ABROAD

Ctrl/Shift – Sleaford, United Kingdom

Across the pond, Ctrl/Shift: New Directions in Textile Art is currently on show at the National Centre for Craft & Design. Ctrl/Shift, which features work by browngrotta arts artist Caroline Bartlett, presents a wide variety of pieces which present how artists transform their pieces through their creative processes. Focusing on shifts, changes

El Anatsui: Material Wonder – London, United Kingdom

El Anatsui’s work is on view at October Gallery in London through the end of April. The exhibition, El Anatsui: Material Wonder, coincides with the largest retrospective of Anatsui’s work, El Anatsui: Triumphant Scale, at Haus der Kunst, Munich. Throughout his influential career, Anatsui has experimented with a variety of mediums, including cement, ceramics, tropical hardwood corrugated iron, and bottle-top, to name a few. October Gallery’s exhibition includes a variety of metal wall sculptures accompanied by a series of prints made in collaboration with Factum Arte. Want to see these one-of-a-kind pieces? Head over to October Gallery’s website HERE for visiting information.

Rehearsal, El Anatsui, Aluminum and copper wire, 406 x 465 cm, 2015. Photo Jonathan Greet/October Gallery.

A Considered Place – Drumoak, Scotland

A Considered Place, an upcoming exhibition at Drum Castle in Drumoak, Scotland, will share the work of browngrotta arts artists Jo Barker and Sara Brennan, along with Susan Mowatt, Andrea Walsh

In Paris, Jiro Yonezawa is among artists featured in

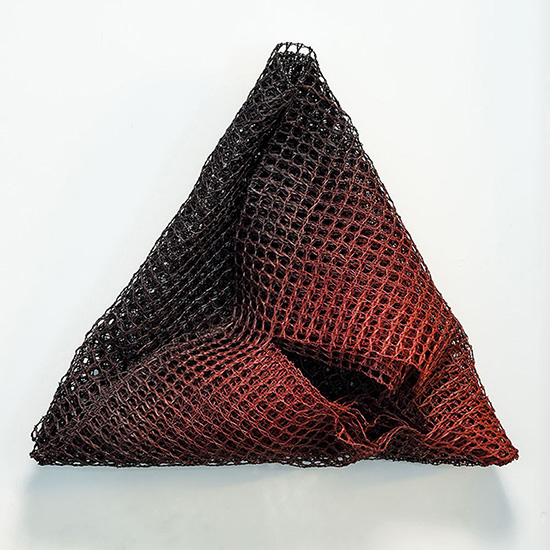

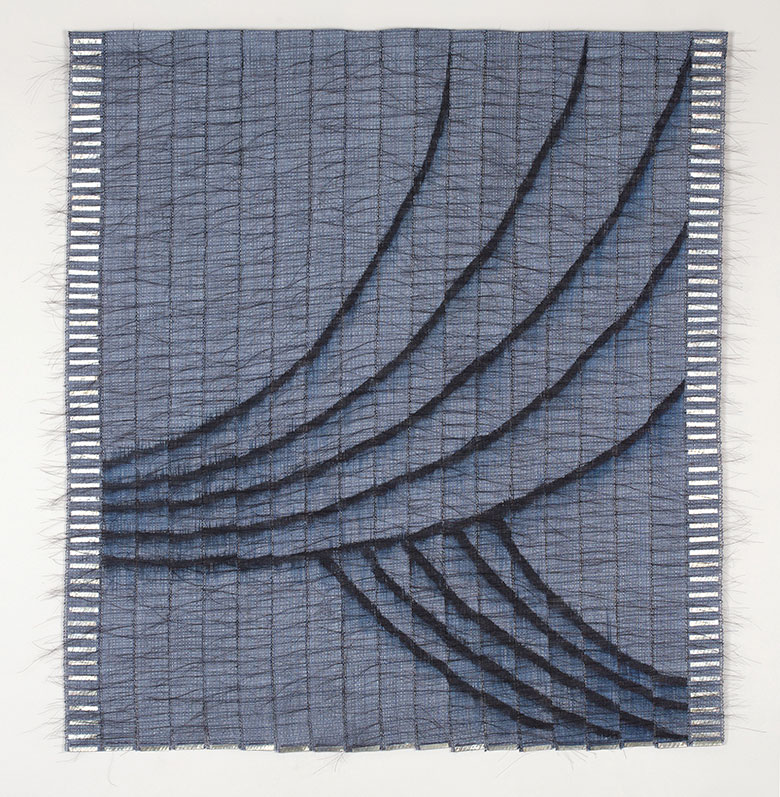

Certainty / Entropy (Peranakan 2), Aiko Tezuka, h27 x w76 x b71.5 cm, 2014. Loan:

Aiko Tezuka/Galerie Michael Janssen. Photo:

Edward Hendricks

Cultural Threads – Tilburg, Netherlands

If you happen to be in the Netherlands in upcoming months make sure to check out Cultural Threads at the Textiel Museum in Tilburg. Featuring work by Eylem Aladogan, Célio Braga, Hana Miletić, Otobong Nkanga, Mary Sibande, Fiona Tan, Jennifer Tee, Aiko Tezuka and Vincent Vulsma, the exhibition focuses on textiles as a tool for socio-political reflection. “We live in a world where boundaries between countries and people are becoming increasingly blurred, power relations are shifting radically and cultures are mixing,” states the Textiel Museum. As a medium, the unique qualities of textiles provide artists with a plethora of ways to communicate and explore identity in a globalizing world. Find more information on the Cultural Threads HERE.

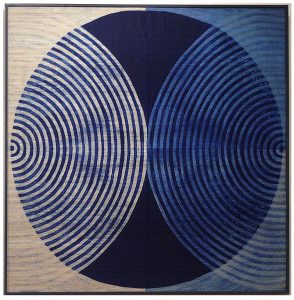

Artapestry V – Arad, Romania

Gudrun Pagter’s work in Artapestry V is

UNITED STATES

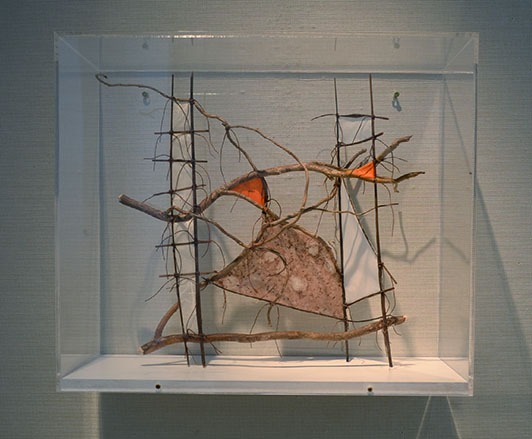

The Art of Defiance: Radical Materials – New York, NY

The current Michael Rosenfeld Gallery exhibition, The art of Defiance: Radical Materials, examines how artists such as Barbara Chase-Riboud, Betye Saar, Hannelore Baron, Nancy Grossman have utilized unique, groundbreaking materials in their work. For the exhibition, each artist utilized materials defined by their physicality, “representing a freedom from the constraints of traditional, male-dominated media in art history.” Each artists’ work blurred the traditional boundaries between two and three-dimensional design, which in turn has expanded the traditional categorical defines of art-making. In New York and want to check out the exhibition, visit the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery website HERE.

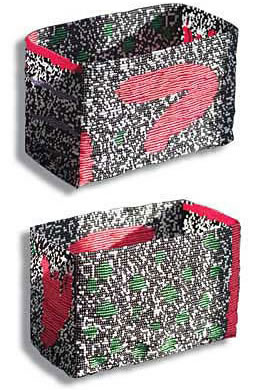

Digital jacquard,

The Empathy of Patience – San Luis Obispo, CA

International TECHstyle Art Biennial IV – San Jose, CA

Three hours