Textiles and Politics

by Carol Westfall

“Life has become significantly more political in the new millennium, especially in the aftermath of worldwide financial crisis. Art is both driving and documenting this upheaval. Increasingly, new visual concepts and commentaries are being used to represent and communicate emotionally charged topics, thereby bringing them onto local political and social agendas in a way far more powerful than words alone.” From Art & Agenda: Political Art and Activism, eds. Klanton, Hübner, Bieber, Alonzo and Jansen (Die Gestalten Verlag, Berlin, 2011).

Textile art is no exception to the rule that art both drives and documents political upheaval. In the 60s, 70s and 80s, issues of feminine empowerment were regularly depicted in art textiles by Judy Chicago, Miriam Shapiro and others. This post looks not at that body of work, however, but at the textile in relationship to other national and international political issues, including war and peace, population control, energy and natural resources use and economic inequality through the arpilleras of Chile, the works of several other artists working in textiles, and my own work, which over the years, has become much more politically inspired in response to current events.

Encadenamiento. Enchainment by Gaia Torres. Protesters would chain themselves to the gates of Congress demanding information about their missing or imprisoned loved ones. From: Chilean Arpilleras: A chapter of history written on cloth, Margaret Snook.

Arpilleras are vibrantly colorful appliquéd traditional Chilean textiles that were used in the 1970s to illustrate the brutality of life under dictatorship. Marjorie Agosin’s Tapestries of Hope, Threads of Love: The Arpillera Movement in Chile (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., New York, 2008) chronicles the plight of the penniless peoples in Santiago after the installation of General Augusto Pinochet as dictator. American and other foreign owners of the copper mines in Chile did not want to see their companies nationalized. The CIA, under the direction of President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger stepped in to initiate the end of the duly elected presidency of Salvador Allende. Eleven hundred Chileans simply disappeared, and to this day, their grieving families have received no word as to their whereabouts and whether they are alive or dead. Most of the “disappeared” were either the sole or partial breadwinners for their families and it became incumbent on the women who remained to continue the search for the missing person(s) and to provide the means to support the family – thus the beginnings of the making of the arpilleras. Under the benevolent watch of the Catholic Church, groups of women would meet to create the arpilleras with the materials they had found or that were given to them by the church, which also provided the workroom space for the creation of the tapestries. A large pot of soup was provided for those who needed food. The idea of safety and sustenance, both spiritual and physical, was paramount within the interior rooms of the church. The actual making of the textiles provided a path to wellness for many of the women. The Catalogue of Chilean Arpilleras, curated by Roberta Bacic, of arpilleras exhibited at the Harbour Museum, Derry, Ireland in 2008, describes the political content of these works: “In the arpilleras are elements such as photos, images, and names of the missing and sewn words and expressions such as “¿Donde están?” (Where are they?) The tapestries often have a “relief” quality and are more than two-dimensional pictures.

¿Donde Están? Where are they? by Violeta Morales. Families place black & white photos of missing loved ones on placards held high. Photos were an important symbol in that they attested to the lives of those who the government denied existed. From: Chilean Arpilleras: A chapter of history written on cloth, Margaret Snook.

The scrap material and stitching that ultimately create the simple and clear lines and forms of the figures and motifs depicted allow the viewer to perceive the determination of the Chilean craft women. They have served as testimony to the tenacity and strength of these Chilean women in their determined struggle for truth and justice and to break the code of silence imposed upon them and upon the country. At the time they were done they depicted what was actually happening, today they are witnesses to what cannot be forgotten and is part of our present past that needs to be dealt with.” Catalogue of Chilean Arpilleras, page 2.

Concerns about war animate Compound, a recent work by Norma Minkowitz that was featured in Stimulus: art and Its Inception, a 2011 exhibition at browngrotta arts, in Wilton, Connecticut.

Compound is a large panel that chronicles a nightmare scenario, the last moments of Osama Bin Laden’s life. It features a tiny-mesh crocheted surface with what appears – at least in the choice of color – an innocent Paul Klee-like image. It has a powerful push me/pull me effect once the subject matter– which includes stylized soldiers, a helicopter, the compound where Bin Laden was hiding, and the World Trade Center — clarifies itself. This whole is an unforgettable image.

The war in Iraq influenced Dona Anderson, as well and resulted in a series of “armor” pieces. Anderson’s granddaughter was in the army stationed in Japan while the granddaughter’s husband was in Iraq. When he came home for a break, he said he did not have any body armor. Anderson was so bothered by this information that she used her art to create some stylized armor for him.

El Salvador, Ed Rossbach, muslin, camouflage netting, sticks, plastic, plastic tape, wire, tied, dyed, linoleum block printed, 1984, photo by Tom Grotta

A previous conflict in Latin America led to the creation of a textile construction by Ed Rossbach. Rossbach has had a singular and unsurpassed career in the field of the art fabric as both artist and educator. Here, the artist using very simple materials, constructed a powerful anti-war statement entitled El Salvador. The death squads in El Salvador killed many thousands of people before the civil war ended. Gyongy Laky, a student of Rossbach’s, regularly addresses political issues in her work. Laky is a powerful advocate for the environment as well as a proponent of the hiring of more women at the University of California, Davis where the artist taught for many years. An example is the free-standing word sculpture, Slowly composed of letters that can be read as LAG or GAL. “In creating Slowly, I was motivated by my efforts on gender equity in faculty hiring. My word, “LAG,” even headlined in a New York Times article about the problem, quoting me and others, that ran a month before my retirement from UC Davis, “University of California System Said to Lag in Hiring Women,” by Tamar Lewin (May 18, 2005). My colleagues and I statewide, working with the legislature, had turned around the downwardly spiraling hiring trend, but succeeded in only raising the numbers to pre-1996 levels. Gals still lag. There is much more work to be done to eliminate discrimination in faculty hiring. I will be happier when women no longer lag in participation in our society nor in pay they receive for the work they do.”

GLOBALIZATION IV: COLLATERAL DAMAGE, Gyöngy Laky, ash, commercial wood, paint, blue concrete bullets, 2005, photo by Tom Grotta

Through Globalization IV Collateral Damage, Laky also speaks with great force and conviction – this time about the utter, useless waste of blood and treasure that is war. Constructed of ash and commercial wood scraps the three letters spell WAR but can also be rearranged to create other vivid elucidations of the subject: MAR, ARM, RAW, and RAM. Bullets for building and red paint are also used in the construction to dramatic effect.

Felt Balls for Peace, Carol Westfall, felted wool with barbed wire, 3″ each, 1994, photo by D. James Dee

My own life has been marked by war and it is no surprise that my past would be revealed in my art. My Dad fought in the Pacific during the Second World War. My high school friends fought in the Korean War and those who returned joined me as freshmen in college. My first husband served in Vietnam and various acquaintances in my hometown of Jersey City, New Jersey, have served in the first Gulf War and some now serve in Afghanistan and Iraq. In the early 90s, a Dutch artist/curator invited my students and me to join an international group of felt makers to create colorful felt balls for peace to be sold at the Tilburg Textile Museum gift shop. I sent mine to them encased in barbed wire. At age 4, I was so frightened by the nightly radio broadcasts about World War II that I grabbed a couple of pillows and dove under the bed in order to be safe if the Germans began to bomb Williamsburg, Virginia. Growing older, I became more circumspect about my behavior and during the Korean War I rarely sought comfort in a cloth.

Vietnam was another story. Each evening I was alone in my little kitchen in Baltimore, Maryland. (My two children enjoyed time with Daddy while I did the dishes.) Armed with my dishtowels, I fought many very pithy, mostly verbal, but ultimately losing, battles with the likes of Spiro Agnew, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. I broke my share of dishes but felt much better in the process for not only did I clean my kitchen but my psyche as well. At that time I had no idea that Kissinger and Nixon were involved in the coup in Chile, but there were troubling reports that some of our POWs were being deliberately left behind in Vietnam to delay the peace talks being held in Paris. What I didn’t yet understand was how deeply I needed to be able to feel hope for the future, a very different kind of future. Perhaps it was having the children; for I certainly wanted a better world for them than the one I had grown up in especially in terms of American foreign policies. Why did I feel responsible for all the problems of the world? It was much later and at a time of great personal stress that I began to realize that Americans were not always told the truth about political situations. When we became aware of the various government and media lies and prevarications, many of us developed a cynical attitude towards the people and problems facing the country. I spent 35 years of my life in academia. Once tenured, the ups and downs of life outside, barely affected many of us. We were responsible for particular programs and the students whose majors were affected by those programs. Beyond that, real life hardly impinged on our rarified existence. There was a very small group, where I taught who rejoiced every time Israel won a war or battle. They would hold a party in the faculty lounge. My friends in Oslo told me that a variation occurred in Norway on 9/11. The Norwegian Palestinians threw enormous parties in celebration of the destruction of the World Trade Center.

THE PALESTINIANS, Carol Westfall, five keffiyeh, black diaper pins, rocks, 2007, photo by D. James Dee

Like many of my fellow Americans, I knew little of the Palestinian situation. After 9/11, I began to do some reading to try to understand one of the putative underlying causes of the attack; this reading included Edward Said’s From Oslo to Iraq and the Road Map and Perceptions of Palestine by Kathleen Christison. The Palestinians, created in 2007, is the work I did after I had done some reading and research. Later, I became quite interested in the Belgian artist, Francis Alÿs who walked along the borders of Palestine with a paint can dripping steadily to mark the path of the armistice border, known as “the green line,” penciled on a map by Moshe Dayan at the end of the war between Israel and Jordan in 1948.

War is often a substitute for some other, often-hidden agenda. As an artist, I have tried to use my training to to raise people’s awareness of the culture, mores and basic humanity of ‘the other’. I do not profess to understand all that transpires between nations and peoples but the basic concept behind the Casus Belli series is the continuing need for massive amounts of oil.

THE CAUSE OF TOMORROW, Carol Westfall, shibori and indigo-dyed Korean ramie, 2010, photo by D. James Dee

Constructed of felt, small black jihad masks form the structures on the three panels. The Jihad series actually followed the Casus Belli felt panels. Acrylic on fine paper is the medium and the imagery uses the symbols of the Muslim jihad to form the tile patterning – crescent moon, pineapple grenades, bullets, oil wells. The Cause of Tomorrow is a large shibori and indigo-dyed Korean ramie panel with acrylic painted drones of various types crowding the sky. This is a predictive statement that the U.S.’s use of drones will undoubtedly create more terrorists and cause (yet again) future blowback against our interests. When we speak of cloth and politics, flags come immediately to mind. The flag can be used in lieu of other tangible objects to make a point. For instance, burning a flag can indicate anger, hate, disgust or distress. One can use a flag to signal as in the maritime semaphore; here I show you my handmade paper bibs with maritime flags, which spell out What Future?

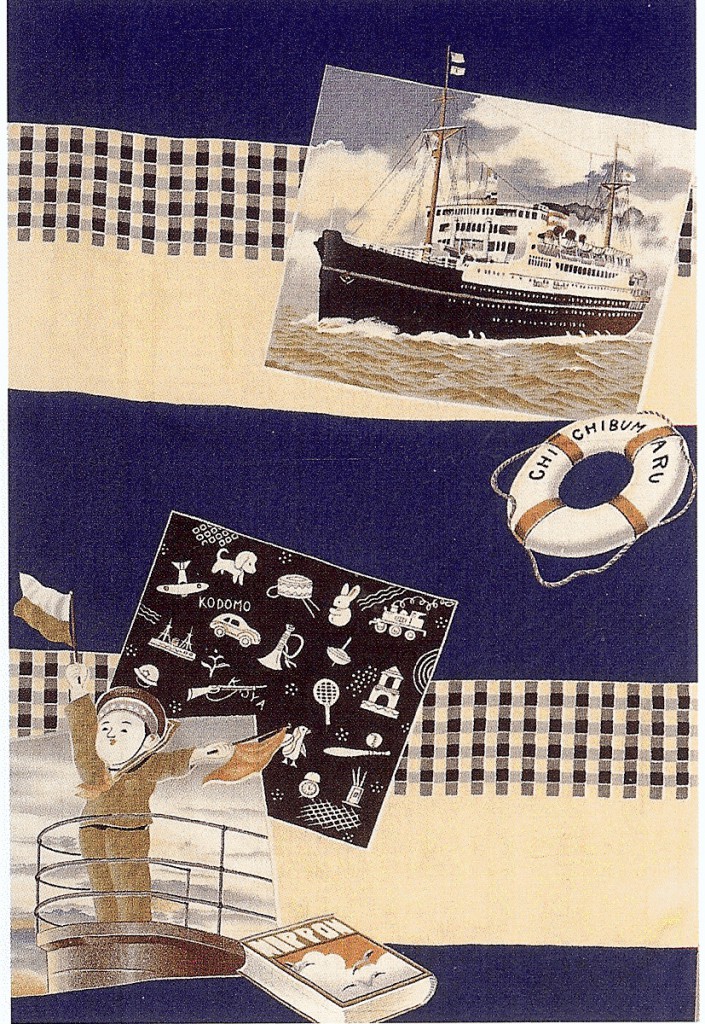

Kimono or nagajuban fabric (detail), “Boy Signaling.” Japan, late 1930s – early 1940s. Printed wool muslin. Private collection. Courtesy of Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture; NY. Photo by Bruce White

In World War II, flags were used to send messages and that practice became the motif for a Japanese textile design with a boy using the maritime flags to send a message. The family of a deceased veteran receiving a flag as a gift from the government of the country for which he/she was fighting, like the Remember Pearl Harbor flag is emblematic. I have made three flags as part of my artistic practice. The first was the Bleeding Flag made during the Vietnam War.

The second was the Clinton flag – popcorn, softballs and little red corvettes from 1998; in hindsight, the Clinton years seem to have been a really good period for most of us.

The Bush Flag of 2003 is quite different in tone and consists of oil cans, fire, smoke, mayhem and violence.

More recently, UK artist Michael Brennand-Wood re-imagined the British Union Jack to make a similar statement about current conflicts, in his 2011 work, A Flag of Convenience – The Sky is Crying.

A FLAG OF CONVENIENCE -THE SKY IS CRYING, Michael Brennand-Wood,Embroidery, fabric, acrylic, toy soldiers, thread, resin on wood base,2011, photo by Peter Mennim

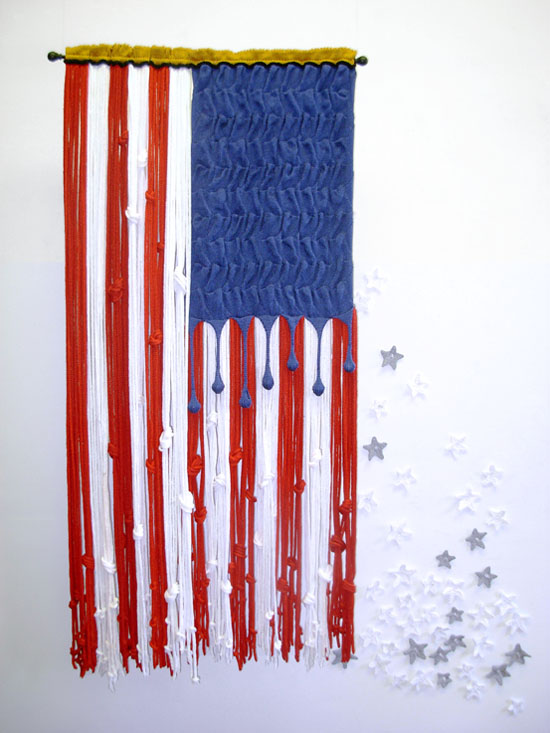

Current issues of economic inequality and political paralysis have inspired further reinventions of the flag. Adbuster’s Corporate Flag uses the logos of businesses as the field of stars and has become the flag of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Massachusetts artist, Adrienne Sloan recently created a flag fiber sculpture to inaugurate a project entitled ”Lobby Congress with Art.” Her flag is featured on a postcard that she urges people to send to their Congressman. (http://www.adrienne sloane.com/ to send one.)

Ms. Sloan concerns herself with the inability of the present Congress to achieve anything due to the powerful partisan politics in both houses. At a perilous time in mankind’s existence on this planet, the issues of ecology, over population, war and more war, we have very little time to waste in affecting meaningful change.

I began to speak out about the environment with my art in 1972 with ZPG, Please (Zero Population Growth) and more recently, I created the Crowded Planet series about the over population issues on this planet.

Artist Judy Mulford, has addressed this theme, too, in her work, Plan Your Parenthood/Overpopulation, which was featured in the Stimulus Exhibition, in which beaded babies burst from every room and even the roof of the tall thin house she has built and embellished with wooden dollhouse chairs, a knitting needle and a rock.

More recently, and perhaps somewhat belatedly, I have spoken out about the increasing need to restrain our overuse of water with the Cascade series. Now I am at work on the Gulf Blues series of 12 panels focusing on the environmental damage caused by the offshore drilling and our insatiable need for oil. As an 11-year old, I lived on Grand Isle, Louisiana, which I remember was like a Biblical Eden. The oil rigs were coming but they were few in number and more ecologically conscious. We left Grand Isle when the Truman Administration gave the tidelands to the Navy. Now, I am following the continuing efforts of BP to cover up the fact that its site in the Gulf continues to leak oil. BP’s environmental track record in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska leaves much to be desired. Politics will continue to play a role in my art.

CASCADE, multi-colored layers of polyester fabrics, metallic threads, Carol Westfall, 2010, photo by D. James Dee

My personal evolution of concern and my study and understanding of other politically inspired artists and cultures convinces me that artists, including me, have a key role to play in resisting the rapaciousness and stupidity of corporations and governments and in helping to create a more humane and sustainable world. As Harold Schenker has observed: ”…artists do have a role to play in society – to provoke. Provoke emotions, provoke thought, provoke dispute… the artist puts him or herself in a dialogue with the collective, often in conflict. As a member of the civil society, the artist can offer a corrective to developments within the collective.”

Crafting Modernism

Carol D. Westfall

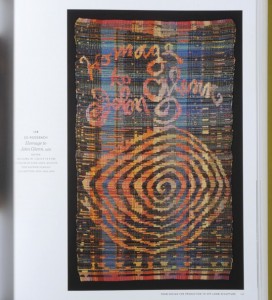

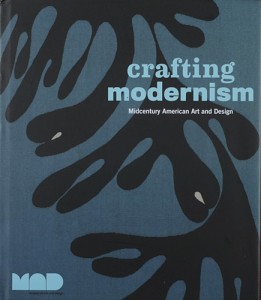

Marks Made by Man and Called Art, Craft and Design Crafting Modernism: Midcentury American Art and Design, at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City through January 15, 2012, celebrates the attitude and can-do spirit of the Whole Earth Catalog published between 1968 and 1972. The current Do-It-Yourself (“DIY”) movement reprises the wondrous seminal work of that publication. Nothing is beyond one’s innate abilities. Just follow the directions and you, too, can build your own ecologically viable home, bake a cake from scratch, plant a vegetable garden with reasonable edible success, sew an outfit that not only fits you but suits you as well! No wonder Steve Jobs described these Catalogs as “like Google in paperback form.” They foster such an independent way of living and thinking and being — nothing is impossible and what might seem impossible just takes a bit more time.

The Crafting Modernism exhibition spans a roughly 30-year period from 1940 through 1970 with lots of pieces erupting at the end of World War II. Intriguing and useful interactive touch screens, which display that timeline, are located on the 4th and 5th floors of MAD. Year by year, selected exhibition art objects are seen in relation to contemporaneous happenings in World Events, Pop Culture, Art and Cultural Events. The screen can be viewed from the MAD website at http://madmuseum.org. (Have fun playing with it!) I confess to spending an inordinate amount of time with this wonderful wall of information and clicking on every image to enlarge it. Take 1946: Russell Wright constructed an elaborate centerpiece bowl with a darkened center and overlapping petals at the sides. The Iron Curtain fell across Eastern Europe and two Frenchmen invented the bikini and named it after the atoll in the Pacific where nuclear testing was taking place. Another event of note in 1946 was a sizeable exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art featuring handmade jewelry – the first to treat it as a modern art form.

Through this digital presentation, the viewer understands that much of history – in this case, American craft, is immensely affected by an apparently unrelated event in a different sphere, like, for example, the passage of the GI Bill. Prior to the end of the second World War, most college art departments were traditional in terms of what they offered as art majors: painting, printmaking, sculpture, art education, etc. In 2005 or 2006, I accompanied a student to Yale to look into graduate art programs and at that time, students could enter painting or printmaking and every other art student went into sculpture – if their interest was in film, photo, video, etc. – they went into sculpture. Once the GIs began coming home and going to school in the late 40s and early 50s, they wanted more options – especially something like silversmithing or pottery from which they could expect to earn a decent living. Although Yale did not add these craft courses as majors, many state-supported schools did. Across the country, these courses opened for many students who, after being trained, went out to set up their own programs or build their own studios and businesses.

“Forms: Transcendental” Richard Pousette-Dart, 1950 REQUIRED PHOTO CREDIT: The Simona and Jerome Chazen Collection

Crafting Modernism is the fourth in a series of exhibitions, catalogues and conferences that comprise the Centenary Project. It is also the first of these four exhibitions to be held at the Museum of Art and Design at Columbus Circle. The first three exhibitions, The Ideal Home, Revivals/Diverse Traditions and Craft in the Machine Age, were held at the former American Craft Museum (ACM) between 1993 and 1995. A great many things have changed during the intervening 16 years. Location is certainly one. Earlier, it was wonderful to be able to leave the ACM and cross 53rd Street to the Museum of Modern Art and the Folk Art Museum. Now, the Folk Museum is over near Lincoln Center, the Museum of Art and Design is at Columbus Circle and only MOMA remains on the original site.

Much controversy accompanied the opening of the new Museum of Art and Design and the change of name from the American Craft Museum. At present, the building does foster a totally different feel from the two predecessor buildings that were somehow much more friendly and welcoming. It would not be a stretch to call the former atmosphere, “homey.” I always experienced tremendous curiosity as I ascended the circular staircase anticipating that the work waiting in the galleries would be simply magnificent! The new building has a cool elegance about it but there is also a certain formality that one never felt in the previous building. Of course, a little controversy can be helpful when opening a new art facility like a museum or gallery. People will come to see what all the excitement is about and that curiosity can engender a new, larger audience to expand the regular group. That may be one reason for MAD’s dramatic increase in attendance – by 2009 they’d recorded 500,000 annual visitors, compared to 150,000 annually in its previous incarnation.

Another reason for the increase in attendance is the expanded exhibition offerings that are possible in the new space. Crafting Modernism opens on the 5th floor in a section entitled: The Design Firms. This is a reference to some of the companies that hired the craftsmen and craftswomen or that bought the products of their studios for resale. The Herman Miller Furniture Company put George Nelson’s 1946 bench of primavera, birch and black paint into production. Knoll Associates produced Eszter Haraszty’s Fibra 1950, a silkscreened linen panel that used varicolored heddles as a design motif. This is one of the pieces in the Crafting Modernism exhibition that I would label as timeless in concept, as the design of this fabric still appears fresh and au courant.

The 5th and the 4th floors are divided into sections with titles like Woodworkers, Collaboration with Industry, Crossover in Art, Craft and Design, Craft in Production, The Handmade Look, Craft in the Modern Interior, Religion, Spirituality and Symbolism, etc. in which works exemplifying these themes are exhibited. There are surprises to be uncovered throughout. In one of the sections exhibiting jewelry, for example, I came upon the name, Jay DeFeo. I knew this artist’s work only through a one-ton painting known as The Rose and I wondered whether this could be the same artist. In the back of the catalog, I found a section called Artists and Advocates and there I found the artist and discovered that she did indeed do the one-ton painting. Making small jewelry pieces, like those in the exhibition, was one of the ways Jay DeFeo earned her living. The exhibition curators have addressed their key themes with solid research and have presented their findings with great care. Examples of works that successfully exemplify these subject areas include:

Woodworkers – Bob Stocksdale’s exquisite harewood plate, dated 1940.

Collaboration with Industry – Taj Mahal was the name given to auto fabric, which was sampled for the interior of a 1959 Lincoln.

Craft in Production – Dorothy Liebes created several textile samples in wool, reeds and synthetics from an over-20-year period, 1948-1968.

The Handmade Look – Warren MacKenzie’s two solid stoneware vases from 1959.

Craft in the Modern Interior – George Nakashima created a small walnut table in 1960.

Crossover in Art, Craft and Design – Isamu Noguchi stoneware work entitled Watashi no mae from 1950.

Religion, Spirituality and Symbolism — Robert Sperry created a stoneware sculpture in 1962 entitled, Totem Crying for Lost Memory

The Counterculture – Richard Marquis used glass and cloth to develop the American Acid Capsule with Cloth Container of 1969-70.

Funk Art – J. Fred Wohl created The Good Guys in 1966.

Surrealism and Humor – Wayne Thibaud painted the Big Suckers, a color acquatint in1971.

New Ways of Weaving – In 1968, Ruth Asawa crocheted copper and brass wire to create sculptural forms that rested inside larger shapes.

Craft is Art is Craft – Claus Oldenburg’s Giant BLT was created in vinyl, kapock, fibers, wood and painted wood in 1963.

California Craft – In 1968, Kay Sekimachi, wove Nagano III in nylon monofilament.

Native Voices – Maria Martinez and son, Popovi Da, created the terra cotta Bowl with Feather Design in 1968.

The Crafting Modernism catalog is a major work in itself. Twelve noted writers, including two of the MAD curators, contributed essays to the catalog, enriching the content of each of the issues addressed. A chapter entitled “Craft is Art is Craft” by Jeannine Falino, one of the curators, opened the perennial dialogue regarding what is craft and what is art and whether there a difference. “The most significant development explored in this exhibition is the arrival of the crafted object as an expression of modern art,” she writes. “The new status of craft was not widely acknowledged by the fine arts world, a situation still true today, but the altered relationship was nevertheless made plain by those artists who appropriated craft-based materials and techniques into aspects of postwar art, and by crafts people whose work addressed process, form and content.” Think Isamu Noguchi and Alexander Calder.

The resource list at the rear of the catalog is comprised of 6 sections:

Artist and Advocates

Schools and Workshops

Museums and Professional Associations

Conferences

Manufacturers and Design Firms

Galleries and Retailers

These entries are all related to works of art in the exhibition catalog.

“Bird” Lounge Chair and Ottoman, Arieto (Harry) Bertoia, Knoll International, after 1952 REQUIRED PHOTO CREDIT: Private Collection

Crafting Modernism and the accompanying catalog provide an invaluable lens through which to view current approaches to art. Earlier this month, The New York Times ran an article entitled, “A Return to the Artisan in the Art World,” (http://www.nytimes.com/2011/

12/03/arts/03iht-rartpfeiffer03.

html?emc=eta1 ), describing how young artists are once again being trained and are gravitating toward traditional craft techniques to produce their artwork. This renaissance in craft techniques seems to be another manifestation of the old truism that “everything old is new again.”

If you can’t get to the exhibition in New York City, it travels to the Rochester Memorial Gallery in upstate New York in February. (Crafting Modernism: Midcentury American Art and Design,

February 26–May 20, 2012 (exhibition opening party February 25) in the Grand Gallery, Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester

500 University Ave, Rochester NY

585.276.8900; http://mag.rochester.edu/exhibitions/crafting-modernism.)

December15, 2011

Fiber Futures: Japan’s Textile Pioneers

Carol Westfall

Akio Hamatani (1947-). W-Orbit, 2010. Rayon, indigo; special technique. Diameter approximately 157 in. (400 cm).

EXHIBITION

Fiber Futures: Japan’s Textile Pioneers

Friday, September 16 – Sunday, December 18

Fiber art exhibitions never fail to leave viewers wanting to touch, but generally they are discouraged from doing so. In Fiber Futures: Japan’s Textile Pioneers, the sumptuous feast of fiber art that is the Japan’s Society’s current exhibition, not only is the viewer invited to touch but to actually make bodily contact with the fabric that covers the entrance door. The first room of the exhibition offers the silky touch of Jun’ichi Arai’s works as the viewer slides between the edges of slit fabric. Arai’s second work is hung alone in the center of the room, again with an inviting slit in the center of the piece. In this case, the work consists of two images of a large circle. One side is silver and the other is gold. These works are the product of Arai’s meticulous research into the marriage of metallics and fabrics.

When Fiber Futures opened in Japan, earlier this year it was double the present size. However, simple economics and the size of the galleries at the Japan Society dictated the need for a somewhat-reduced show. This reduction has served to make each of the remaining works look truly magnificent in relationship one to the other. There is no sense of overcrowding as each work has been meticulously hung with adequate room between the pieces.

Kiyomi Iwata, Chrysalis, 2010. Kyomi Iwata, Cadence, 2009. Jun’ichi Arai, Flame-resistant shop curtain, 2005. Installation photo by Richard Goodbody.

In the same gallery where Jun’ichi Arai’s work is hung, Kiyomi Iwata’s elegant gold leaf and silk boxes cascade down one wall while next to them, a recent work in kibiso, a by- product of silk production, marks a new path for this artist to explore.

Brooklyn- and Japan-based artist designer Yuh Okano introduced her three shibori panels and a single work incorporating a multitude of colorful silk and raw wool corsages by citing the five senses as her source of inspiration: sight, sound, taste, touch and smell.

Tomoko Arakawa’s Prayer for Time and Night Path both use the artist’s own technique for twisting stainless steel fiber to create works of great delicacy and precision.

Hitomi Nagai’s technical tour de force is named Birth. Using the waffle-weave structure, the artist has created a work which expresses “new universes through the interplay of light and shadow.”

Shigeo Kubota’s Shape of Red saturates the center of the second “room” with color and form. These sculptural shapes of Kubota’s new works are imbued with the colors of the sun and mimic nature’s effects at dusk and dawn.

Reiko Sudo (1953- ), Fabrication, 2011. Fabricated by Kazuhiro Ueno. White cotton. 130 x 59 in. (330 x 150 cm). Courtesy of the artist.

Reiko Sudo’s tantalizing piece, Fabrication, was produced by designer, Kazuhiro Ueno. Cotton has been twisted and embroidered and finally sewn in different combinations to form a single piece of incredibly complex fabric.

Rei Saito has developed a way of handling wax resist processes so that the paper becomes as soft as velvet and exceedingly strong. SPA! is a dazzling compendium of colorful pages in a magazine format and scale while Dots is an enormous columnar black work with very subtle surface embellishment .

Akiko Kumazawa employed feltmaking to create her Daisy Chain, which is meant to emulate “a woman’s life giving body and breasts”.

Akio Hamatani’s work entitled W-Orbit provided the perfect image with which to publicize this elegant, pluperfect show of Japanese fiber art. Softly draped around an enormous ring, each thread constructs a perfect shape and the inclusion of indigo-dyed threads, light to dark, at both the beginning and end of the work, is a reminder of how subtle most art of this kind truly is. If you blink, you might miss some little treasure hidden in the work.

Machiko Agano’s room is full of her works , shapes filled with mirrored surfaces backed by images of greenery – trees, leaves, grasses, etc. The mirrored surfaces occasionally catch the image of a viewer which makes the audience feel very much an integral part of the piece. This work from 2011 is a major departure for this artist whose early work emanated from the study of weaving and kasuri fabric.

Kazuyo Onoyama has utilized folded polyester to form the lyrical, sunny surface of Orikata. The artist says,”Using thin fabric to develop simple shapes that emphasize layering, shading and texture, I fold the material over and over again as a prayer for happiness, peace, abundance and good health and as an expression of the close relationship that should exist between human life and our natural environment.”

Kinya Koyama’s sculpture is formed of traditional materials such as kozo, silkworm cocoons and material from the hokigusa bush. The piece is entitled Space-Time’s Memory.

Mitsuko Akutsu has recently begun to specialize in computer-assisted Jacquard weaving. The gallery’s signage explains that “…a deep knowledge of Jacquard technology acquired during a recent period of study at Montreal’s Centre for Contemporary Textiles has resulted in a series of works that place more emphasis on the nature of the medium itself.” This is not surprising as the study of jacquard is very intense. The work will become more personal in a short period of time if the artist concentrates on production.

Tetsuo Kusama, Horizon, 2010. Mitsuko Akutsu, Time J-13, edition number 2, 2010. Mitsuko Akutsu, Time J-15, 2009. Installation photo by Richard Goodbody.

Tetsuo Kusama’s Horizon works from 2010 are a superb color study in three separate parts. Kusama actually makes visible the manner in which the works are put together and held in place by various pleating constructions.

Tetsuo Fujimoto’s “machine drawings” become more lyrical every year. In the work in this exhibition, the artist is creating a surface that emulates nature but ends with the soft, undulating curves of a petticoat.

Hisako Sekijima, Ju san’yo no satsu (A Book with Thirteen Leaves), #553, 2009. Hisako Sekijima, Renzoku suru sen (Continuous Lines), #559, 2010. Hisako Sekijima, Kozo o motsu ryo II (Volume That Has Structure II), #546, 2009. Installation photo by Richard Goodbody

Hisako Sekijima is a world-renowned basketmaker. Early in her career, the artist had the opportunity to work in New York City where baskets were being made of everything and anything and the rules were never stringent as to what a basket was. Sekijima took what she needed from this interaction and went her merry way. The three baskets shown in this show are typical Sekijima – perfectly assembled in pristine materials and always moving ahead in terms of pushing the parameters.

Misao Tsubaki creates collaged “canvases” of extraordinary beauty. The artist says of her work: “The colors and shapes reverberate, vibrate and dance in an endlessly expanding space, looking for all the world like birds soaring through the sky or fish swimming in the ocean.”

Emiko Nakano’s Cambodian Letters reflects her interest in places such as Cambodia, Brazil, the United States and the South American Andes, areas that she has been fortunate to visit. Japan is actually a very small country and this culture was, for a very long time, quite cut off from the rest of the world. As a result, many Japanese take it upon themselves to travel as frequently as possible in order to experience the “outside.” Nakano’s letters are printed on old Japanese papers that are cut into strips and then woven The last step in the process, soaking in hot water, creates a denser sense of the many layers of time and memory that went into this work’s making.

Kyoko Ibe’s Airy Sonnet of Blue, is a commissioned work made specifically for this show. The piece is suspended over the waterfall in the main lobby area. Ibe also exhibits a screen from the Hogosho series, which is made entirely of antique papers.

Hideho Tanaka’s work entitled, Vanishing and Emerging, reflects the process of art making as experienced by this artist. Tanaka says, “I’m acutely aware of accidents that actually help me achieve the expression I am striving for, and other accidents that take my work in a completely different direction.”

Fuminori Ono explains that he started making Feel the Wind “by imagining a shifting, changing fall landscape.” Then he let it “spread out toward the cosmos as if carried aloft on the wind.” This piece is so exceedingly rich in color, it almost vibrates.

Hiroko Watanabe’s Red Pulse is a powerful piece, it’s red so feral, that it must have adequate space around it to avoid overpowering any adjacent work. Fortunately, the Japan Society has displayed it with the space it needs.

Atsuko Yoshioka, Gengaku shijuso no konsutorakushon (Construction for a String Quartet), 2009. Installation photo by Richard Goodbody

Atsuko Yoshioka’s work, Construction for a String Quartet, may not be a true musical instrument in any sense of the word , but there is a wondrous flow through these three thickets. Be it simply a visual flow or not, the connection is made and one wants to somehow connect with the individual “thickets.”

Asuko lyanaga’s A Gift from the Sea: Air X invites touch but unlike the work of Arai, the “Do Not Touch” warning is very evident in this piece. Asuko enjoys spending time in Indonesia where the people and their surroundings provide a rich inspiration.

Naomi Kobayashi and Kyoko Kumai requested that their works be hung one above the other. Kumai used thin wire to create a rocky landscape, above which hovers Kobayashi’s delicate paper “halo” creating hallowed ground beneath the sculpture.

Takaaki Tanaka’s Nest Flowers was created by arranging threads tightly in space and then covering these threads with a paper/fiber mixture which, once dried, holds their given shape in space. Combining prepared units, the artist has built a substantial wall of what he refers to as “nests.”

Naoko Serino’s Generating-8 and Generating-12 involve, as the exhibition catalog explains, creating “ambitious, sometimes room sized installations made from unspun jute, woven and set with adhesive over a preformed base that is removed after the drying process to create soft sculptures made out of fiber, light and air.” The exhibition catalog contains images of a second room-sized installation by Serino that was included in the Japanese Fiber Futures exhibition catalog.

Visitors to this exhibition begin by looking at Jun’ichi Arai’s superb, sensuous circles on fabric panels in both silver and gold. They end viewing the work of architect, Dai Fujiwara, whose circular top, which is likened to a Tupperware lid, allows sunlight to shine through the thirteen-foot opening unfiltered, without passing through glass. The building’s unique construction enables it to support a roof with such a large opening even without a central pillar. Traditional boat builders created the earthquake-resistant walls of the Sun House as it is called. These “bending, slanting lines of the interior walls captures the sunlight so there is no need for artificial lighting during the day.”

In the Japan Society’s press materials, Joe Earle, the Director of Galleries, notes that, “These works remind us that important art need not always be about rebellion or subversion. For most of the 30 artists represented here, it is the material that tells them what to do next in the spirit of tariki originally a Buddhist term meaning the ‘power of another.”‘ Earle confronted the craft-versus-art query on another occasion, telling visitors to the exhibition, “If a work of art is interesting, why question the choice of materials?”

The Japan Society has organized a number of educational programs in conjunction with Fiber Futures exhibition. One of these, a panel discussion, “Dissolving Boundaries and Shaping Discourse,” was held on September 17th.

Takaaki Tanaka, Su no hana (Nest Flowers), 2011. Naomi Kobayashi, MA 2000, 2000. Kyoko Kumai, Toki no katachi (The Shape of Time), 2011. Dai Fujiwara, Taiyo no ie (The Sun House), Kanagawa Prefecture; architectural project initiated in 2000. Naoko Serino, Generating-8, 2006. Installation photo by Richard Goodbody.

The panelists included Akira Tatehata who was recently named President of Kyoto City University of Arts and Director of the Museum of Modern Art in Saitama, Japan. Tatehata’s comments focused on several high-profile contemporary artists including Yayoi Kusama, Man Ray, Christo, Lee Ufan, Tetsuo Kawaguchi and El Anatsui. Summing up, Tatehata stated, “Contemporary art and fiber art have no boundaries. One easily segues into another.”

Another panelist was Hiroko Watanabe, Professor Emeritus, Tama Art University, Chairman of the International Textile Network and one of the artists in the exhibition. Watanabe is an incredibly energetic and a moving force behind many textile activities within Japan and internationally. In 2007, Watanabe led the women-only Silk Road group from Nara, Japan to Rome, Italy, visiting 10 countries and holding textile exhibitions and workshops with local groups along the way. Without Watanabe, Fiber Futures would never nave materialized. In referring to the exhibition, Watanabe Hiroko said “the very qualities that are unique to fabric inspire me and my fellow artists to try to move beyond mere technical mastery to create daring and beautiful ‘works of art.'”

Watanabe blamed the Industrial Revolution for creating the art-versus-craft schism in the West. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, for instance, has its own singular section for design and craft, she pointed out. This is where the NUNO fabrics are always hung. The Museum of Arts and Design seems to have abandoned its previous incarnation as the American Craft Museum and is now veering sharply towards design. However, art speaks its own language, a common tongue, encompassing all aspects of design, craft and art. In the late 2Oth century, many art critics criticized design and fine craft objects on the same level as art criticism. The strong craft tradition in Japan is causing a crossover, says Watanabe, which means that increasingly work is recognized not as fiber art but as art, period.

The panel’s moderator, Joe Earle, interjected at this point that some artists were embroidering their painted canvases, thus crossing over from art to craft and back, an approach that is becoming an accepted procedure.

Watanabe concluded with the statement that the spirit of tradition is very powerful in Japan and that beautiful, well-made objects last forever.

The third panelist was, Matilda McQuaid, Deputy Curatorial Director and Head of Textiles, Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. McQuaid has written many books and articles on art, architecture and design, including Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles, Extreme Textiles: Designing for High Performance, and Shigeru Ban: A Paper Arch. Like Watanabe, McQuaid cited the role of tradition in formulating Japanese textiles as very important. She gave specific examples of the co-existence of old and new, the open attitude towards experimentation and updating without a total return to an old method, citing Nuno’s Bubble Pack, Hiroyuki Shindo’s wrapped indigo-dyed balls, Yoshiko Kimura’s printing technique, Yuh Okano’s personalizing the shibori technique, Jorie Johnson’s felt and lacquer works, Michiko Uehara’s silks from Okinawa, Kyoko Kumai’s wire sculptures, Jun’ichi Arai’s and Sheila Hicks‘ stainless steel thread collaboration at Bridgestone in Japan and needle-punching felt with Issey Miyake. Japan’s rich traditions continue to assist these artists’ journeys of experimentation and innovation.

The final panelist was Christy Matson, an Assistant Professor in the Fiber and Material Studies Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Matson presented slides of an interesting body of work. The issue of the combination of sound and woven surface is the prime mover for her. Industrial processes combined with hand techniques and being open to experimentation create the right atmosphere for extraordinary success in altering, adapting and developing the next new textile. No one knows this better than the gifted Japanese artists in Fiber Futures.

In mid-November, the Japan Society presented another program, introduced by Cara McCarty, Curatorial Director of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, entitled “Mastermind in Textile: An Evening with Fujiwara Dai.” Fujiwara explained to the audience that after graduating from Tama University, he joined the Issey Miyake Paris-based Design Team where he oversaw many projects including the A-POC (A Piece of Cloth) project which won the Mainichi Design Award in 2003. In 2008, he started his own practice entitled DAIFUJIWARA and Co. During this short visit to New York City, Dai has been “hunting for color” which he demonstrated through slides. He spent time at various sites throughout the city such as the Hudson River and Central Park where he made painted strips of paper that matched the color he was trying to capture. Textile and architecture share much in terms of the creative process, he observed. Both begin with a clear concept of color, form and function and require the efforts of a well-trained team of experts to actualize the concept from start to finish.

The Japan Society has several other programs planned before the exhibition closes on December 18th, including a three-day after-school workshop for high school students December 13th-15th, taught by Fiber Futures artist, Yuh Okano http://www.japansociety.org/event/after-school-workshop-fiber-futures-japans-textile-pioneers.

Fiber Futures: Japan’s Textile Pioneers remains at the Japan Society Galleries, 333 East 47th Street, New York, New York until December 18, 2011. For more information, visit: http://www.japansociety.org/event/fiber-futures-japans-textile-pioneers or call: 212-832-1155.

November 2011