Baiba Osite and Mercedes Vicente are two more artists we are pleased to introduce whose work is included in Allies for Art: Work from NATO-related countries, our upcoming Art in the Barn exhibition this Fall.

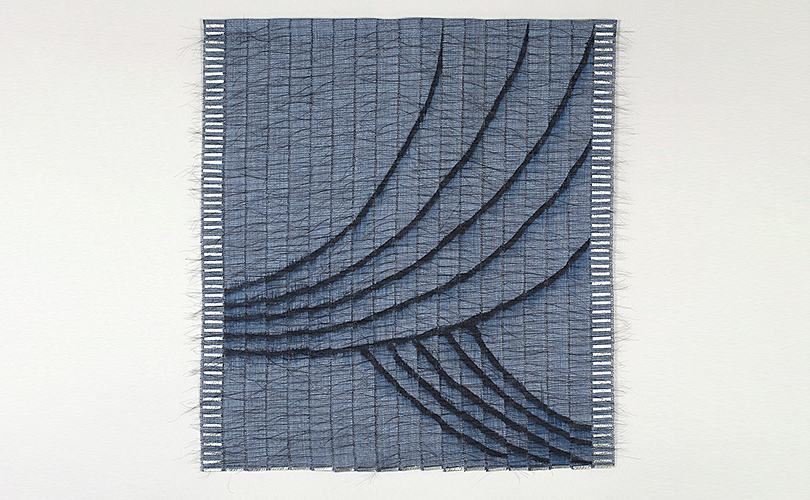

Baiba Osite is from Latvia. Since graduating from the Latvian Academy of Art Textile Department and finishing her Master’s degree, she has participated in art exhibitions worldwide. Among those exhibitions were the biennial Textil Art of Today which traveled to Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, International Fiber Art Biennial, From Lausanne to Beijing, China, the World Textile Art Biennial, Madrid, Spain, and the 3rd International Textile Competitions, Kyoto, Japan. She works in education and is a member of Latvian Artist Union and Textile Association. Recently, she has enriched her experience in two valuable residencies: ”Cite des Arts” in Paris and “Textilsetur” residency in Iceland. Osite leads a folk art textile studio. Partipants there spent two months sewing a safety net for Ukrainian national guards, a project they will continue again in the fall.

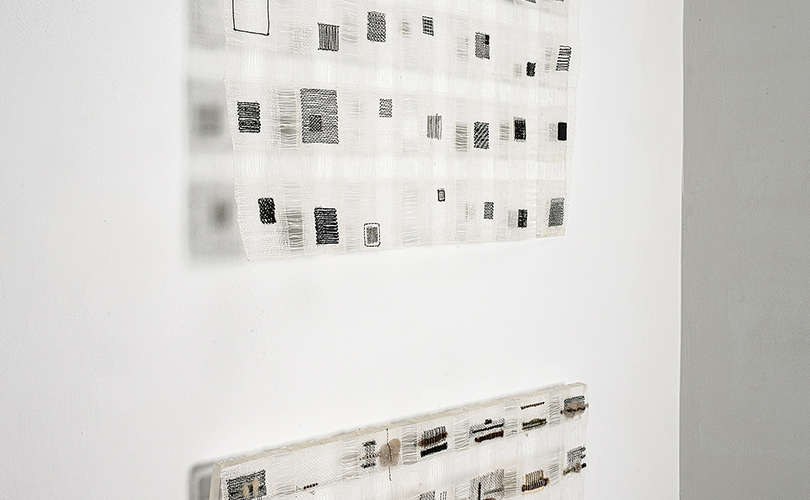

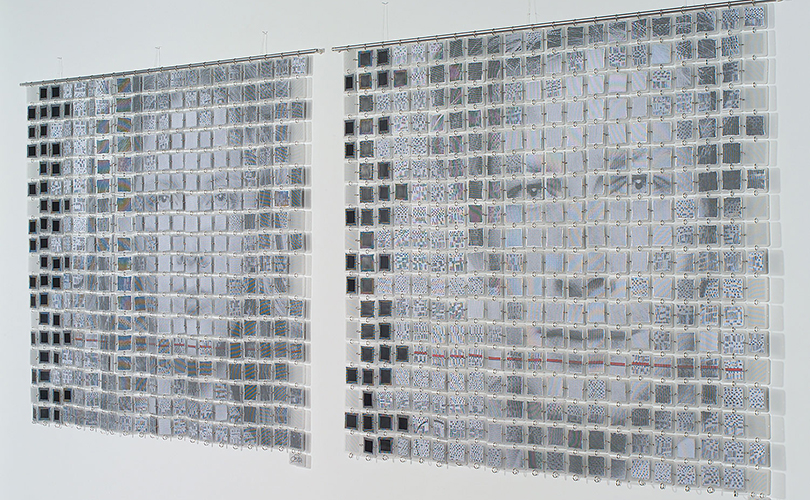

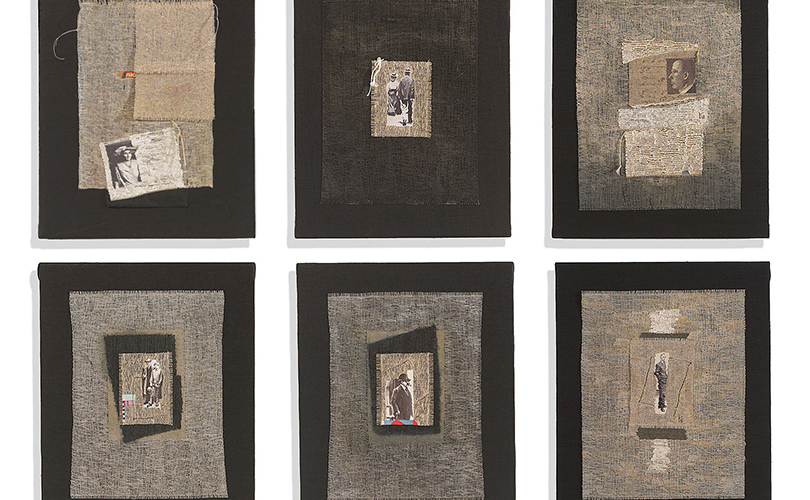

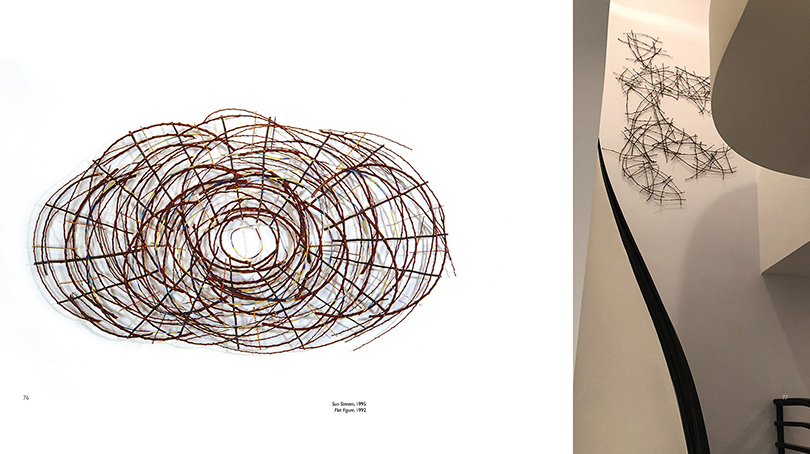

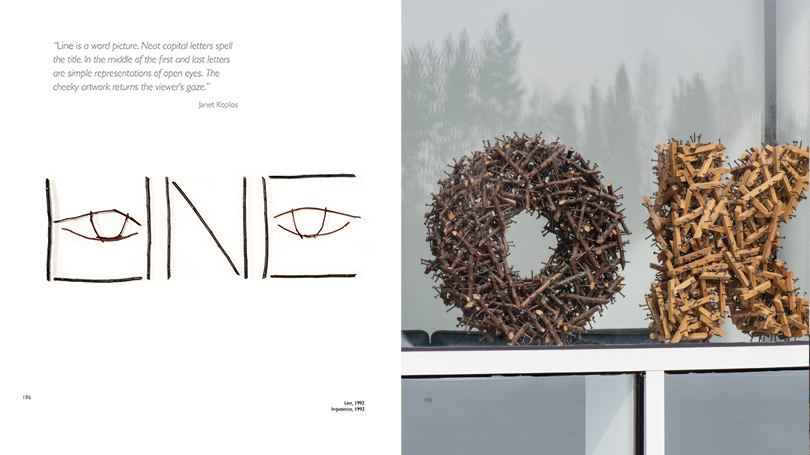

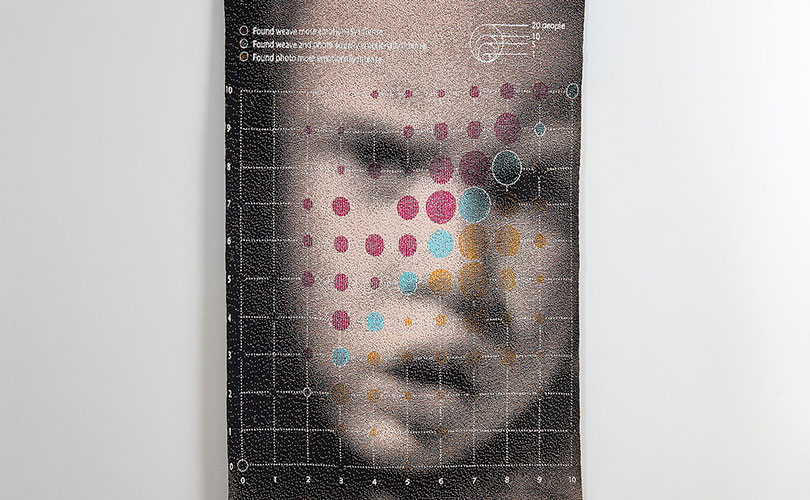

Osite is known for her work with different fiber materials including driftwood, glass beads, wire, metal spirals, wool and linen. “Historically,” Osite says, “these materials were used in household textiles. I assign to them contemporary understanding and concept.” The various materials are sources of inspiration for Osite to create new works. Her work is also inspired by traditional ethnographic patterns and influenced by different cultures.

The works that Osite will exhibit in Art for Allies are made from driftwood segments that she collects on the shore of the Baltic Sea. One of Osite’s driftwod works, Substantia, was awarded the Acquisition Prize of Contextile 2018, the Contemporary Textile Art Biennial in Portugal. The work was based “on the paradoxical game between ‘being’ and ‘not being’ and the transformation of ‘being,’” Osite explains. Driftwood works like City Walls reflect her propensity for dissecting patterns from nature and recreating them in a new form. Osite created City Walls for the World Textile Association Biennial, Sustainable City in Madrid in 2019.

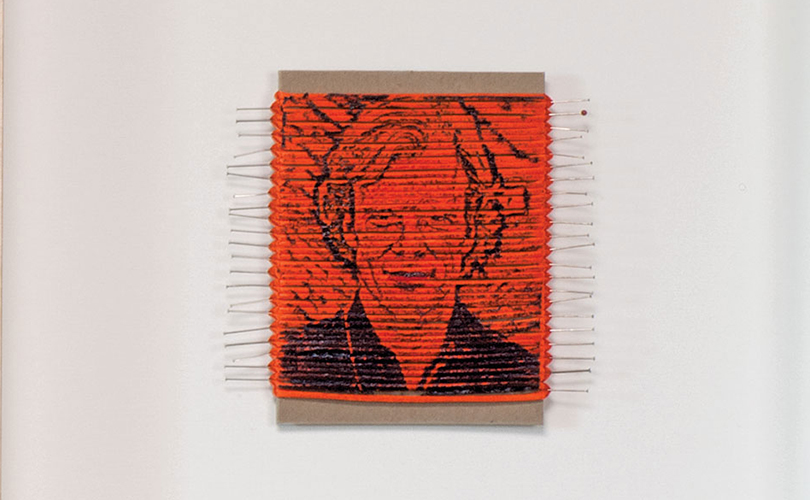

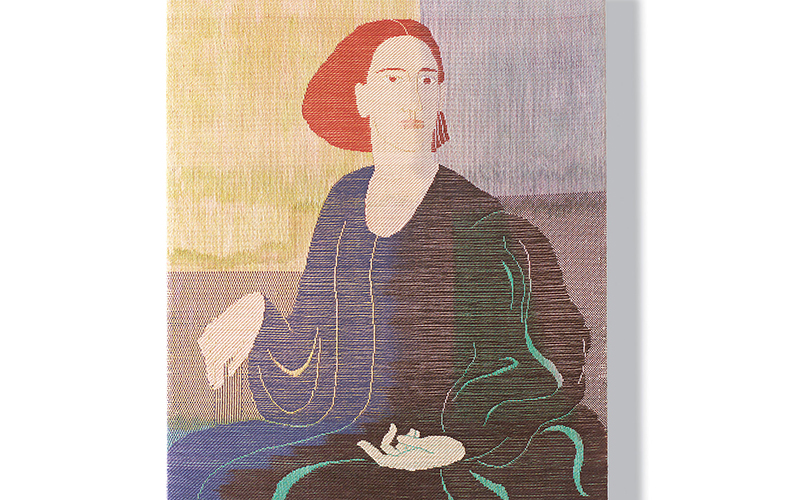

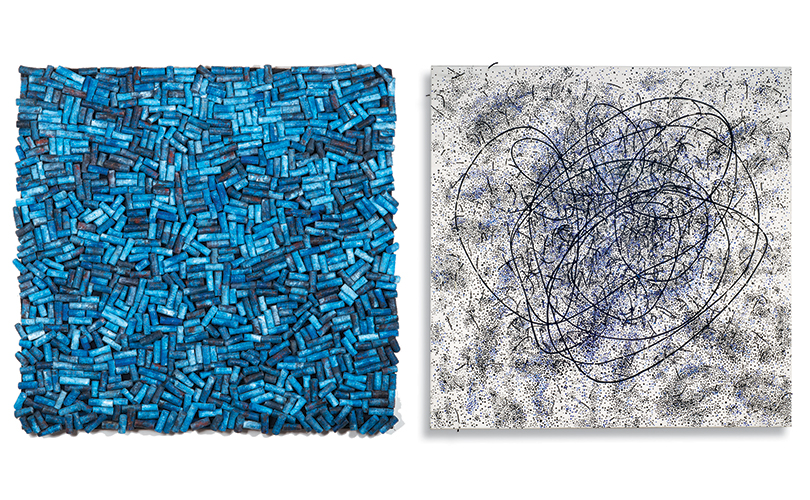

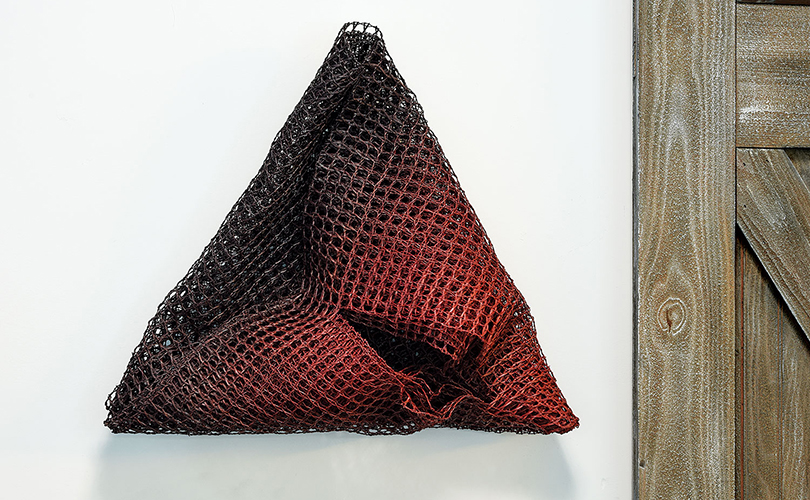

Mecedes Vicente is an artist based in Galicia, Spain, specializing in craft art. A regular participant in exhibitions around the world, Vicente is currently working with wood and textile projects, including sculptures made of canvas strips. Her work is influenced by the French artist Pierre Huyghe.

Born in Madrid in 1958, Mercedes Vicente’s family moved to various locations in Spain during her youth, an experience that pushed her to approach learning in a fundamentally self-taught manner. Initially, her art was pictorial, but it evolved into sculpture, with canvas as her primary medium. She loves the elastic, organic, flexible and translucent properties of the fabric with which she works. She must first prepare the untreated canvas by gluing it and priming it.

“When I started using this technique, I realised that people were amazed by such a manual process,” she says. “Then I started to think that what I was doing was within the realms of craftsmanship, art and design.” She chose fabric in part because it was easy to get hold of, since a member of her family worked in a factory producing canvas.

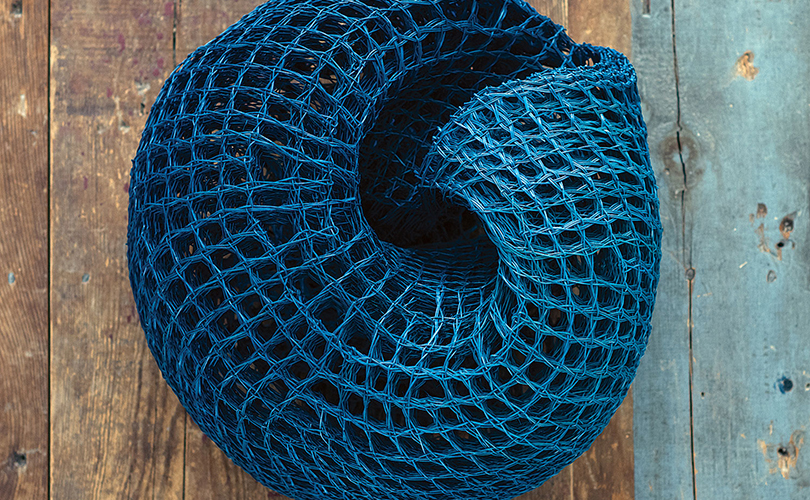

Vicente’s works often being or adapt a spiral shape. She told Thought Object about the significance of that shape. “Space is where the spiral arranges itself and where it’s subject to effects that impact it as if it were an architectural work: it’s exciting and moving how light acts upon the figure and how you can imagine yourself for a moment inside the spiral,” she points out. “This is part of the experience of space, dimensions, and volumes. It’s also the material with its finish and configuration and moreover, it’s the empty space around it where emotion lives.”

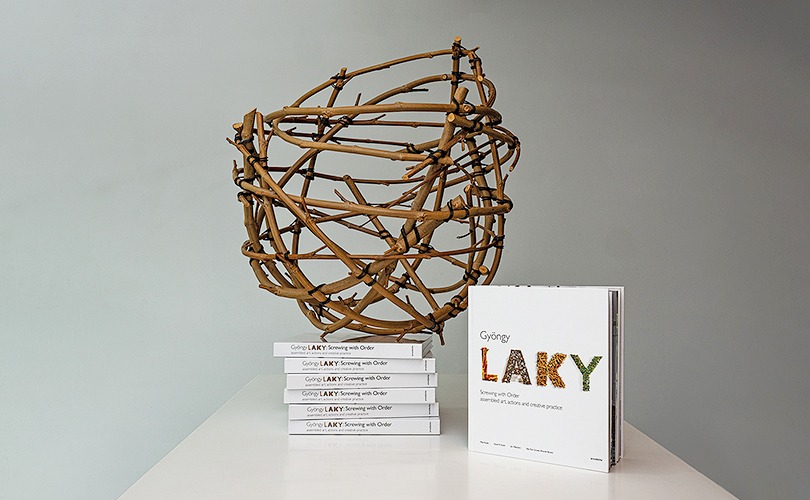

Allies for Art: Work from NATO-related countries (browngrotta arts, October 8 – 16, 2022) will feature nearly 50 artists and highlight work from 21 countries in Eastern and Western Europe, 18 countries in NATO and the three current applicants. The artists in the exhibition reflect diverse perspectives and experiences. Allies for Art will include art created under occupation, in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, art by those who left Hungary, Romania and Spain while occupied, and art by other artists who left Russia in later years. Allies for Art: Work from NATO-related Countries will also include works created by artists. like Osite and Vicente, who are currently working in Europe. Reserve your spot in Eventbrite.