browngrotta arts is devasted by the loss of Sandra Grotta, our extraordinary collector and patron and mother and grandmother. Sandy and her husband Lou have been pivotal in the growth of browngrotta arts through their advice and unerring support. Sandy graduated from the University of Michigan and the New York School of Interior Design. For four decades, she provided interior design assistance to dozens of clients — many through more than one home and office. She encouraged them to live with craft art, as she and Lou had done, placing works by Toshiko Takezu, Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, Helena Hernmarck, Gyöngy Laky, Markku Kosonen, Mary Merkel-Hess and many other artists in her clients’ homes. Among her greatest design talents was persuading people to de-accession pieces they had inherited, but never loved, to make way for art and furnishings that provided them joy. Sandy was a uniquely confident collector and she shared that conviction with her clients.

Her own collecting journey began in the late 1950s, when she and Lou first stepped into the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York City after a visit to the Museum of Modern Art. “The Museum’s exhibitions, many of whose objects were for sale in its store, caused a case of love at first sight. It quickly became a founding source of many craft purchases to follow,” Sandy told Patricia Malarcher in 1982 (“Crafts,” The New York Times, Patricia Malarcher, October 24, 1982). It was a walnut table ”with heart” on view at MoCC that would irrevocably alter the collectors’ approach. The table was by Joyce and Edgar Anderson, also from New Jersey. The Grottas sought the artists out and commissioned the first of many works commissioned and acquired throughout the artists’ lifetimes, including a roll-top desk, maple server and a sofa-and-table unit that now live in browngrotta arts’ gallery space. She followed the advice she would give to others: “When we saw the Andersons’ woodwork,” Sandy remembered, “we knew everything else had to go,” Sandy told Glenn Adamson. From the success of that first commission, the Grottas’ art exploration path was set. The Andersons introduced the Grottas to their friends, ceramists Toshiko Takaezu and William Wyman. “The Andersons were our bridge to other major makers in what we believe to have been the golden age of contemporary craft,” Sandy said, “and the impetus to my becoming our decorator.”

When Objects USA: the Johnson Wax Collection, opened in New York in 1972 at MoCC, by then renamed the American Craft Museum, the Grottas began discovering work further afield. ”Objects USA was my Bible,” Sandy told Malarcher describing how she would search out artists, ceramists, woodworkers and jewelers. A trip to Ariel, Washington, led the Grottas to commission an eight-foot-tall Kwakiutl totem pole for the front hall by Chief Don Lelooska. Sandy ordered a bracelet by Charles Loloma from a picture in a magazine. ”I always got a little nervous when the packages came, but I’ve never been disappointed,” Sandy told Malarcher. ”Craftsmen are a special breed.” Toshiko Takaezu, as an example, would require interested collectors like the Grottas to come by her studio in Princeton, NJ, a few times first to “interview” before she’d permit them to acquire special works. It took 15 years and several studio visits each year for the Grottas to convince the artist to part with the “moon pot” that anchors their formidable Takaezu collection. Jewelers Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins in the UK also became dear friends as Sandy developed a world-class jewelry collection. At one point, in a relationship that included weekly transatlantic calls, Sandy told Wendy she needed “everyday earrings.” Wendy responded with earrings for every day – seven pairs in fact. “For me, the surprise was that they found me,” says John McQueen. “I lived in Western New York state far from the hubbub of the art world.” McQueen says that he discovered they the Grotta’s were completely open to any new aesthetic experience. “from that moment, we established a strong connection, that has led to a rapport that has continued through the years – a close personal and professional relationship.”

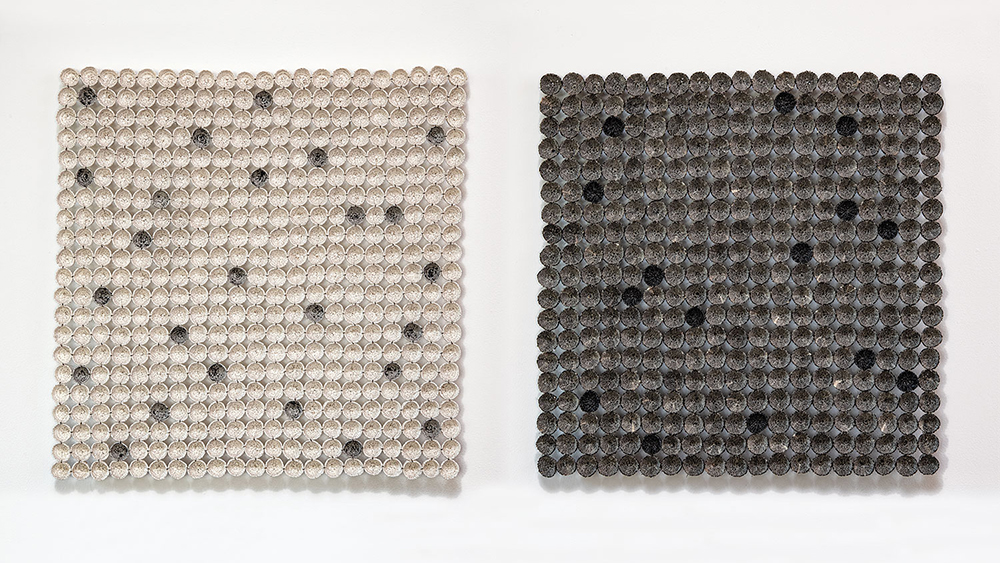

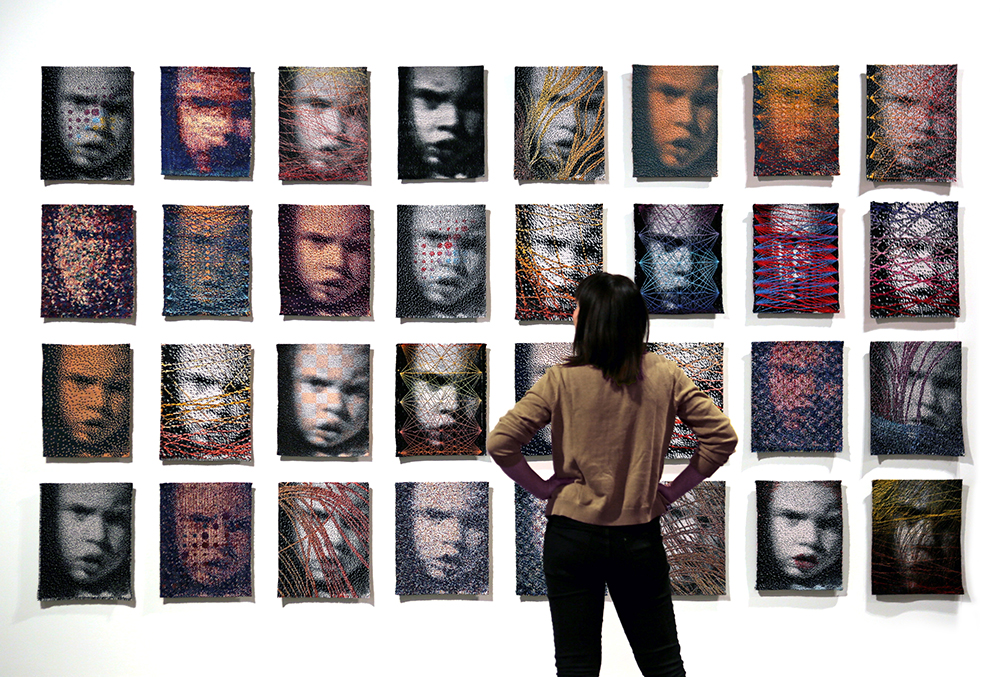

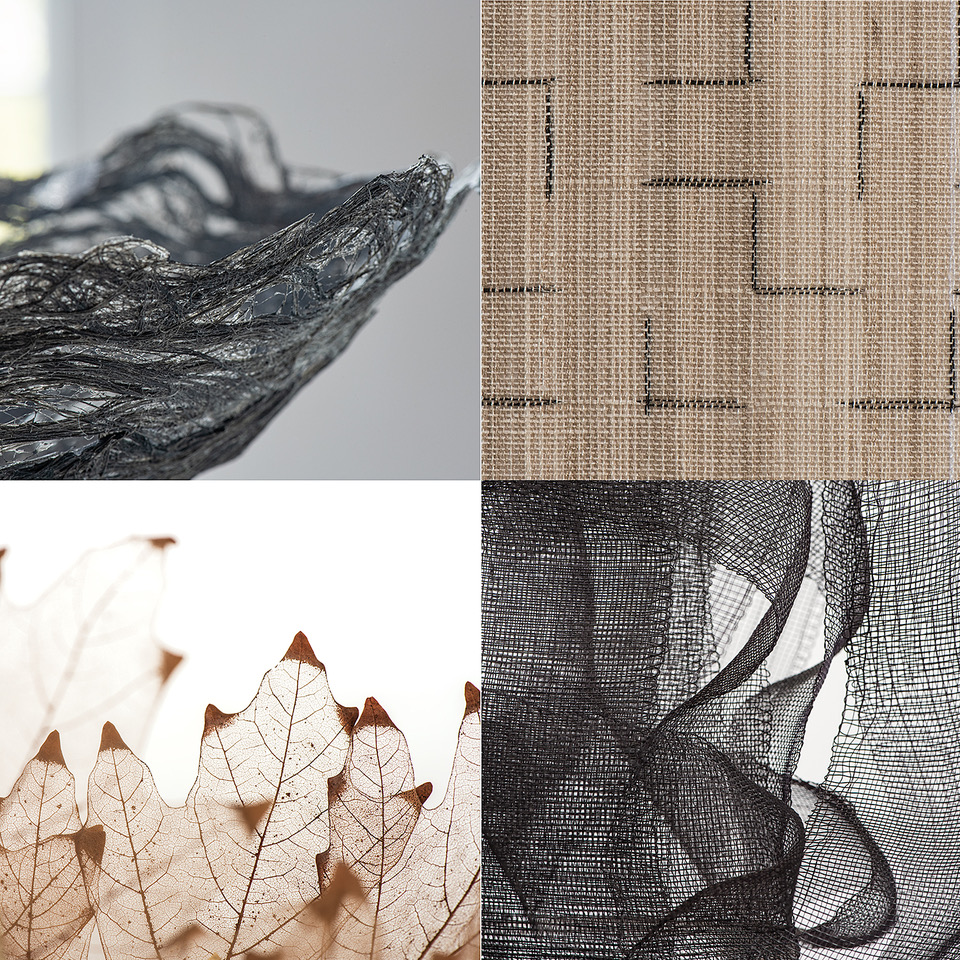

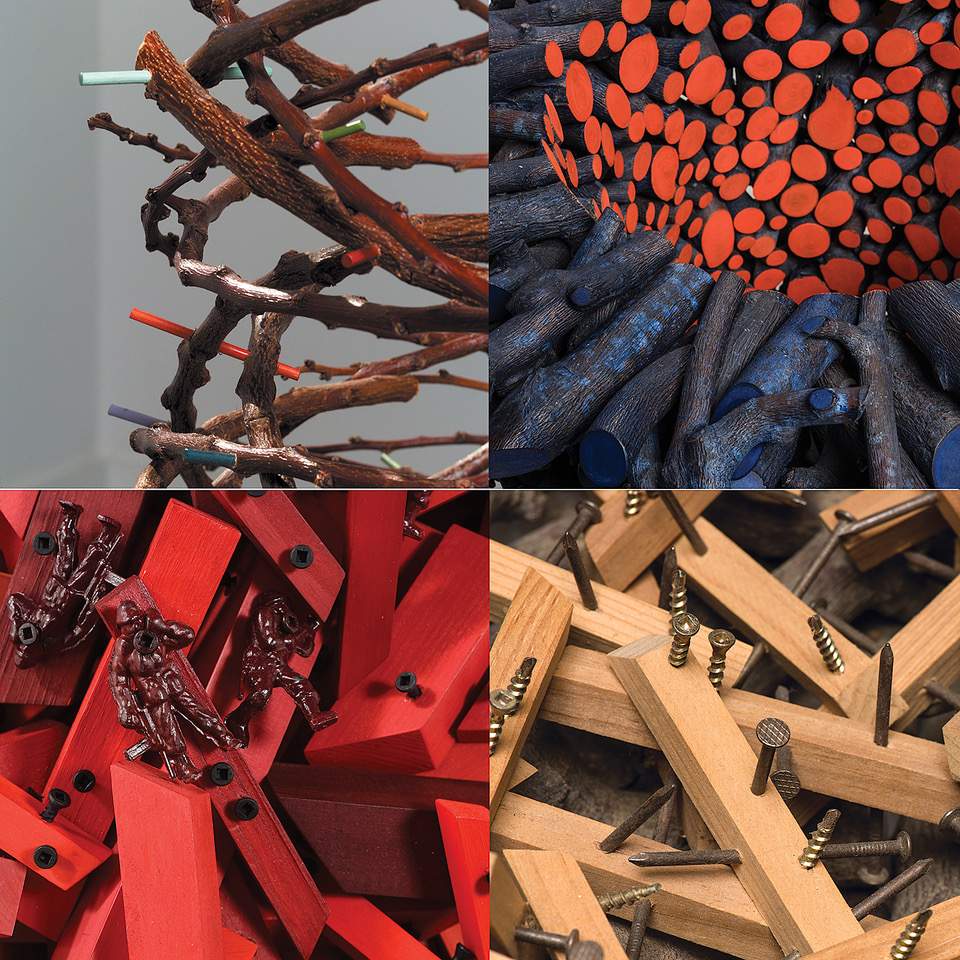

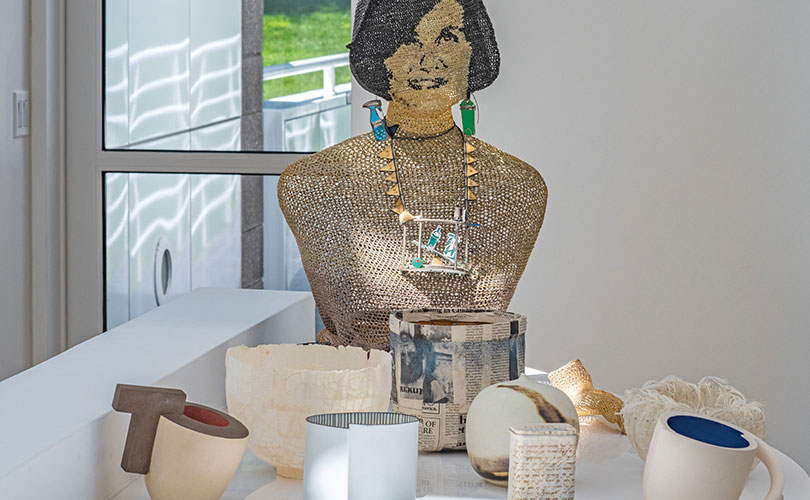

Their accumulation of objects has grown to include more that 300 works of art and pieces of jewelry by dozens of artists, and with their Richard Meier home, has been the subject of two books. The most recent, The Grotta Home by Richard Meier: A Marriage of Architecture and Craft, was photographed and designed by Tom Grotta of bga. They don’t consider themselves collectors in the traditional sense, content to exhibit art on just walls and surfaces. Sandy and Lou’s efforts were aimed at creating a home. They filled every aspect of their lives with handcrafted objects from silver- and tableware to teapots to clothing to studio jewelry and commissioned pillows, throws and canes, a direction she also recommended for her interior design clients. The result, writes Glenn Adamson in The Grotta Home,”is a home that is at once totally livable and deeply aesthetic.” Among the additional artists whose work the Grottas acquired for their home were wood worker Thomas Hucker, textile and fiber artists Sheila Hicks, Lenore Tawney and Norma Minkowitz, ceramists Peter Voulkos, Ken Ferguson and William Wyman and jewelers Gijs Bakker, Giampaolo Babetto, Axel Russmeyer and Eva Eisler. They have traveled to Japan, the UK, Czechoslovakia, Germany and across the US to view art and architecture and meet with artists.

Perhaps their most ambitious commission was the Grotta House, by Richard Meier. Designed to house and highlight craft and completed in 1989, it is a source of constant delight for the couple, with its shifting light, showcased views of woodlands and wildlife and engaging spaces for object installation. The Grottas were far more collaborative clients than is typical for Meier. “From our very first discussions,” Meier has written,”it was clear that their vast collection of craft objects and Sandy’s extensive experience as an interior designer would be an important in the design of the house.“ The sensitivity with which the collection was integrated into Meier’s design produced “an enduring harmony between an ever-changing set of objects and they space they occupy.” The unique synergy between objects and architecture is evident decades later, even as the collection has evolved. Despite his “distinct — and ornament-free — visual language, Meier created a building that lets decorative objects take a leading role on the architectural stage,” notes Osman Can Yerebakan in Introspective magazine (“Tour a Richard Meier–Designed House That Celebrates American Craft,” Osman Can Yerebakan, Introspective, February 23, 2020). The house project had an unexpected benefit — a professional partnership between Sandy and Grotta House project manager, David Ling, that would result in memorable art exhibition and living spaces designed for the homes and offices of many of Sandy’s design clients.

Sandy and Lou became patrons of the American Craft Museum in 1970s. As a member of the Associates committee she organized several annual fundraisers for the Museum, including Art for the Table, E.A.T. at McDonald’s and Art to Wear, sometimes with her close friend, Jack Lenor Larsen, another assured acquirer, as co-chair. At the openings, she would sport an artist-made piece of jewelry or clothing, sometimes both, and often it was an item that arrived or was finished literally hours before the event. “I wear all my jewelry,” she told Metalsmith Magazine in 1991 (Donald Freundlich and Judith Miller, “The State of Metalsmithing and Jewelry,” Metalsmith Magazine, Fall 1991) “I love to go to a party where everyone is wearing pearls and show up in a wild necklace …. I have a house brooch by Künzli – a big red house that you wear on your shoulder. I can go to a party in a wild paper necklace and feel as good about it as someone else does in diamonds.” Sandy served on the Board of the by-then-renamed Museum of Arts and Design, stepping down in 2019.

From its inception, Sandy served as a trusted advisor, cheerleader and cherished client to browngrotta arts. She introduced us to artists, to her design clients and Museum colleagues. Questions of aesthetic judgment — are there too many works in this display? too much color? does this work feel unfinished? imitative? decorative? — were presented to her for review. (She was unerring on etiquette disputes, too.) The debt we owe her is enormous; the void she leaves is large indeed. We can only say thank you, we love you and your gifts will live on.

You can learn more about Sandy’s life and legacy on The Grotta House website: https://grottahouse.com and in the book, The Grotta Home by Richard Meier: A Marriage of Architecture and Craft available from browngrotta at: https://store.browngrotta.com/the-grotta-home-by-richard-meier-a-marriage-of-architecture-and-craft/.

The family appreciates memorial contributions to the Sandra and Louis Grotta Foundation, Inc., online at https://joingenerous.com/louis-and-sandra-grotta-foundation-inc-r5yelcd or by mail to The Louis and Sandra Grotta Foundation, Inc., P.O. Box 766, New Vernon, NJ 07976-0000.