New Date: September 12 to 20, 2020: Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber for Three Decades

Optimistic as we are about June — when we’d tentatively rescheduled our Spring exhibition — as being the time when we’ll have passed the illness apex and be able to go out and about once more, we’ve decided a new date in September makes more sense. We’re afraid that masks and gloves and disinfectant will still be de rigeur in June and they will impact viewers experience of the art. Air travel restrictions may still be be in place, which means fewer artists in attendance and and fewer out-of-town visitors.

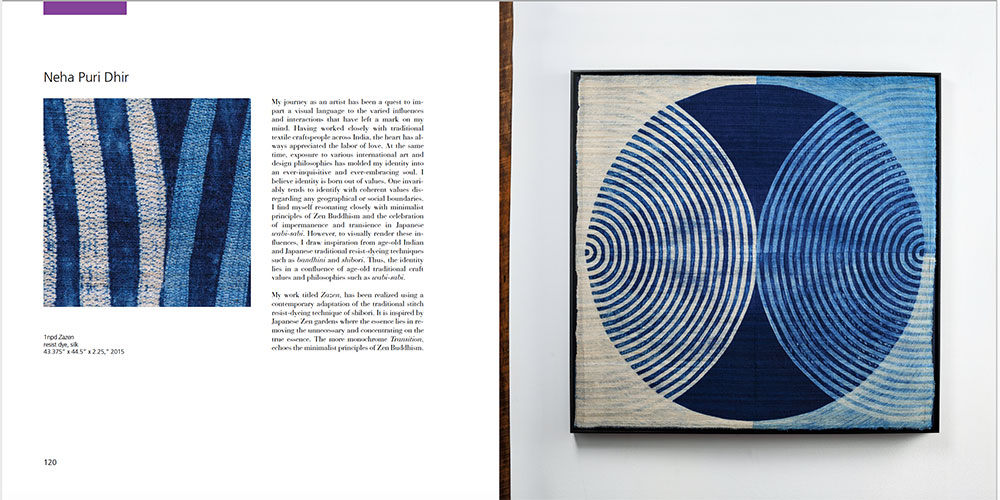

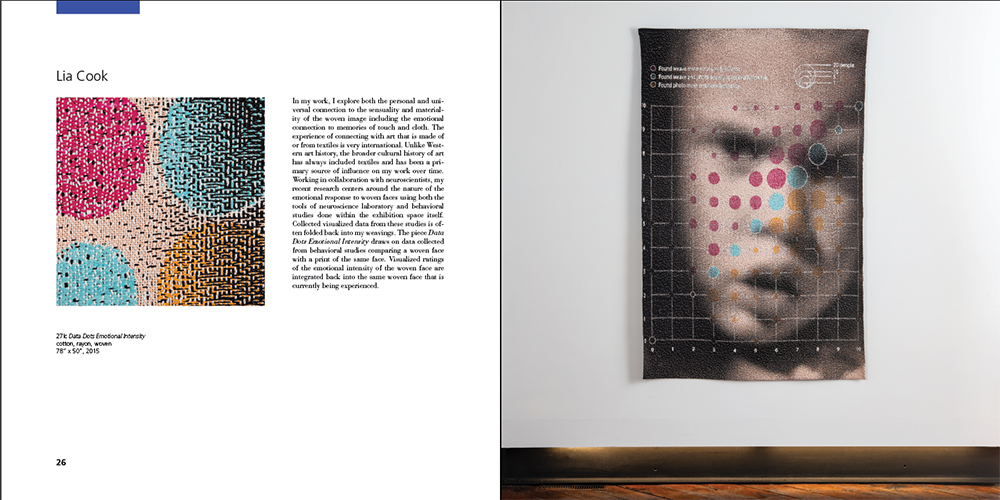

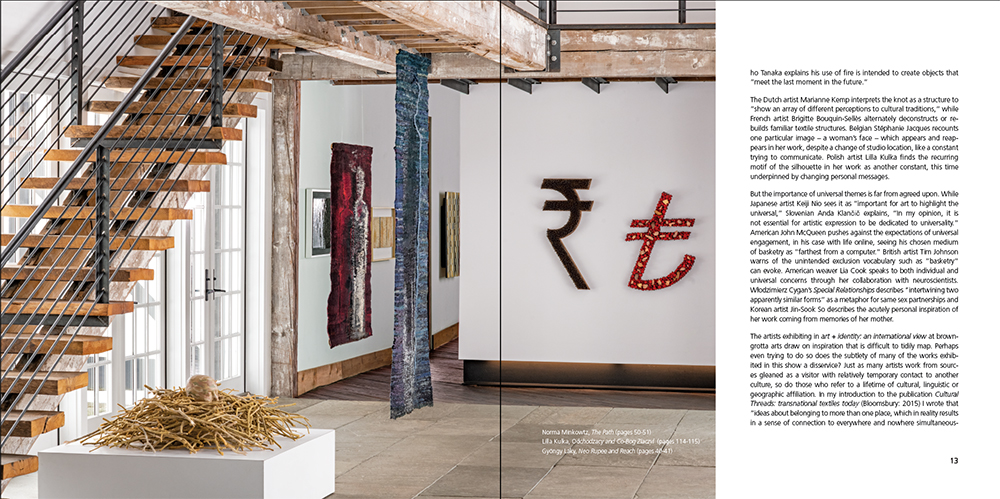

An exciting exhibition: Both impacts would be unfair as Volume 50: Chronicling Fiber for Three Decades has shaped up to be an exciting show. It features significant works by Lia Cook, Gyöngy Laky, Aleksandra Stoyanov and Grethe Sørenson. Works by well-known but new-to-the-gallery artist, James Bassler, are included in addition to striking installations by Annette Bellamy and Agneta Hobin and new approaches by Tim Johnson, Kari Lønning, Carolina Yrarrazával and Dail Behennah. Strong works by Chiyoko Tanaka, Neha Puri Dhir and Adela Akers are among other offerings from the more than 60 artists participating.

So, in 2020, our Spring show will become a Fall show. The Artist Reception and Opening will be onSaturday, September 12th. We’ll welcome you all then with whatever precautions are appropriate.

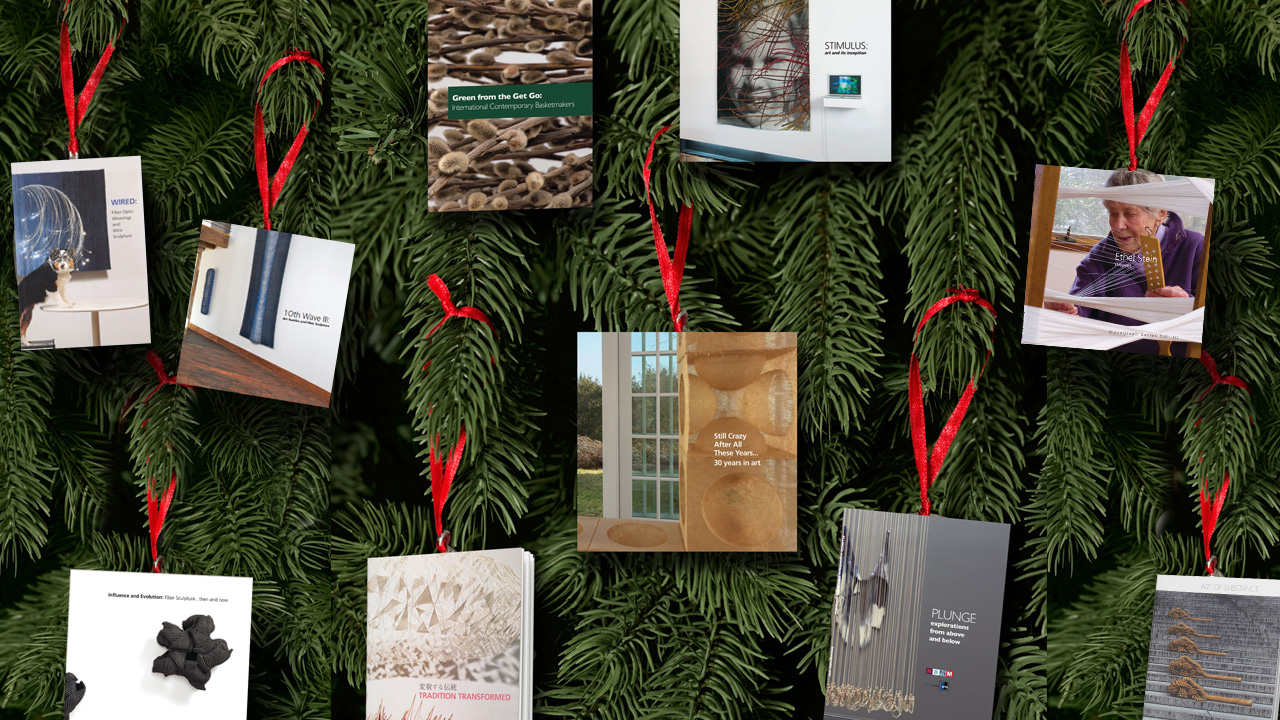

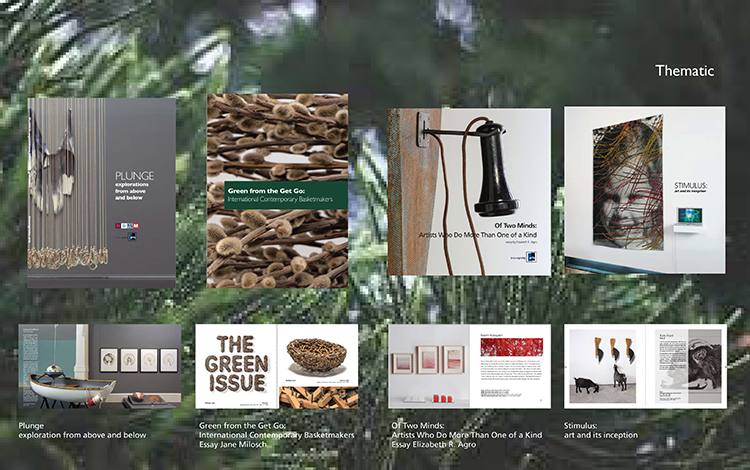

In the meantime, online: As a run up to September, we’ll be presenting a series of online exhibitions on Artsy highlighting artists and catalogs from our archives:

May 11th: Catalog Look back: California Dreaming Vols. 26, 20, 6 and more

June 8th: Catalog Look back: Cross Currents – Arts Influenced by Rivers and the Sea Vols. 38, 35 and more

July 13th: Catalog Look back: Fan Favorites — Sekimachi, Sekijima, Laky and Merkel-Hess,Vols. 24, 19, 2, 3, 8, 5, 15, 16, 19 and more

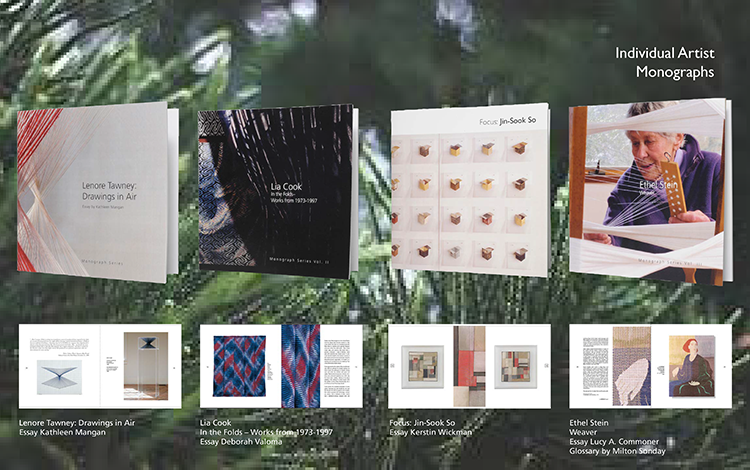

August 10th: Catalog Look back: Cataloging the Canon – Tawney, Stein, Cook, Hicks and So Monographs: 1-3; Focus: 1, Vols. 13, 28

Until then, we’ll keep posting content on arttextstyle and our Facebook, Instagram and Twitter pages.

Stay safe and well! We’ll see you in in person in September and online between now and then.

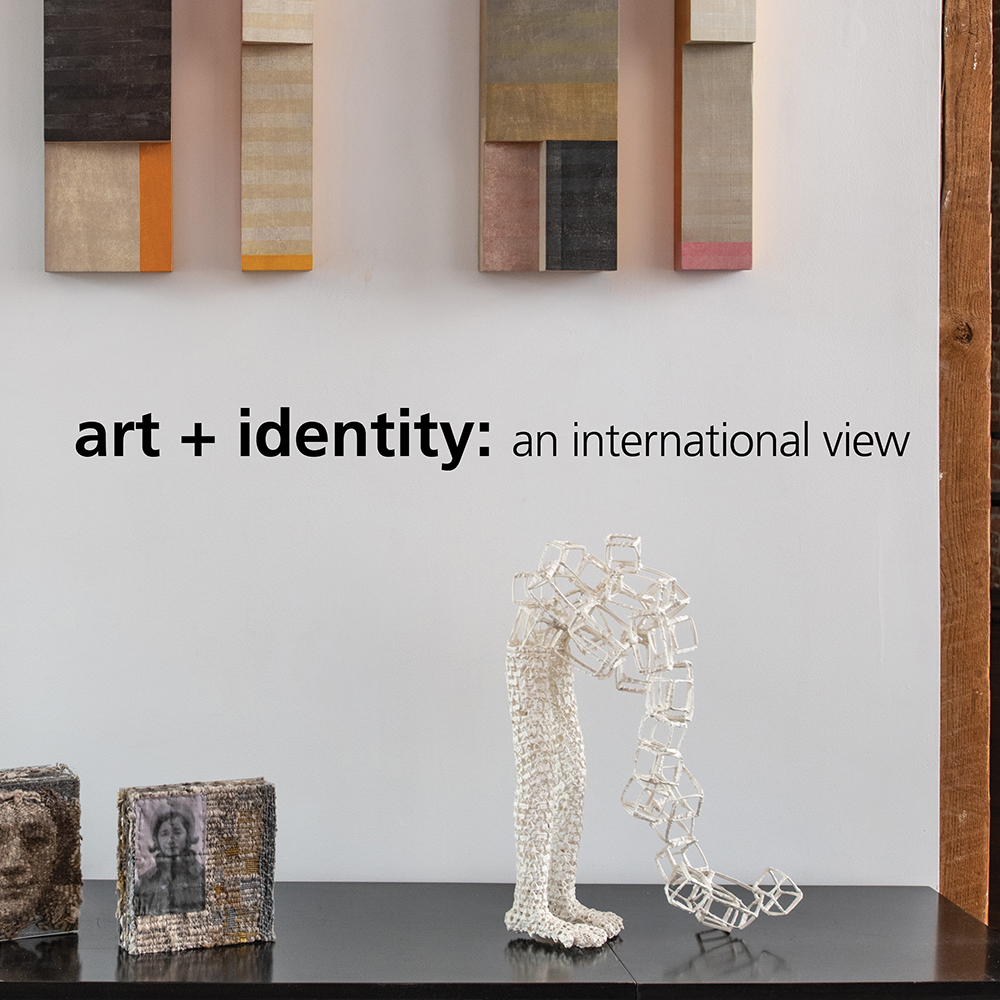

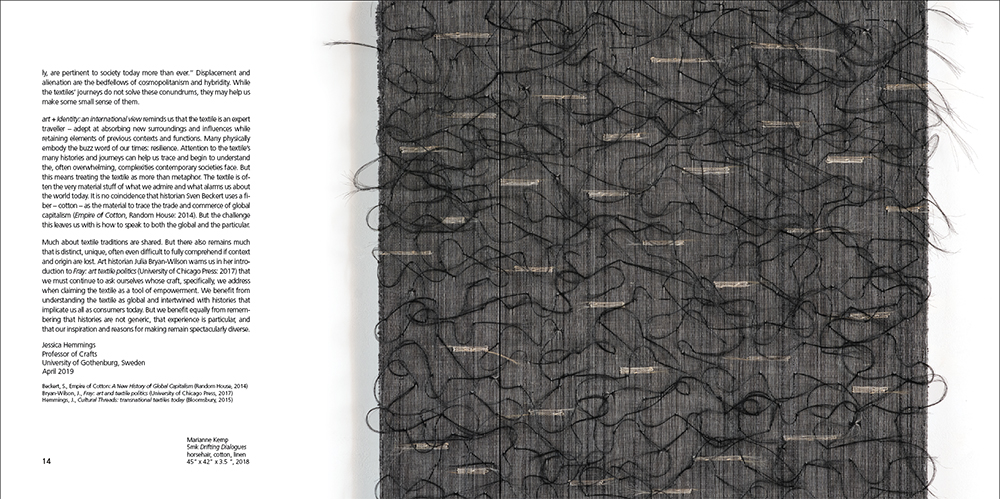

Art & Identity: A Sense of Place

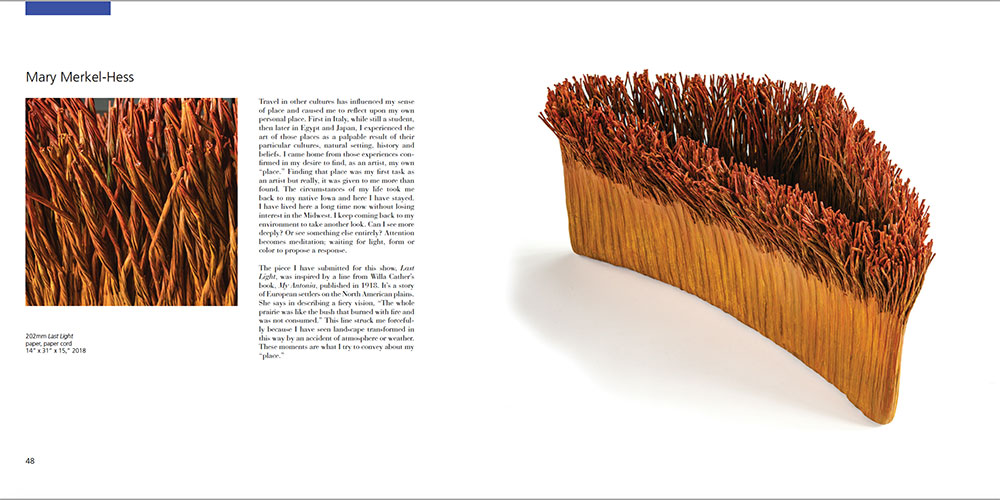

In our 2019 Art in the Barn exhibition, we asked artists to address the theme of identity. In doing so, several of the participants in Art + Identity: an international view, wrote eloquently about places that have informed their work. For Mary Merkel-Hess, that place is the plains of Iowa, which viewers can feel when viewing her windblown, bladed shapes. A recent work made a vivid red orange was an homage to noted author, Willa Cather’s plains’ description, “the bush that burned with fire and was not consumed,” a view that Merkel-Hess says she has seen.

The late Micheline Beauchemin traveled extensively from her native Montreal. Europe, Asia, the Middle East, all influenced her work but depictions of the St. Lawrence River were a constant thread throughout her career. The river, “has always fascinated me,” she admitted, calling it, “a source of constant wonder” (Micheline Beauchemin, les éditions de passage, 2009). “Under a lemon yellow sky, this river, leaded at certain times, is inhabited in winter, with ice wings without shadows, fragile and stubborn, on which a thousand glittering lights change their colors in an apparent immobility.” To replicate these effects, she incorporated unexpected materials like glass, aluminum and acrylic blocks that glitter and reflect light and metallic threads to translate light of frost and ice.

Mérida, Venezuela, the place they live, and can always come back to, has been a primary influence on Eduardo Portillo’s and Maria Davila’s way of thinking, life and work. Its geography and people have given them a strong sense of place. Mérida is deep in the Andes Mountains, and the artists have been exploring this countryside for years. Centuries-old switchback trails or “chains” that historically helped to divide farms and provide a mountain path for farm animals have recently provided inspiration and the theme for a body of work, entitled Within the Mountains. Nebula, the first work from this group of textiles, is owned by the Cooper Hewitt Museum.

Birgit Birkkjaer’s Ode for the Ocean is composed of many small woven boxes with items from the sea — stones, shells, fossils and so on — on their lids. ” It started as a diary-project when we moved to the sea some years ago,” she explains. “We moved from an area with woods, and as I have always used materials from the place where I live and where I travel, it was obvious I needed now to draw sea-related elements into my art work.”

“I am born and raised in the Northeast,” says Polly Barton, “trained to weave in Japan, and have lived most of my life in the American Southwest. These disparate places find connection in the woven fabric that is my art, the internal reflections of landscape.” In works like Continuum i, ii, iii, Barton uses woven ikat as her “paintbrush,” to study native Southwestern sandstone. Nature’s shifting elements etched into the stone’s layered fascia reveal the bands of time. “Likewise, in threads dyed and woven, my essence is set in stone.”

For Paul Furneaux, geographic influences are varied, including time spent in Mexico, at Norwegian fjords and then, Japan, where he studied Japanese woodblock, Mokuhanga “After a workshop in Tokyo,” he writes, “I found myself in a beautful hidden-away park that I had found when I first studied there, soft cherry blossom interspersed with brutal modern architecture. When I returned to Scotland, I had forms made for me in tulip wood that I sealed and painted white. I spaced them on the wall, trying to recapture the moment. The forms say something about the architecture of those buildings but also imbue the soft sensual beauty of the trees, the park, the blossom, the soft evening light touching the sides of the harsh glass and concrete blocks.”