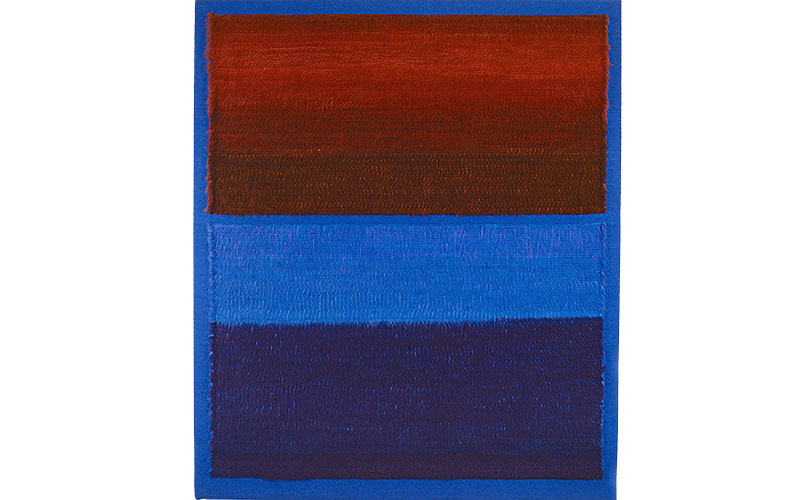

Recent exhibitions of Mark Rothko’s work, a massive Rothko retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, comprising more than 100 paintings (through October 18th) and Mark Rothko Works on Paper at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., have brought another wave of attention to the deservedly acclaimed artist. Rothko is best known for his color field paintings that feature irregular and painterly rectangular regions of color, produced from 1949 to 1970. “[R]ectangles of dazzling, unearthly color floating one above the other,” that “lend themselves to … an intense, even religious devotion …” wrote Anthony Majanlahti, in Hyperallergic in March 2024.

Rothko’s work has been a potent influence for several of the international artists who have worked with browngrotta arts. Mariette Rousseau-Vermette’s appreciation is perhaps the most literal. The Canadian artist saw an exhibition of the Rothko’s works in Italy in 1958. It was pivotal in inspiring her “to produce strictly artistic works in weaving,” Anne Newlands wrote in Weaving Modernist Art: The Life and Times of Mariette Rousseau-Vermette (Firefly Books, Richmond Hill, Ontario, 2023, p. 32). Throughout Rousseau-Vermette’s life, Newlands says, Rothko was a powerful influence, “triggering compositions with floating blocks of color, soft edges and her signature brushed wool technique to create a blending of colors and a sense of inner light.” Her interest in Rothko “marked her as a colorfield artist-weaver, fueling her ambition to create large-scale tapestries that would engulf the viewer and employ powerful chromatic contrasts of light and dark to evoke an emotional response.”

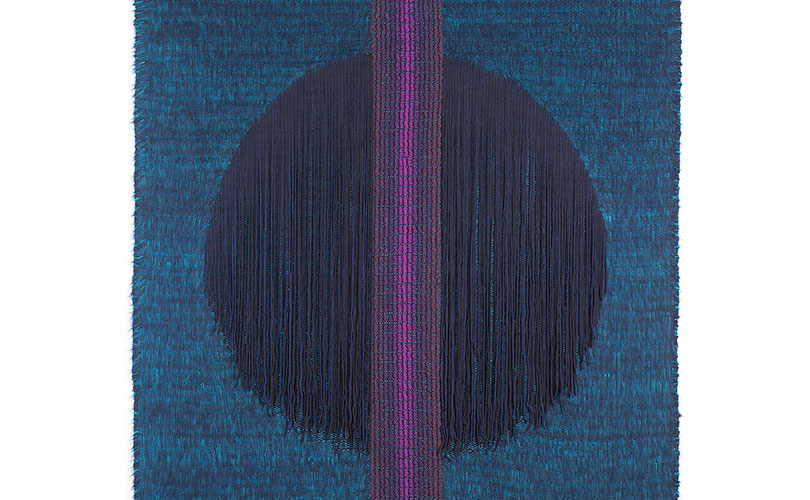

Rousseau-Vermette’s work Hommage á Rothko was included in Three Canadian Fiber Artists at the Art Gallery of Windsor, Canada in 1981. In 1997, browngrotta arts exhibited Si Rothko m’ était conté une histoire, 1997 at the SOFA art fair in Chicago, Illinois. “With its large scale, densely brushed woolen surface and stacked blocks of color in velvety jewel tones of deep blues and shadowy reds,” Newlands notes, “it underlined the artist’s enduring admiration of Rothko and her lasting desire to create contemplative, atmospheric tapestries.” The tapestry was purchased at the exhibition and later donated to the Art Institute of Chicago.

American artist, Sheila Hicks, who studied with famed color theorist, Josef Albers, also found Rothko’s use of color an inspiration. She was one of the artists included in the 2021 exhibition, Artists and the Rothko Chapel: 50 Years of Inspiration, at the Moody Center of the Arts at Rice University, in Houston, Texas. “Like music, color is the almighty mood determinant: It sets the stage for emotional depth and inspires an expansive range of responses from joy to despair, from a sense of wonder to an affirmation of life,” Hicks has said. “Rothko’s painting did this for me.” (“5 Artists on the Influence of Mark Rothko,” Artsy Editorial, April 13, 2021).

Color is an important element of Lija Rage’s work, too. Rage is from Latvia, as was Rothko. In her one-person exhibition at the Mark Rothko Art Centre, Daugavpils, Latvia, entitled Colours, she described how she determines the colors she uses. “For digital printing,” Rage said in conjunction with Colours, “I use my own photographs. Real to begin with and taken in different seasons, they are processed until I’m left with blurred color fields. Color as a flash, an abstract field, a vision.” The color in her fiber works are drawn from nature. “Green – the woods outside my window; blue – the endless variety of the sea; orange – the sun in a summer sky; brown, grey and black – fresh furrows and the road beneath the melting snow; red – the roses in our gardens.”

The Mark Rothko Art Centre also hosted Indian artist Neha Puri Dhir. In 2016, she was chosen with eight other participants to participate in an International Textile Art Symposium. ” I was fortunate to attend an art residency at Mark Rothko Art Centre as part of Textile Art Symposium at Daugavpils, Latvia and got an opportunity to study the great artist in the environs of his birthplace,” Dhir writes.

“What Rothko brought to the world was very unique and personal. He looked at his works as an environment in themselves, works which transcended emotions and he did not like any academic dissection of his art. At Daugavpils, understanding his world and spending hours trying to seek a glimpse of his mind, re-affirmed the beauty of a unique creative self-expression for me. I realized what Rothko was expressing was nothing but very basic human emotions which invariably will always be layered and multifaceted. The layering of colors and mixing of oil and egg-based paints for expression has all left an indelible mark on my art,” Dhir says.

Gizella Warburton of the UK and Gudrun Pagter of Denmark also reference Mark Rothko as a influence. “He manages to create a great image-based experience with his clean and focused divisions and distinguished color schemes,” Pagter says. UK artist, Rachel Max, read From the Inside Out by Rothko’s son, Christopher. Max says the artist’s meditative sensitivity and use of color inspires her. She was particularly interested in the chapter on the emotional power of Rothko’s paintings and its parallels to music. Christopher Rothko draws similarities between Mozart’s melodies and his father’s transparent textures, clarity, and purity of from in order to give what he calls greater expression – for both artist and composer alike nothing was added unnecessarily. “I grew up surrounded with music,” Max writes. “The relationship between music and weaving is something I have been exploring and this particular essay resonated with me.”

While Rothko is best known for his paintings, he also created nearly 3,000 works on paper (the subject of the National Gallery exhibition). He mounted them similarly to how his canvases would be hung. “They’re attached to either a hardboard panel or linen, and wrapped around a stretch or a strainer to give them this three-dimensional presence,” says curator Adam Greenhalgh said. Another parallel to contemporary fiber art work, in which dimension is often an element.

Rothko’s son, Christopher, has said something about viewing his father’s works that applies to anyone for whom Rothko is an influence. “I often think about going to Rothko exhibitions,” he told CBS News. “It’s a great place to be alone together. Ultimately, it’s a journey we all make ourselves, but so much richer when we do it in the company of others.”