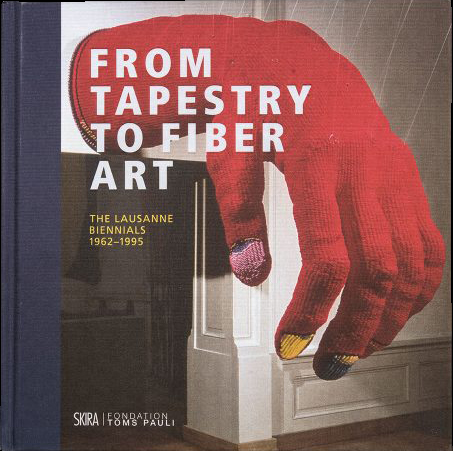

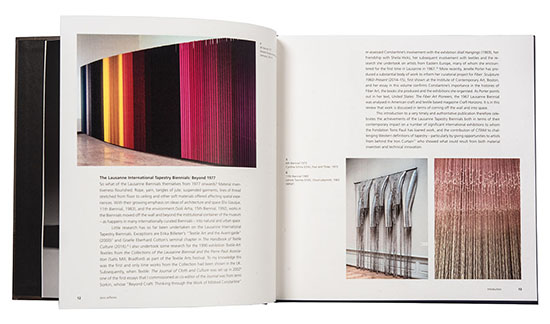

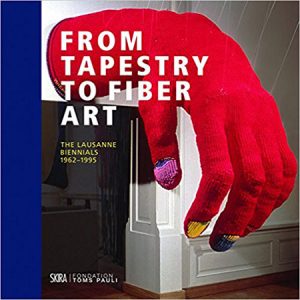

We’ve gathered another year of varied and interesting book recommendations. Gyöngy Laky recommends From Tapestry to Fiber Art: Lausanne Biennials 1962-95 by Giselle Eberhard Cotton and Magali Junet of Fondation Toms Pauli, Lausanne, Switzerland, a book bag recommends as well. “The book describes and illustrates the worldwide exuberance of an art movement that burst, with new energy, onto the world stage of avant garde art in the 1960s and 70s,” she writes. “The title might fool a reader into believing that the artwork within is traditional weaving, but the cover shouts the excitement to be found within its pages. Nearly 6,000 miles away in Berkeley, California, my artist friends and I were inspired and energized by the sculptural works the Biennales Internationale de la Tapisserie presented at the Musee Cantonal des Beaux Arts. Not only were many of the works exhibited monumental, they were also breaking with traditional forms and expanding what this astoundingly flexible art medium could be.” The first of Laky’s friends to be included in one of the Biennales, she recalls, was artist Lia Cook. Several years later, in 1989, Laky’s seven-and-a-half-foot high sculpture, That Word, was exhibited in Lausanne. It’s now housed in the Federal Courthouse in San Francisco.

Cotton and Junet are joined by other contributors who, together, give a thoughtful and well-researched view of the development of this art form from the early Biennales to present day. “Reading this book and viewing the illustrations will provide an understanding of how this movement became so dynamic and why it continues to be so today,” Laky predicts. “Holland Cotter is quoted from a review in 2014, ‘The major art critics are acknowledging what artists have always known, that textile materiality with all its gravity, responsiveness and connections to life and loss holds tremendous capacity to speak to issues of our human condition.'”

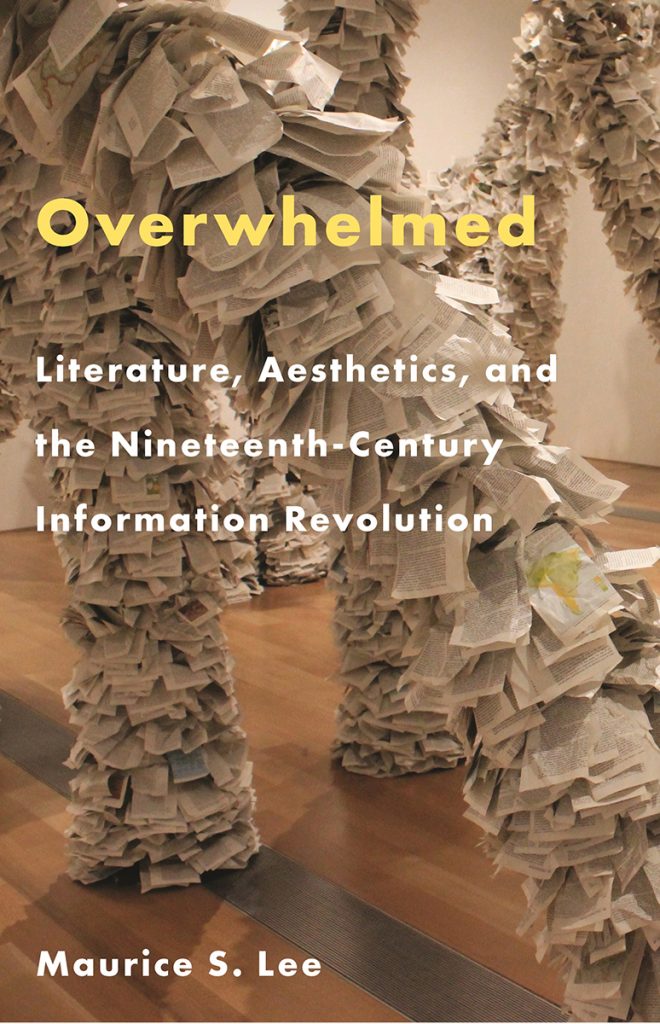

Earlier this year Princeton Press solicited an image of Wendy Wahl’s Branches Unbound, aninstallation at the Grand Rapids Arts Museum 2011, for the cover its forthcoming book by Maurice S. Lee. Wahl writes that she received her copy of Overwhelmed: Literature, Aesthetics and the Nineteenth-Century Information Revolution and, “I am completely delighted. My not-quite-natural trees of deconstructed Encyclopedia Britannica volumes are a fitting image for a book with chapters titled Reading, Searching, Counting and Testing. The author’s historically grounded exploration of the 19th and 20th centuries’ intersection of literature and information offers new ways to think about the 21st century digital humanities.

We received four recommendations from Chris Drury: The Songs of Trees by David George Haskell, The Overstory by Richard Powers, Underland by Robert MacFarlane and The Wisdom of Wolves by Elli H Radinger.

I’m really enjoying The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History by Kassia St Clair at the moment, reports Laura Thomas.

The book offers insights into the economic and social dimensions of clothmaking―and counters the enduring association of textiles as “merely women’s work.”

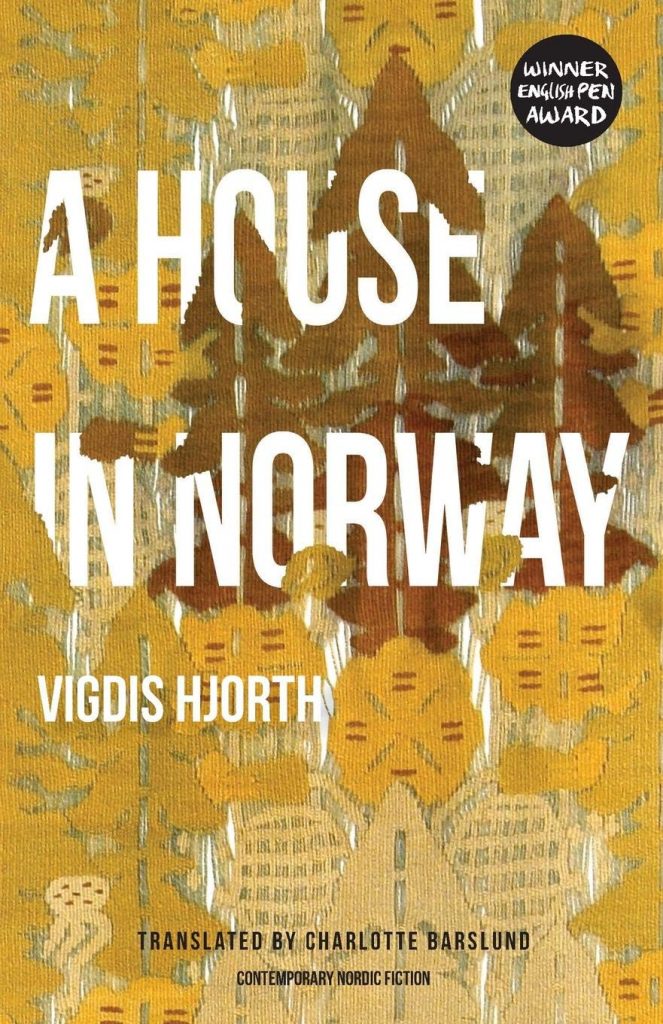

Stéphanie Jacques is reading A House in Norway by Vigdis Hjorth, a novel in which the main character is a woman who is also a textile artist. “You follow her,” she says, “in her creative process and in the difficulties with her neighbors.” Jacques also recommends Hisako Sekijima’s Basketry: Projects from Baskets to Grass Slippers.

“Not really a new one ;-),” she says, “but for me this book is a gift to get back to basketry in the spring.”

“My favorite book this year was The Buried: An Archaeology of the Egyptian Revolution by Peter Hessler,” writes Mary Merkel-Hess. “The author is well known for his previous books about living in China. In 2011, he moved to Cairo with his wife and infant twin daughters to learn Arabic and write about the Middle East and soon found himself caught up in the Arab Spring. This book is about that political upheaval but also a very human story about living in Cairo, exploring ancient archaeological sites as well as navigating the political unrest of modern Egypt. I had the great good fortune to visit Egypt for several lengthy periods in 2007-8 and this book explained much about a culture that I found fascinating, baffling and at times, frustrating.”

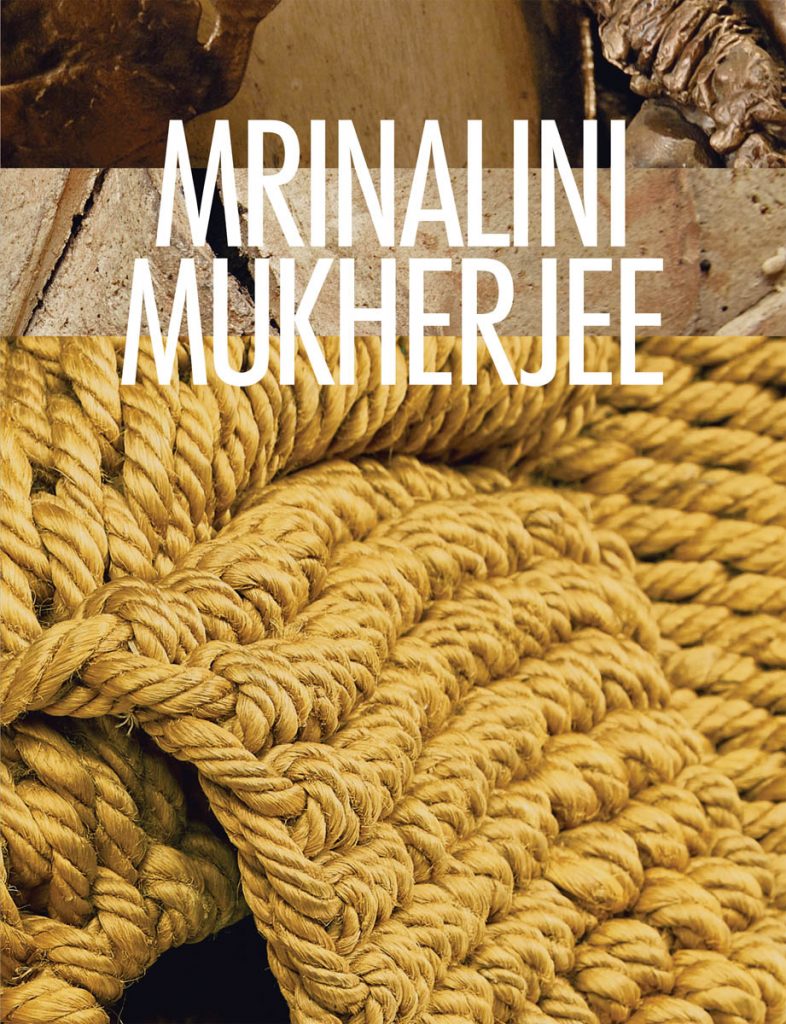

were two books that we were pleased to add to browngrotta arts’ library this year. First was Mrinalini Mukherjee by Shanay Jhaveri. Mukherjee’s work, which is on exhibit in the new galleries at MoMA, was not exhibited in the US until after her death in 2015. As the book notes explain, “Within her immediate artistic milieu in post-independent India, Mukherjee was an outlier artists. Her art remained untethered to the dominant commitments of painting and figural storytelling. Her sculpture was sustained by a knowledge of traditional Indian and historic European sculpture, folk art, modern design, local crafts and textiles. Knotting was the principal gesture of Mukherjee’s technique, evident from the very start of her practice. Working intuitively, she never resorted to a sketch, model or preparatory drawing. Probing the divide between figuration and abstraction, Mukherjee would fashion unusual, mysterious, sensual and, at times, unsettlingly grotesque forms, commanding in their presence and scale.”

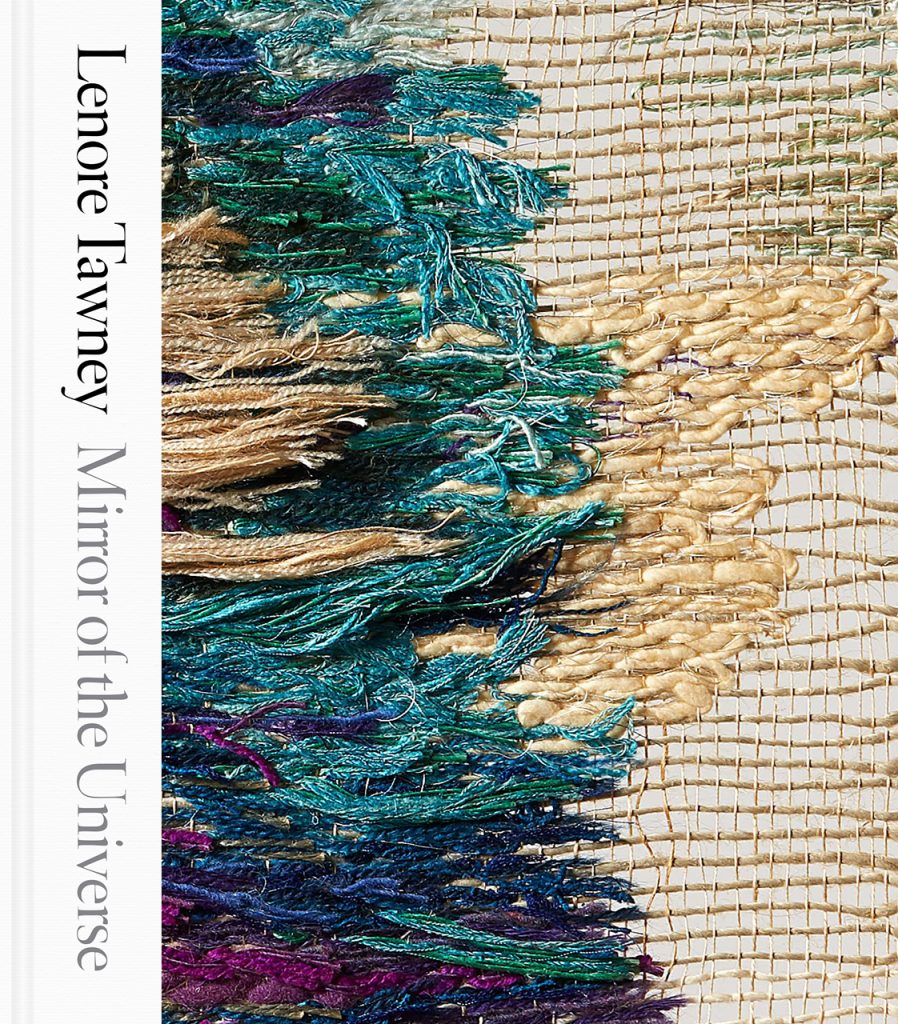

The second was Lenore Tawney: Mirror of the Universe, Karen Patterson, Editor. The book notes, explain that Tawney was known for employing an ancient Peruvian gauze weave technique to create a painterly effect that appeared to float in space rather than cling to the wall. She was known, too, for being one of the first artists to blend sculptural techniques with weaving practices and pioneering a new direction in fiber art, in the process. Tawney has only recently begun to receive her due from the greater art world. She is currently the subject of a four-exhibition retrospective at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center. This book accompanies the exhibition and features a comprehensive biography of Tawney, additional essays on her work and two hundred full-color illustrations, making it of interest to contemporary artists, art historians and the growing audience for fiber art.

The Upanishads, introduced and translated by Eknath Easwaran (Nigiri Press). This collection of teachings is as timely now as it was 2000 years ago. Understanding the following words from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (iv.4.5) could be useful,” she says. You are what your deep, driving desire is. As your desire is, so is your will. As your will is, so is your deed. As your deed is, so is your destiny. The Mundaka Upanishad furnished the motto of the modern Indian nation, she notes, satyam eva jayate, nanritam, Truth alone prevails, not unreality” (iii.1.6).”Perhaps the global collective consciousness will awaken to this concept. I’m trying to remain hopeful.” Wahl adds that for readers interested in one of her favorite materials,

The Upanishads, introduced and translated by Eknath Easwaran (Nigiri Press). This collection of teachings is as timely now as it was 2000 years ago. Understanding the following words from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (iv.4.5) could be useful,” she says. You are what your deep, driving desire is. As your desire is, so is your will. As your will is, so is your deed. As your deed is, so is your destiny. The Mundaka Upanishad furnished the motto of the modern Indian nation, she notes, satyam eva jayate, nanritam, Truth alone prevails, not unreality” (iii.1.6).”Perhaps the global collective consciousness will awaken to this concept. I’m trying to remain hopeful.” Wahl adds that for readers interested in one of her favorite materials,

Books Make Great Gifts 2016

Another year of widely divergent books. Art, biology, history and biography are all represented in the answers we received to the questions we asked of artists that work with browngrotta arts: What books cheered you? Inspired you? Provided an escape?

Dona Anderson, wrote that she is reading Herbert Hoover: A Life by Glen Jeansonne (NAL, New York, 2016) who calls Hoover the most resourceful American since Benjamin Franklin. “I recently had a birthday and remember that my mother went to vote on the day I was born, November 6th, and she voted for Herbert Hoover. Consequently, I started to think about what the political atmosphere was like then — as ours was so crazy and even more so now. When I went to the library in October, the Hoover book was brand new and it appealed to me.” Rachel Max is reading Materiality, edited by Petra Lange-Berndt (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2015), one of the latest additons to the Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art series. It’s a fantastic series. Each volume in the series focuses on a specific theme and contains many thought-provoking essays from theorists and artists. Materiality not only addresses key geographical, social and philosophical issues, but it also examines how artists process and use materials in order to expand notions of time, space and participation. As the publisher notes, “this anthology focuses on the moments when materials become willful actors and agents within artistic processes.” Max has also been dipping into the diaries of Eva Hesse. “They are extremely private and were never meant for publication. But, as a huge fan of her work it is interesting to read her thoughts,” Max writes.

Rachel Max is reading Materiality, edited by Petra Lange-Berndt (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2015), one of the latest additons to the Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art series. It’s a fantastic series. Each volume in the series focuses on a specific theme and contains many thought-provoking essays from theorists and artists. Materiality not only addresses key geographical, social and philosophical issues, but it also examines how artists process and use materials in order to expand notions of time, space and participation. As the publisher notes, “this anthology focuses on the moments when materials become willful actors and agents within artistic processes.” Max has also been dipping into the diaries of Eva Hesse. “They are extremely private and were never meant for publication. But, as a huge fan of her work it is interesting to read her thoughts,” Max writes.

Nimura’s skillful crafting of a can’t-put-it-down narrative of their experiences on two sides of the Pacific is a vividly rich visual, as well as historical, account. She produced for the reader, through captivating descriptions illuminating the startling differences between these two very different cultures, the contrasting worlds we could easily visualize.

Stacy Shiff, Pulitzer Prise-winning author of Cleopatra wrote: “Nimura reconstructs their Alice-in-Wonderland adventure: the girls are so exotic as to qualify as ‘princesses’ on their American arrival. One feels “enormous” on her return to Japan.” It is just this Alice-in-Wonderland aspect of their story that caught my imagination. As in Louis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it is the environment and the material culture that sets the stage for remarkable events. The tangible aspects of two vastly contrasting cultures – intellectually, technically, behaviorally and in terms of the accoutrements of every day life, express well the often conflicting, peculiar and unexpected events in the girls’ lives. The girls move from Japanese clothing, furniture and customs to western style and then back again feeling more comfortable in western settings than in their birth homes kneeling on the floor and lavishly swathed in yards and yards of embroidered silks.

In the late 19th century the US was bursting with inventions and change. Planning begun in the 1850s for the Chicago World’s Fair was well under way, ushering in the Gilded Age of rapid industrial growth, design innovation and expansion of popular culture. A startlingly appropriate time for the girls’ cultural experiment to take place. Nimura, who moved to Japan for three years with her Japanese/American nesei husband, was adept at utilizing her keen sense of design and broad knowledge of the two disparate material cultures. She skillfully brought to life the vast differences between the two civilizations through masterful and insightful descriptions of clothing, hairstyles, furniture, interiors, architecture as well as the cities in which they existed. This, combined with her extensive research, presents the reader with many insights into the relations between the two countries and their intertwined histories through the lives of these exceptional girls and their extraordinary adventures.

As Miriam Kingsberg of the Los Angeles Review of Books wrote, “Daughters… is, perhaps, less a story of Japanese out of place in their country, than of women ahead of their time.” Laky adds that while she was a professor of art and design at the University of California, Davis, she encouraged her students to study abroad. “This book illustrates how education and experience in a foreign country enhances understanding of other cultures and peoples – perhaps more important today than in the 1870s and 80s. I believe travel also greatly inspires creativity.”

It is a sad and exciting story about a typical lonely man in today’s Denmark, she wrote. “Written in a wonderful language – so one can just imagine him, by reading it and it is just as sad as Stoner.

As always, enjoy!