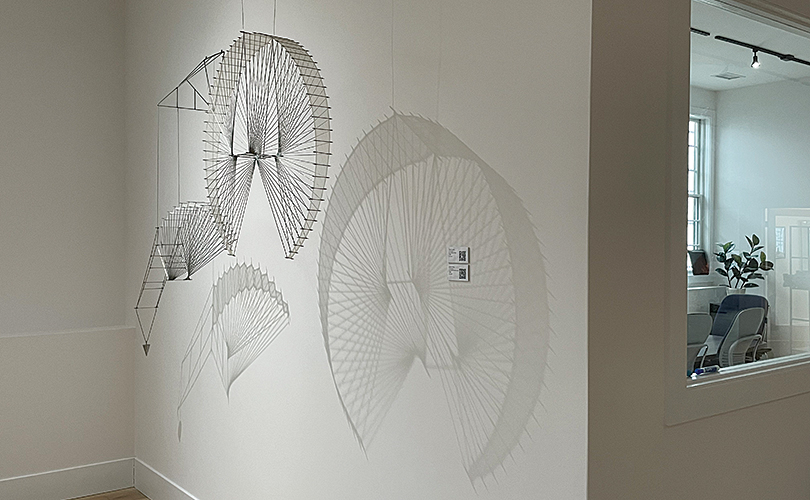

This is an exhibition of four very different art practices, including work in stainless steel mesh by Jin-Sook So. “Using textiles as an artistic medium opens up a world of possibilities, interpretations and expectations,” write the exhibition’s curators. “How the individual artist works in this realm is unpredictable and can lead to totally different genres and contexts. The exhibition, 4T – Four Swedish Stories of Textile, shows the works of a group of artists who despite their different expressions are united by an interest specifically for textile surfaces.”

Andy Warhol: The Textiles

Through May 18, 2024

Dovecot Studios

10 Infirmary Street

Edinburgh, SCOTLAND EH1 1LT

https://dovecotstudios.com/whats-on/andy-warhol-the-textiles

Andy Warhol: The Textiles takes viewers on a journey through the unknown and unrecorded world of designs by the influential artist before his Silver Factory days. As the originators explain, by showcasing over 35 of Warhol’s textile patterns from the period, depicting an array of colorful objects; ice cream sundaes, delicious toffee apples, colorful buttons, cut lemons, pretzels, and jumping clowns, this exhibition demonstrates how textile and fashion design was a crucial stage in Warhol becoming one of the most iconic artists of the 20th century. A book accompanies the exhibition: Warhol: The Textiles.

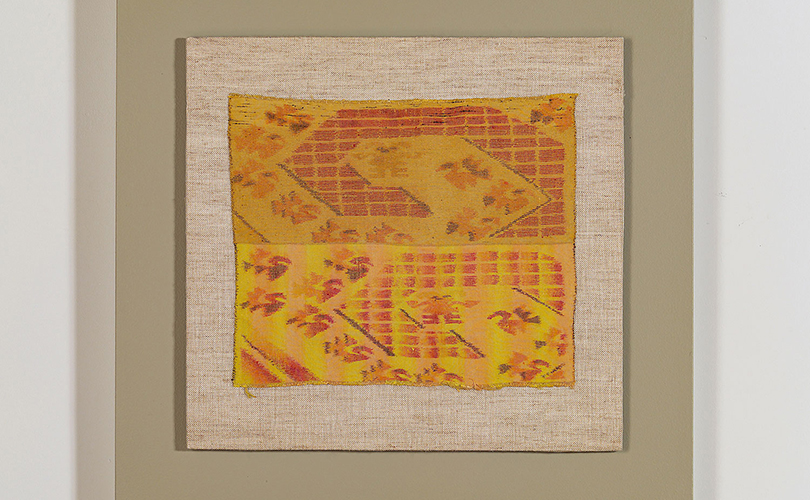

Irresistible: The Global Patterns of Ikat

Through June 1, 2024

George Washington University and Textile Museum

701 21st St. NW

Washington, DC 20052

museuminfo@gwu.edu

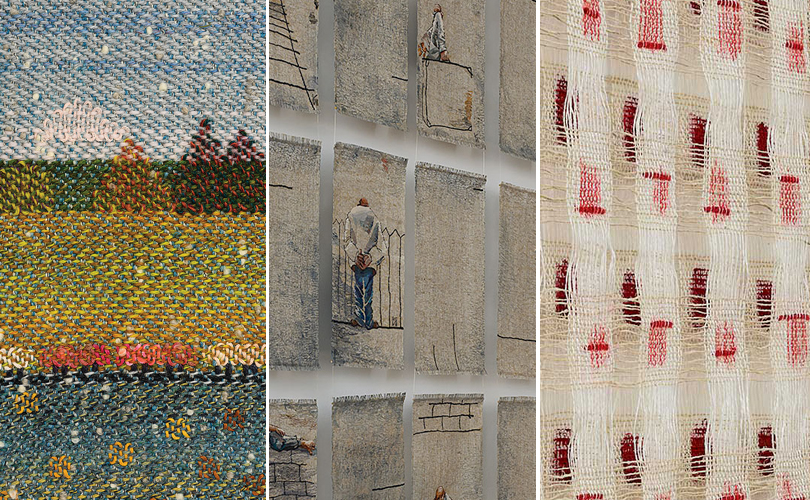

Prized worldwide for producing vivid patterns and colors, the ancient resist-dyeing technique of ikat developed independently in communities across Asia, Africa and the Americas, where it continues to inspire artists and designers today. This exhibition explores the global phenomenon of ikat textiles through more than 70 masterful examples — ancient and contemporary — from countries as diverse as Japan, Indonesia, India, Uzbekistan, Côte d’Ivoire and Guatemala. Included are works by Polly Barton, Isabel Toledo, and Ed Rossbach.

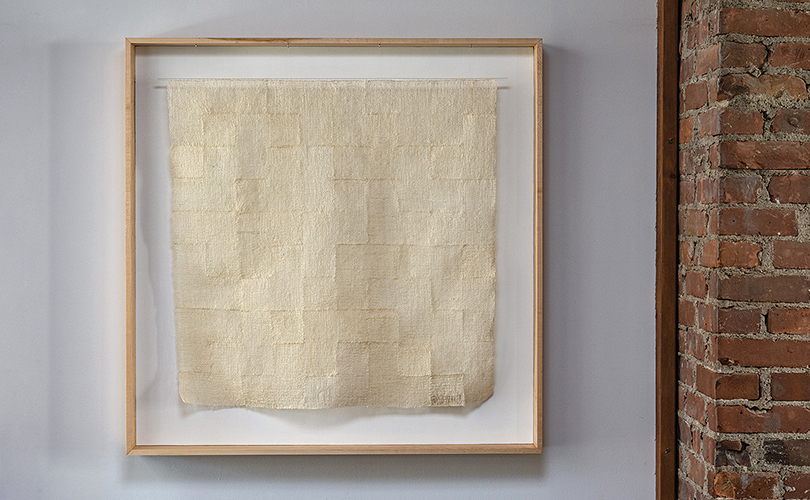

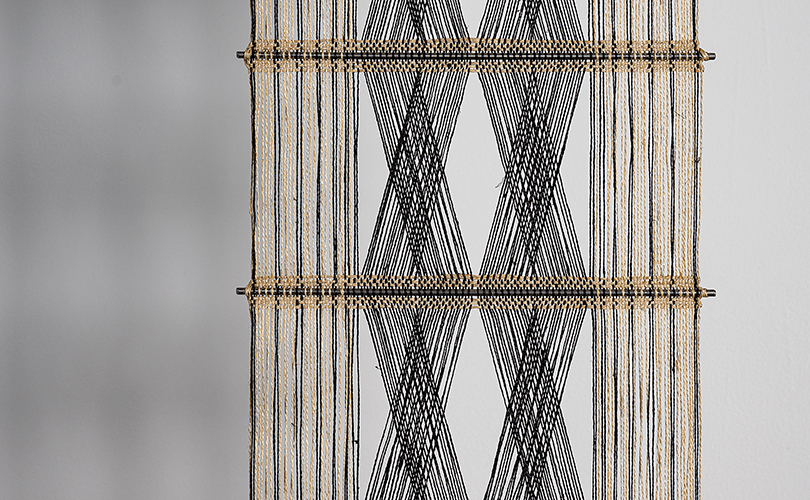

Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art

Through June 16, 2024

Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028

https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/weaving-abstraction-in-ancient-and-modern-art

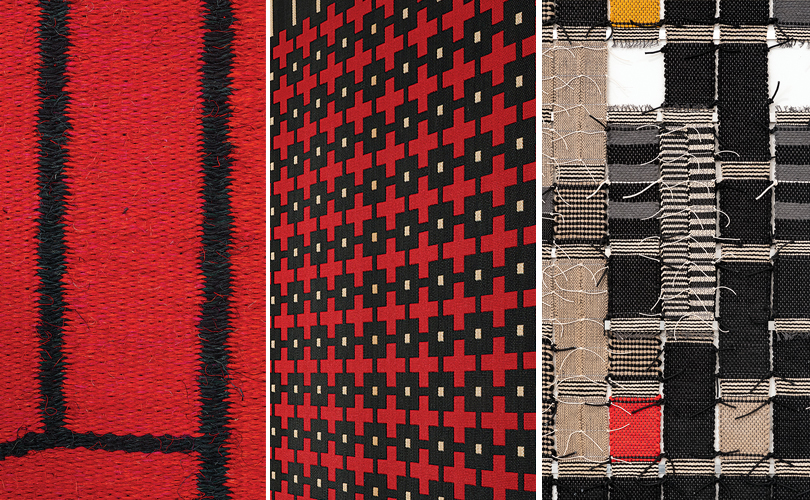

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Hyla Skopitz

The process of creating textiles has long been a springboard for artistic invention. In Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art, two extraordinary bodies of work separated by at least 500 years are brought together to explore the striking connections between artists of the ancient Andes and those of the 20th century. The exhibition displays textiles by four distinguished modern practitioners—Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Lenore Tawney, and Olga de Amaral—alongside pieces by Andean artists from the first millennium BCE to the 16th century.

On and Off the Loom: Kay Sekimachi and 20th Century Fiber Art

Lecture and Video with Melissa Leventon and Ellin Klor

April 20. 2024

1 p.m. EDT

de Young Museum

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive

Golden Gate Park

San Francisco, CA 94118

https://www.textileartscouncil.org/post/on-and-off-the-loom-kay-sekimachi-and-20th-century-fiber-art

Kay Sekimachi is esteemed as an innovator in contemporary fiber art. Her vision has had an impact on many outstanding artists. Sekimachi came of age at a boom time for fiber art, when many artists were experimenting with dimensional weaving both on and off the loom and were challenging old art world hierarchies in the process. In this talk in person and on Zoom, Melissa Leventon will discuss Sekimachi’s oeuvre within the wider context of fiber art in the 20th century.

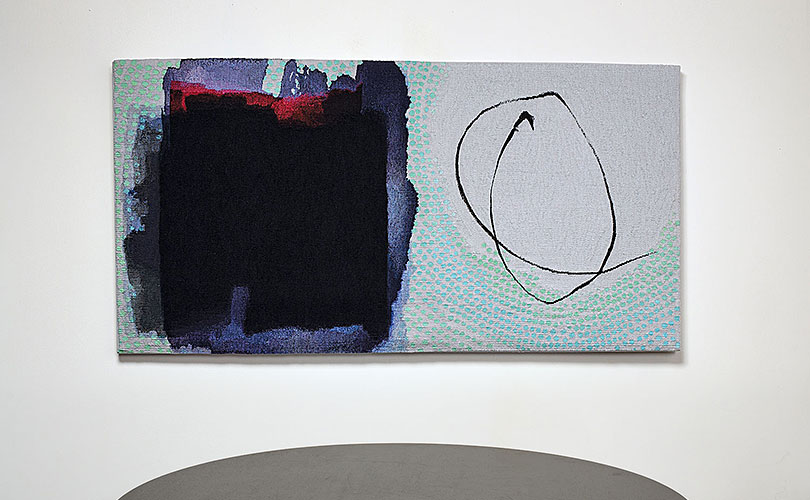

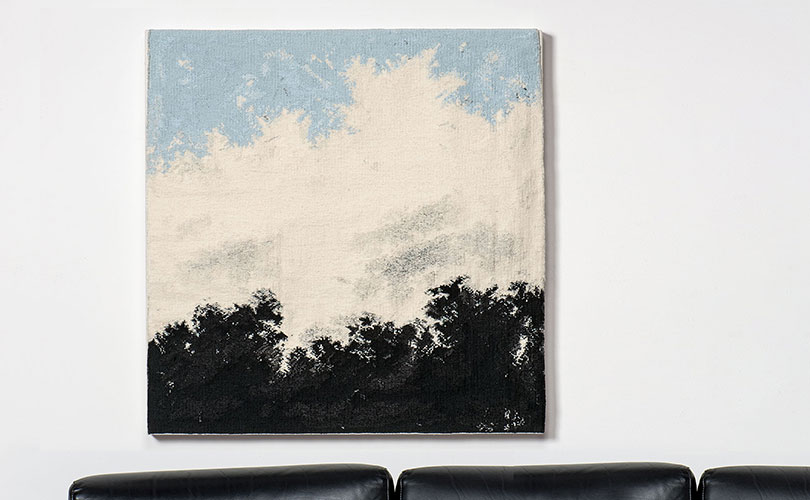

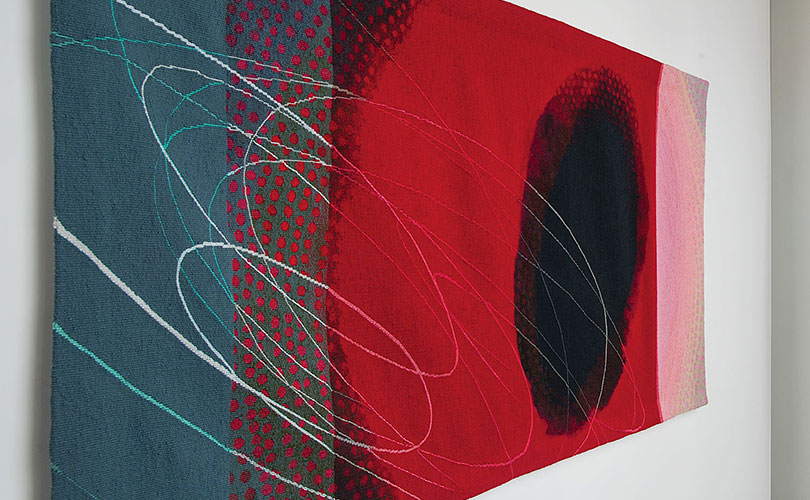

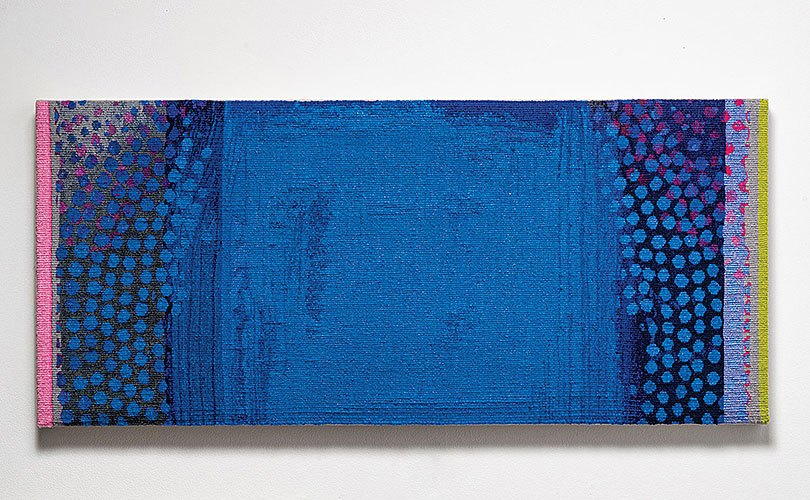

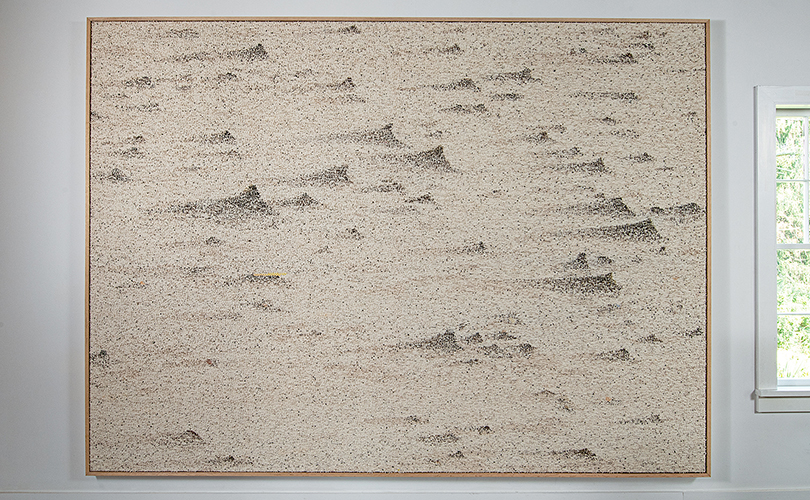

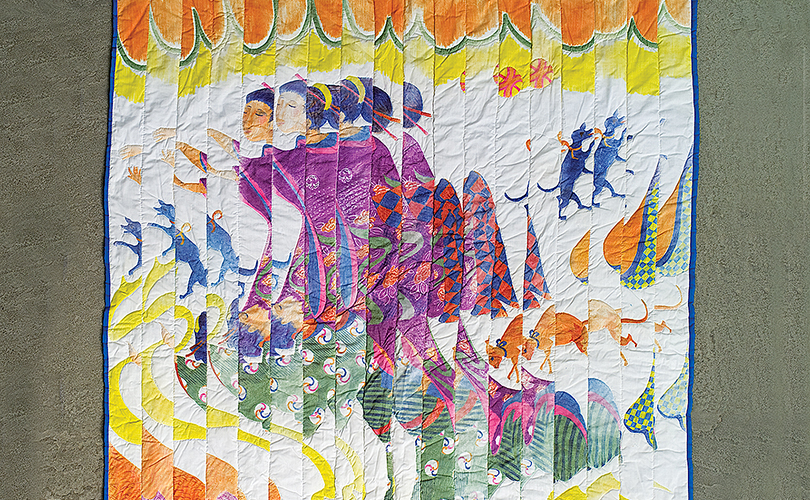

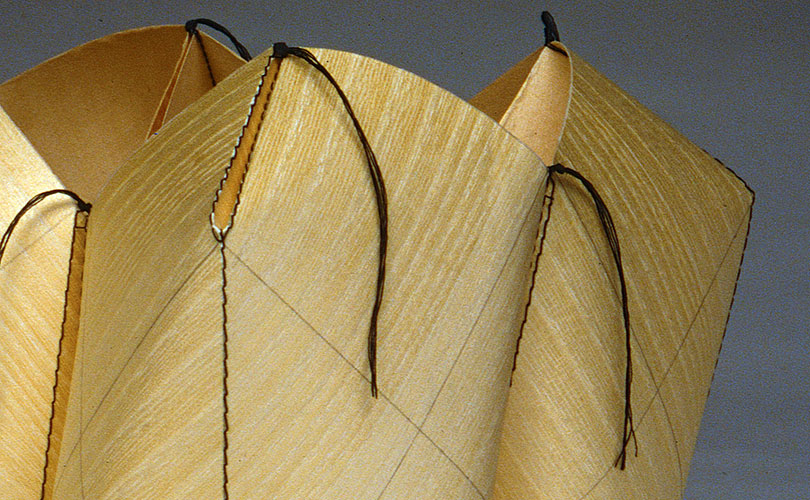

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction

Through July 28, 2024

National Art Gallery

East Building, Concourse Galleries

4th Street and Constitution Avenue, NW

Washington, DC

https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2024/woven-histories-textiles-modern-abstraction.html

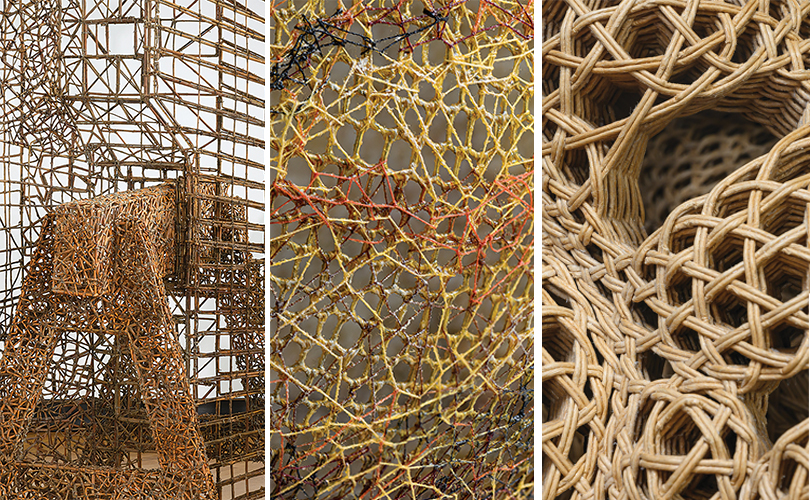

This transformative exhibition has moved from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to the National Gallery in DC. It explores how abstract art and woven textiles have intertwined over the past hundred years.This transformative exhibition explores how abstract art and woven textiles have intertwined over the past hundred years. In the 20th century, textiles have often been considered lesser—as applied art, women’s work, or domestic craft. Woven Histories challenges the hierarchies that often separate textiles from fine arts. Putting into dialogue some 160 works by more than 50 creators from across generations and continents, including Katherine Westphal, Dorothy Gill Barnes, and Ed Rossbach, this exhibition explores the contributions of weaving and related techniques to abstraction, modernism’s preeminent art form. The book that accompanies the exhibition, Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, can be found on our website.