FOR THE LOVE OF CLAY

by Kim Schuefftan

Yasuo Terada and his son Teppie with Carol in front of their 14 chamber noborigama which they are currently building in Seto.Looking down from the top of the 14 chamber noborigama kiln of Yasuo and Teppie Terada. photo by Richard Selfridge

In a recent television foray into the art world of New York, a young artist declared that he does not have to get involved with ”tedious craftsmanship.” Well good for him. Who likes to do drudgery or mechanical labor? For an artist, what could be better than to avoid all the messy preliminaries and snuggle right into the final act of creative fulfillment? All the materials that one could possibly desire to make anything—highly refined and without impurities—are available in stores or from mail-order places, thus freeing the artist to go about the essential business of artistry. Or so many people say.

The boast of not having to be fettered to “tedious craftsmanship” contains a number of assumptions: craftsmanship is not artistry; craftsmanship is sterile, boring drudgery; it is a millstone about the neck of self-expression; it brings no rewards of personal gratification and is to be avoided.

It is not too dangerous to assume that everyone knows that pottery is make of clay (“pottery” here is used to mean the same as that clumsier plural word “ceramics”), and that this clay is made into shapes and hardened somehow with heat. Pottery also has colored surface decorations of various kinds, some shiny, some not.

So what is clay? For many North American studio potters, clay is something that comes in large wet lumps wrapped in plastic, pretty much ready to work. For commercial potters, clay is various kinds of commercially milled powders with odd names sold in 100-lb bags; these are mixed with water in secret proportions to make secret clay formula(s).

The difference between clay and ordinary mud is that the particles of clay are extremely fine alumino-silicate crystals; these form a semicoloid in which the crystals are “lubricated” by a film of water and slide over one another to form a sticky, plastic mass. “Primary” clays are formed by decomposition of certain types of rock (basalt, granite, gneiss) and are found near such rocks. “Secondary” clays are primary clays that have been eroded away and mixed with all kinds of mineral and organic garbage. Particle size, amount of impurities, nature of impurities, etc. dictate a clay’s characteristics—plasticity, fusability and refractoriness, texture, and color.

There is a strong tradition in Japan of the potter prospecting for and digging his own clay. This seems very much an anachronism in today’s world of sophisticated processing and refining to produce standardized, pure materials available to all at good prices. Why should anyone tromp about the countryside, digging up and schlepping heavy dirt that can be bought and delivered with a phone call? The number of potters in Japan who have chosen to dig their own clay is very small today, and will get smaller.

Yasuo Terada in a pottery shop in Seto. Richard Selfridge

One such is Yasuo Terada, who works with his two brothers in the pottery center of Seto, outside of Nagoya. Terada and brothers are fourth-generation potters working in the Oribe ware style, in the tradition of everyday restaurant ware (kappo shokki). Terada has something of a name in the Japanese art pottery world. His fame keeps his workshop (with brothers and staff) at a high level of productivity. Yet, he himself goes out and digs all the clay that he uses.

Why? Why should a noted ceramic artist involve himself in “tedious craftsmanship”? Digging up dirt and hauling it about is hardly fun or creative or artistic. Or is it? Terada states that until a few years ago he bought his clay as most Japanese potters do.

The popular image in the U.S. of a potter (male) is of the well-fed-but-hungry-looking artisan happily plopped before a potter’s wheel forming creative forms, with a garden full of herbs and a wife who weaves (and a goat, dog, and barefoot kids). This image has been around for a few decades.

Work on the potter’s wheel represents less than 10 percent of the total energy output in a serious pottery, states Terada. The American happy artist-potter image does not include such things as digging and preparing clay, splitting logs for a wood-fired kiln, and the like.

If asked, Japanese potters in general will emphasize the importance of firing first, then clay, then forming; another common hierarchy of importance is clay first, then firing, then forming. Terada is adamant that for him all three aspects have the same weight and importance.

“Clay involves prospecting for and digging the material, testing and analyzing it, and finding which clay goes with which glaze—all that is clay.

“With firing, one has to design and build a kiln before one can fire it. But, basically one has to find the glazes that fit a given clay, then determine how that clay is to be fired. How it is fired is determined by the design of the kiln. Clay and firing are interlocked.

“Again, a certain clay is best used for certain forms and designs and not for others. Thus, the forming process is also directly related to clay. “

“All three aspects—clay, forming, firing— are closely interwoven and have the same importance, I feel.

“With potters who buy their clay already prepared and who use a commercial gas kiln, the clay and firing have little importance per se. What is left is forming—design and decoration only. This is true today in Japan as well as elsewhere. Of course, interesting things can be done with such heavy focus on forming and design, but….”

The qualities of a clay vary depending on how it is refined. Whether taken as stone from a mountain or dug wet from under paddy fields, clays usually undergo some refining or processing before use. These processes make clay more plastic by allowing the lubricating water film of the semicoloid to coat individual particles rather then aggregates.

As mentioned, each of the clay refining processes does different things to a given clay, and the possibilities of a single clay are thus expanded.

Yasuo Terada says that no two clays are the same, that there are as many clays in Japan as there are people (110,000,000) and that they are all alive.

I accompanied Terada to dig two different clays. Both sites are within ten minutes’ drive of his workshop, but digging clay at both sites is not exactly encouraged—one side is on government land, and bureaucrats get unhappy easily, and the other is on undeveloped private property. Those who dig clay may find that this activity is often done with a certain element of stealth at night.

Prospecting for clay in the wild involves a whole set of skills and instincts. In Seto, where pottery has been made for eight centuries, it is pretty safe to assume that clay is there. One just has to have the right internal radar and the desire to find it. If one looks carefully in the corners and rooms of the Terada workshop, one discovers an astonishingly large number of green plastic sacks, all of which are filled with clays of various kinds, all dug by hand.

The nature of a clay directly affects the kind of decoration used. Light clays allow painted and transparent decoration as well as enamels. Dark clays encourage light slip decoration and colored glaze pours and splashes. Clays that do not take applied glazes well are receptive to kiln effects such as flushes and runs of natural ash glaze from the ash in the wood fuel, scorches and flame marks and flashes, stacking effects, and texturing of the clay with feldspar bits, etc.

Variations in clays result in differences in the final product, like this Cup by Terada Yasuo, who works in Seto and this unglazed vessel by Yasuhisa Kohyama of Shiragaki. Light clays allow painted and transparent decoration as well as enamels. Dark clays encourage light slip decoration, colored glaze pours and splashes. Clays that do not take applied glazes well are receptive to kiln effects such as scorches and flame marks and flashes, stacking effects, and texturing of the clay with feldspar bits, etc. Richard Selfridge

Clays also change according to how they are fired. Gas and electric kilns produce pretty much a standard product with little flavor, leading to using glaze as a kind of paint to hide the clay surface. Wood-burning kilns elicit sensitive changes in a clay body, which will give different effects depending on where it is placed in the kiln. “In a [wood-fired] kiln, every clay has a place that is perfect for it, where it will do what it does best.”

Terada’s fearless devotion to his craft and to clay is perhaps best illustrated by the following event. Toward the end of one of my visits to his workshop, the unthinkable happened—something exploded in a kiln that was just starting to fire. What exploded was a great mass of clay that was meant to be an objet in an exhibition. Terada was mortified—such things happen to amateurs. He had failed to give the large mass enough time to dry thoroughly, and moisture inside expanded to cause the explosion. The kiln interior was shambles. But…the broken chunks of clay were assembled on a blanket, and Terada immediately proceeded to glaze them. They were then refired and assembled as a totally different kind of objet, one that perhaps even more than the original concept expressed something essential about clay. Most potters would have thrown out the whole mess as a failure. Terada had not heard of Richard Long at that time.

One of the important terms in the verbal armament of the Japanese connoisseur of crafts is tsuchi aji—”clay taste.” A pot, a work, is judged on how it captures and conveys the material—the clay—of which it is made. A potter is evaluated on how he has persuaded the essential character of the clay to come forth, to be alive. To achieve this, something closer than intimacy with materials is necessary. Call it love. Any artist who sees craftsmanship as tedium is rather sad. Sure, he or she can make thing with store-bought stuff, and things made in this way may be just fine. For the potter, the act of digging clay epitomizes a total commitment to the craft, to the art. There is no law that says digging clay has to be tedious—it can be an act or worship, an act of love. Foreplay with a shovel, if you will..”

9/27/2010

WASHI – A PLAIN SHEET OF PAPER

by Kim Schuefftan

Paper. The word has little potency. Paper is something cheap and ever-present, produced in inconceivably immense quantities—one of the things that we easily throw away, no matter how recycle conscious we may be.

Washi. People interested in fiber or craft may encounter the word washi, which is usually defined as “Japanese paper” or “Japanese handmade paper,” with the implication that it is somehow something special. Well, it is special, but not as touted by commerce. Today “washi” is most often applied to colorful and decorative papers or to industrially manufactured papers that have a Japanesque or folksy feel. The word has become something of a marketing category, and washi’s simplicity, strength, and honesty have largely been forgotten. Washi is much more than paper with Japanese surface decoration or charming color or quaint, off-white, faux-natural paper. Washi encompasses all the papers made for over a millennium in Japan with great skill, deep knowledge, and intensive labor.

Thousands of Washi

In Japan, as in other papermaking countries until the age of mass-production, paper always had value. It was used carefully and never wasted. The only reason to throw it away was when it was used to its limit, not because there was an unending supply. Still, washi was part of daily life, made by lone farmers or entire villages throughout the country. By 1850, there were thousands of types of washi made in Japan.

Today’s society and economic infrastructure have defined the traditional method of papermaking as an anachronism at worst and nostalgic revival at best. There is no place in today’s world for washi as it was made a century ago except as an expensive luxury item. Traditional washi workshops have had to produce various decorative and novelty papers just to survive economically; people today have little exposure to and appreciation of simple “white” washi. But artists do. Rembrandt is known to have used washi for some of his etchings. Printmakers through the centuries have admired washi’s quality and ink absorbency. A few artists today make poetic and lyric statements using only plain varieties. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi designed his famous Akari line of lighting fixtures around the beauty of washi’s translucency.

Rice Paper??

Papermaking in Japan was a winter activity. It was ideal slack-season work for farmers, and was made throughout the country, wherever there was a good and abundant supply of soft, running water and bast fiber plants. It was a perfect industry for people in a mountainous country with heavy rainfall and short, swift rivers. One person cannot perform every aspect of making paper—it is a true communal craft. And cold is necessary in every phase of the work. By far the most widely used bast fiber plant for traditional Japanese paper is the paper mulberry (kozo); this and two other plants—mitsumata and gampi—are the main materials. (Hemp, bamboo, and various other fibers account for only a tiny percent of the washi made, mainly for special purposes.) Washi in not “rice paper.” This misnomer—a catchall for any paper made in Asia—is a source of confusion and misunderstanding. There is no paper made of rice.

Gampi has the longest history in Japan. Its beige paper has a rich sheen, is finely pored and strong. The gampi plant has resisted cultivation; the wild plants must be harvested in spring, which is the only time that the bark can be peeled from the stems.

Mitsumata paper has a soft surface luster, a gentle reddish tint, and is supple and soft. Its fiber mixes well with gampi and kozo fibers.

Kozo is harvested twice—at the end of autumn and in winter, as is mitsumata. Its sinewy fibers make a wide variety of robust papers. from the finest tissues to thick papers for an equally wide variety of uses. Kozo paper is one of the pillars of traditional Japanese architecture, along with wood, earth, and reeds.

Scoop Shake Shake Toss

Most visitors to a papermaking workshop see only the most spectacular step of the process—the papermaker making sheets of paper by scooping pulp solution onto a screen.

A papermaker’s finely tuned skills are most apparent during the pulp scooping process. Preparation of the pulp solution itself demands much experience, to get the proportions of water, pulp, and mucilage just right.

The viscosity added by the mucilage means that the pulp solution drains slowly through the screen. This allows a longer time to shake the screen in different directions so that the fibers interlock; it also means that there is excess solution on the screen, which is tossed back into the vat. This solution tossing is unique to Japan and is the step of papermaking most loved by photographers. Everywhere else in the world, the pulp solution is allowed to drain through the screen, and the paper is dried directly on the screen. In Japan, the wet sheets are stacked, pressed to remove water, then applied to boards or a heated iron griddle to dry.

Most workshops have adopted the iron griddle. This dries a sheet of paper in a few minutes indoors rather than hours in the sun. The price paid is that fast drying on a hot surface weakens the fibers and makes them flaccid. Natural shrinkage and slow drying in the sun gives each sheet character and soul. Such things are almost impossible to describe in words alone, but become obvious when a sun-dried and iron griddle-dried sheet are felt and compared.

GROUNDWATER by Mutsumi Iwasaki, plaited handmade Japanese paper, paper string persimmon tanin, India ink, 10.5″ x 6.25″ x 6″

Simple and Humble

Most aspects of traditional Japanese papermaking are totally at odds with today’s economic infrastructure. Understanding the labor-intensive steps of traditional Japanese papermaking enriches the appreciation of washi’s value and beauty.

Nothing could be more simple and unassertive than a plain piece of paper. A simple sheet of handmade paper is an object of great beauty. The intensity and quality of labor that go into each sheet, as well as the quality of materials, create this beauty. Author Sukey Hughes, in her Washi, The World of Japanese Paper, states that if one looks at good washi, “…one begins to see that it is not only its physical beauty that one understands but that one can also get to feel the whole of it, to know the labor behind its birth and the simple dignity of its evolvement.…” This, she affirms, is “…a beauty that makes an artist of the viewer.”

The tea ceremony has a phrase “ichi go, ichi e,” which has both spiritual and very practical meanings. In general it means something like “being in the moment,” or “living this moment to the fullest,” or “meeting the world fully.” This is basic to traditional papermaking. Devotion to craft, skill, and the letting go—allowing materials be themselves fully, without compromise—are what give handmade paper its beauty and quality. Hughes observes, “Each papermaker must constantly go through the initiation of essential meaning in his labor. Every time he makes paper he is the first man to make paper, and every new sheet is his first sheet.”

9/19/2010

PUBLIC ART

HOW IMPORTANT IS PUBLIC AND APPROXIMATELY VICE VERSA

by Kim Schuefftan

Public Art is a something that all who live in Japan have intimately experienced, whether they are conscious of it or not. Japanese public art runs from sprigs of day-glo pink plastic cherry blossoms festooning shopping streets to a Masayuki Nagare marble defining the majesty of a Tokyo high-rise. (Granted, the former is not yet considered Art….) Lots of variety, depth, and scope.

Foreign visitors sometimes wax manic about the quality (or is it quantity) of public art they encounter in this country. It would indeed be interesting to know if and how Tokyo (and Japan) rank with other cities (and countries) in the virtues of public art.

What people see, of course, are usually the well-placed, official pieces; less ambitious and grassroots objects tend to get overlooked. This is clearly because most official public art does not catch the eye unawares, so to speak, as bombard one with its own importance and the importance of the building(s) of which it is an adjunct. Such public art has all the subtle nuance and gentle innuendo of a major meteor strike.

Public art as we know it started long before Japan’s bubble economy was at full froth. (The bronze Family Group or demure nude found in the center of those grassy circles fronting stations everywhere are public art, but such pieces are of the official-neutral, not the official-look-at-me-I’m-important, persuasion, and don’t count.)

Perhaps it was the optimism of an expanding economy, or perhaps nothing more than clever publicity—whatever the cause, in the 1970s a few new corporate buildings in Japan got born together with a piece of art—twins, if you will.

How those construction budgets ever got to include the vast chunk of money needed for Art probably involves melodrama in the heart of executive Oz. Fortunately, we might never know how this happened.

What we must remain thankful for is that somewhere back in the 1970s, when corporate and municipal architecture in Japan still aspired to the aesthetic perfection of the cabbage crate (and, largely, still does), here and there sculptural objects began to appear in conjunction with such public buildings. Love them or hate ‘em, at least one could relate to the sculptures, which was and is not always possible with the buildings they decorate. Those first public art works were generally lumps of various kinds and degrees of grace. Somehow SOLIDITY was the keynote, as if the expense for art had to be justified by making it appear unquestionablypermanent.

Once public art was in, modes and marketplace permuted quickly. Lumps were supplanted by other expressions—great, wind-flung chrome mobiles and pieces of lighter construction, for example.

Today, twisty-twirly metal things that rotate and contain a hiccup or two are popular before facades of buildings. Then, belatedly, Japan discovered soft sculpture, and fiber art began to modify stone and concrete surfaces.

Official public art is certainly subject to the permutations of fancy and fashion, politics and pretensions. But there are objects gracing public spaces—or at least on public view—that have appeared “spontaneously” and that arise out of the psyche of the community (or of the country). Such pieces are not official, and may be called public folk art, for want of a better term.

One of the great monuments of this genre disappeared in 1994.

For over twenty years, commuters on the platform of Tokyo’s Takatonobaba Station were given a view of the Primal He dancing a basic sumo with the Archetypical She under a bubble of flowing water. He and She rotated about a central point, the Center of the Universe; each radiating his/her polar essence—yin and yang, etc. etc—unified by their unending movement about the navel of the cosmos. At first they were both nude, then someone, perhaps a member of a local women’s club, painted a black mawashi (sumo wrestler’s loincloth) on Him, all the more to emphasize his primal masculinity.

Not every city has a Center of the Universe, much less one clearly visible from a station platform. The numerous Statues of Liberty dotting Japan, both in urban and rural venues, do not count. Despite the French conviction that the universe revolves about France, Paris itself does not contain one such nexus. All those monuments and obelisks and the like stuck in the center of large traffic rotaries are simply too blatant to qualify as universal truths. Naivete, directness, and wonder are needed—and an unexpected location. He and She did their unending sumo atop the Suzuya Pawnshop.

Sadly, the dance ended. And I did not notice for months. To celebrate its affluence, Suzuya rebuilt and increased the height of its building, with expensive gray granite facing, and replaced He and She with a bland, pebbly “waterfall.” Suzuya is proud of it; the “waterfall” is terribly nice. It is not the Center of the Universe.

The Center of the Universe changes and moves of its own volition. It uses the genres of public art to make appearances when and how it pleases. If readers discover its new form and location, please let me know.

9/12/2010

WHAT IS AN ART MUSEUM?

by Kim Schuefftan

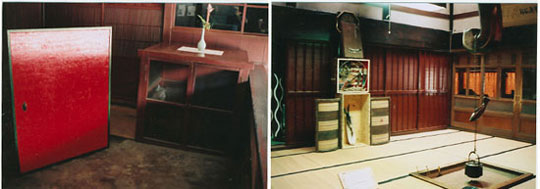

From May 31 to June 9, 1991, the town of Tsurugi near Kanazawa in Ishikawa Prefecture was the venue for an exhibition of contemporary Japanese art — the whole town played host, and the old buildings housed the various works. This concept was a first for Japan, and was organized and put together by people in the town and the nearby city of Kanazawa in only three months.

This concept and event had a strong life of its own. The idea of displaying “new” art works in “traditional” settings is clever and interesting and seems to have been done in Europe over the years, but the result here was something quite fundamental and unexpected—and much larger than a mere cleverly conceived art show.

Hmmm…. How to say this.

All of these were seen, not just automatically dismissed as everyday, familiar, and not worth notice, like we usually do.

9/05/2010