Material Matters: Kibiso, Japanese Silk

This is another installment in our series of information on materials used by artists who work with browngrotta arts including horsehair, agave and today, kibiso silk.

Kibiso refers to silk drawn from the outer layer of the silk cocoon, considered “waste” in compared to the smooth filament that makes up the inner cocoon. This thick cocoon layer is also called choshi in Japan, frison in the USA, knubbs in Great Britain, sarnak in India, frissonette in France, and strusa in Italy. In the past, it had been discarded as too tough to loom.

Since 2008, NUNO, the innovative Japanese textile firm, has focused on the use of kibiso. Working with elderly women in Tsuruoka, one of Japan’s last silk-weaving towns, NUNO started a kibiso hand-weaving project. These women set up looms in their garages and kitchens for extra family income, and made woven bags out of the thick, stiff kibiso yarn, as well as handknit hats. NUNO has refined kibiso down to a thickness that allows automatic machine looming, resulting in a whole line of new fabrics, most of which have normal silk warps and kibiso wefts. As part of an effort to revitalize Japan’s once-booming silk trade, NUNO’s head designer, Reiko Sudo, also works with the Tsuruoka Fabric Industry Cooperative on a variety of products under the “kibiso” label.

The fiber is water repellent and UV resistant. Machine-made kibiso yarn was originally produced in Yokohama, writes the Cooper-Hewitt, the center of silk exportation in Japan between the 1860s until the 1920s. This silk waste was considered a high-quality material, and produced good quantities with little waste. However, the industrial process to obtain this fiber was not considered cost-effective and it progressively lost its appeal until Reiko Sudi and NUNO addressed revival of kibiso yarn production. Kibiso comes from about 2% of the silk cocoon, Slow Fiber Studio says. It contains an especially high amount of sericin protein, which means it takes dye very strongly and offers great opportunities to explore body and texture. It’s used in its original, more rigid state, to create sculptural forms, or degummed with soda ash to soften the fibers.

Kiyomi Iwata is an artist who has explored the artistic opportunities that kibsio presents. Iwata was born in Kobe, Japan. She immigrated to the US in 1961. She studied at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond and the Penland School of Craft. In the 1970s, she and her family relocated to New York City, where she studied at the New School for Social Research and the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. She returned to Richmond in 2010 and began working on a body of work using kibiso. She explained to Amanda Dalla Villa Adams in an interview for Sculpture Magazine (“Qualities of the Unsaid: A Coversation with Kiyomi Iwata,” Sculpture Magazine, Amanda Dalla Villa Adams, February 11, 2021) what apealed to her about the material.

“Kibiso has a very different attraction for me, contrary to my usual silk organza, which is woven from fine silk thread,” Iwata told Adams. The silkworms produce 3,000 meters of thread during their lifetime, and kibiso is the very first 10 meters. “By using kibiso,” the artist says, “I am using the silkworm’s whole life output, which is gratifying. I went back to the traditional manner of using thread to weave. Whatever the thread had from its previous life, such as the silkworm’s cocoon, I left it where it was and dyed the thread.”

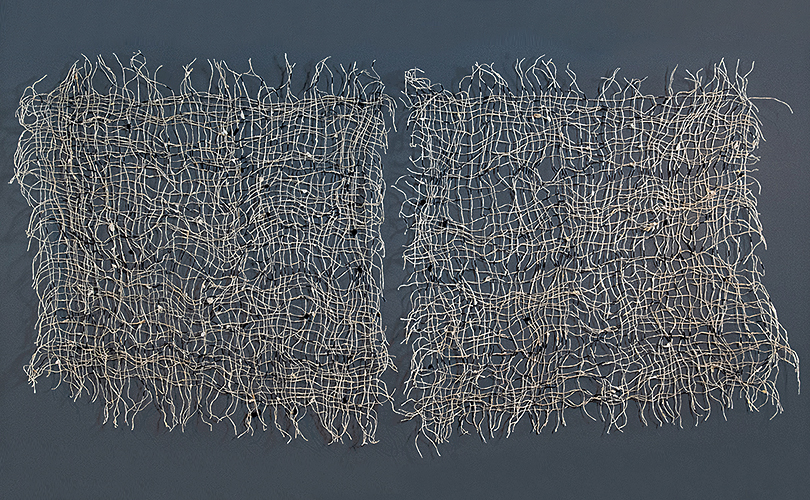

Iwata has made objects of kibiso and also grid-like tapestries which Adams described as apearing as fragments,… “there is an unfinished quality to them,” she writes. “Some are large and freeform, while others are intimate and marked off by a frame.” According to Iwata, the “complex nuance of North versus South” has influenced her work since she re-crossed the Mason-Dixon line. It’s been in the last decade, I that she has transformed woven kibiso made into tapestry-like hangings. “They are either dyed or embellished with gold leaf,” she explains, “and I enjoy the process as much as the results. The whole idea of working, using hands and mind, and letting the process lead me is an eternal moment of joy for me. Sometimes I use a frame to give the piece a limitation, and other times I let the wall space frame the piece. It really is a difference in how I like to present the piece.” In Iwata’s hands, kibiso leads to striking results.