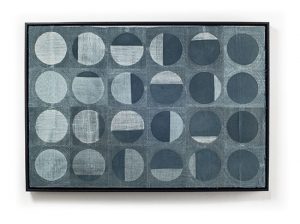

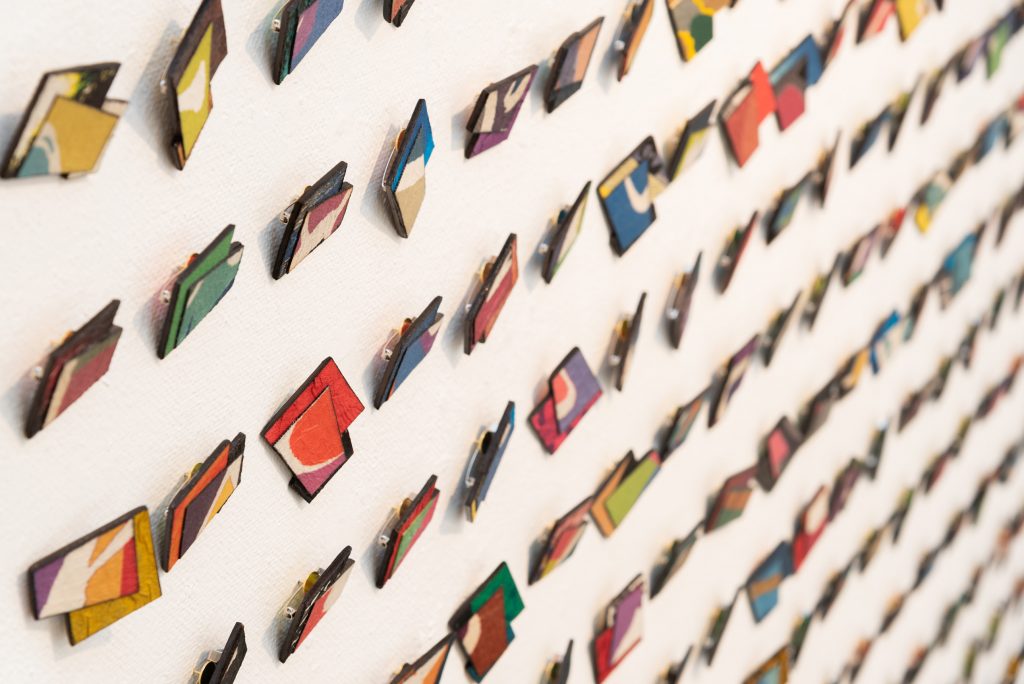

Installation by Hideho Tanaka. Photo by Hideho Tanaka.

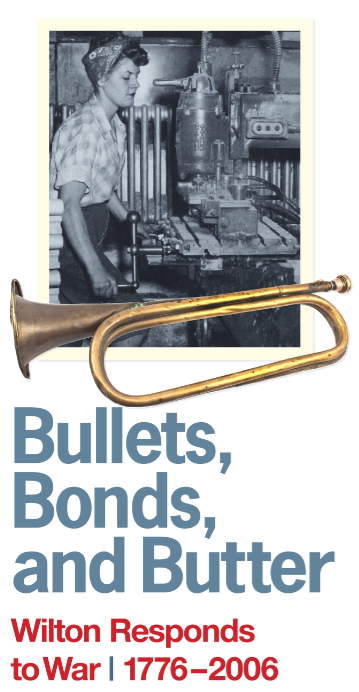

If you are in Miami, Los Angeles or Honolulu this summer be sure to visit these three not-to-be-missed exhibitions (and enjoy images from Hideho Tanaka’s recent solo show in Japan).

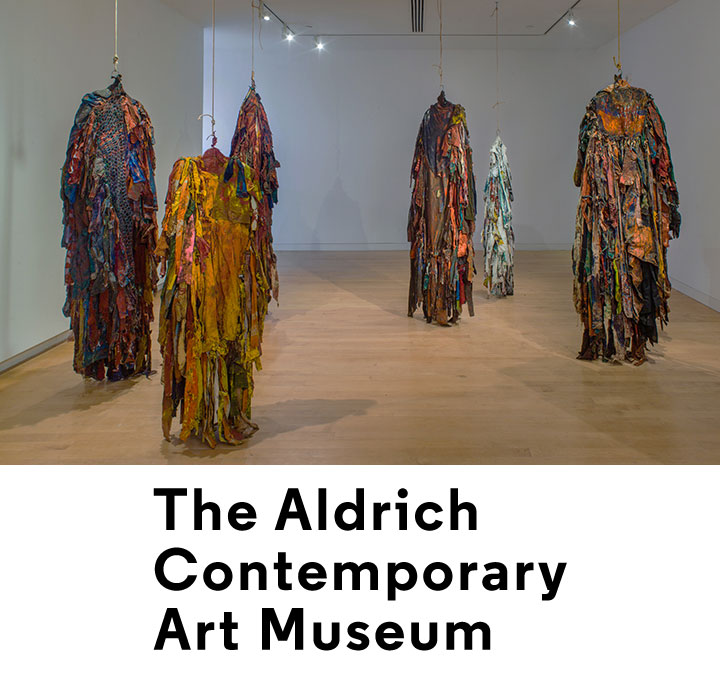

Sheila Hicks: Campo Abierto (Open Field)

April 13, 2019 -September 29, 2019

The Bass Museum of Art

2100 Collins Avenue

Miami Beach, FL 33139

305. 673.7530

Grouping works of art from various periods, Campo Abierto (Open Field) explores the formal, social and environmental aspects of landscape that have been present, yet rarely examined, throughout Sheila Hicks’ expansive career.

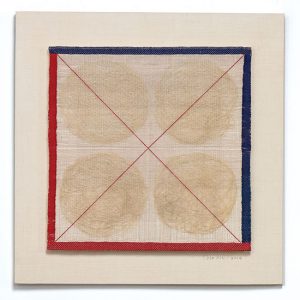

Fissures III, 2019

Karyl Sisson

vintage paper drinking straws, thread and polymer

framed 16.5″ x 16.5″ x 1.75″

Photo by Susan Einstein

Karyl Sisson: Fissures & Connections

May 11, 2019 –July 6, 2019

Craft in America Gallery

8415 W. Third Street

Los Angeles, CA, 90048M

323.951.0610

Los Angeles-based artist Karyl Sisson has a solo exhibition at the Craft in America gallery. The materials of everyday life, both past and present, are the fibers that Sisson weaves together to form sculptural and textured forms. Sisson draws inspiration from sources as diverse as Los Angeles’ landscape, microbiology, and fashion manufacturing. Glimpsing back at her work over three decades, pattern, repetition, and structure are unifying and focal themes that she explores dimensionally from her foundation in basketry and needlework. In her choice of reinventing undervalued materials, Sisson manages to confront domesticity and traditional gender roles. Her recent work with paper straws draws inspiration from cells and organisms, which inform the objects as she composes them and they grow seemingly naturally.

After studying painting and drawing at NYU, Sisson moved to Los Angeles and entered graduate school in 1983 at UCLA where she studied with Bernard Kester, one of the pioneering voices in the establishment of fiber as an art medium in the 1960s and 1970s. Ed Rossbach, Judy Chicago, Miriam Shapiro, Esther Parkhurst, and Neda al Hilali are among the artists who inspired her work and exploration of fiber early on.

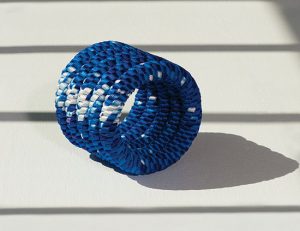

(right) Sampler VII- 1997-1998 Marian Bijlenga (Dutch, 1954) Horsehair, fabric, stitched

Constellation—drawing in space by Marian Bijlenga

May 18, 2019 – August 04, 2019

Honolulu Museum of Art

900 South Beretania Street

Honolulu, Hawaii 96814

808-532-8700

Marian Bijlenga, a Dutch contemporary artist, approaches mark-making with an innovative use of materials as a drawn “line.” Her unique constructions respond to the environment, echoing her interpretations of interconnected webs of fiber. Drawing on a non-traditional use of the sewing machine, these sculptures are mere whispers of dark and light, playing on positive and negative spaces, sometimes barely visible gestures as a shadowy effect.

Hideho Tanaka Sole Exhibition 2019, Emerging

May 25, 2019-May 3

Hideho Tanaka also had a one-person exhibition last month in Japan, Hideho Tanaka Sole Exhibition 2019, Emerging While he was engaged in education and research at Musashino Art University, in the Craft and Industrial Design Department for many years he usedfiber to pursue three-dimensional modeling expressionA novelist of a writer who was also a fiber artist, wrote monyaart: http://monyaart.jugem.jp/?eid=3778. The small works on the wall were organized in a grid. “I am overwhelmed by a large amount of ‘brooches,'” Monyaart quoted the artist. These are designs of two or three rectangles on which a hand-drawn image is superimposed. The exhibition also featured larger works were also displayed.